Small, light and big-hearted, this TVR has a formidable reputation. Now this one is back in the UK we find out if that reputation is justified

Words Adam Towler Photography George F Williams

What began as a subconscious glance to the right has become a two-stage twitch. Look across, oil temp: ‘check’, coolant temp: ‘check’, back to the straight-ahead. Wipe brow. Wrestle some more at the controls. Repeat ad infinitum.

The TVR Griffith is a hot car on a hot day, in both senses of the word. In fact, so hot was the Griffith’s performance at launch that it was marketed as the fastest car in Britain. Even now, nearly 50 years after its rapid gestation and fraught, brief career, it remains an irrepressible force. A so-called Cobra killer, in reference to the Griff’s ability to stitch up one of Carroll Shelby’s V8 roadsters in a straight fight; small, and from unlikely stock, perhaps Mongoose would have been a more apt name?

Griffith chassis 119 is even smaller ‘in the glassfibre’ than it appears in photographs. Getting into the low-slung cabin isn’t graceful for anyone over average height and once in, headroom is at a premium. Frankly, the overall impression is of sitting in a bathtub with a very large and angry engine for company instead of a rubber duck, but although the cockpit is snug the driving position is decent and there’s a useful luggage space behind the seats. To my right and within easy reach is a Hurst shifter exiting from a broad transmission tunnel, its white cue ball and knife-edged lever a classic symbol of American performance motoring, while a small and chunky Mota-Lita steering wheel sprouts from an uncluttered black dashboard typical of a Sixties British sports car. A chrome rear-view mirror juts out from the dash top, although owners in period wouldn’t have had to worry too much about what was behind them, police cars included.

The V8 rouses without much effort and is soon chugging away up front, its industrial tones reverberating out of the fat single tail pipe. Driving the Griffith slowly is relatively easy once I’ve got the knack of the abrupt clutch, although the controls are predictably heavy. It’s already beginning to get quite warm in the cabin, I note, and we’ve only just started.

The crux of the Griffith’s performance is the fact that the V8 has only 864kg to lug around. It’s this simple equation that dominates the entire Griffith driving experience. Right from the off the clues are there, because barely caressing the accelerator pedal sees the car effortlessly accruing speed. Push a bit harder and it’s clear that, much like the Peter-Wheeler era TVRs, this one has a long accelerator pedal travel, perhaps acting as a kind of primitive safety net for the unwary. Satisfied that you really do mean to pull the pin, it then explodes forth with a level of uncontained vigour that has our photographer clutching thin air in the passenger seat, accompanied by the kind of primitive dialogue between us not suitable for a family magazine. As the numbers attest, this is big, big performance on a level associated with serious modern performance cars, but delivered in a wild and completely safety-net-free package. Exciting doesn’t even begin to cover it.

It doesn’t seem to matter what gear I’ve selected, once the pedal has travelled through a broad proportion of its arc I’m riding the wave of torque as if it’s just me and the engine surging forwards, minus the obvious airstream turbulence. When you consider the power- and torque-to-weight ratios it’s hardly surprising, thanks to 314bhp/ton and 363lb ft ton. So even with just four gears in a 50-year-old gearbox, plump historic tyres and a relatively primitive drivetrain, the Griffith scorches off the line; a top speed of 163mph sounds frankly terrifying.

The Griffith was based on the MkIII version of the Grantura, which means the suspension is a fully independent set-up consisting of double wishbones and coil springs, along with a rack-and-pinion steering system – all attributes that made the revised version of this little sports car an advanced bit of kit for its era. As such, the Griffith has a very useful theoretical advantage over the transverse cart-sprung axles of the crude AC Cobra, but the Griffith, certainly in 200 series form, cannot make the most of its specification. On the positive side, the steering is direct with almost no slop around the straight-ahead. Naturally, it weights up significantly with lock applied, but not uncomfortably so, and to begin with I have the sense that this Griffith will be a very wieldy vehicle indeed. It is, as long as the road is smooth; hit a seemingly innocuous looking ridge in the road though, and it’s off in a random direction with a shudder, the same applying to potholes, awkward cambers or anything really that causes a deviation in the road surface. ‘Bump steer’ was a known problem during the development of the 200, and one that Mark Donohue – who by 1965 was head of engineering at Griffith Motor Cars – was well aware of, but was refused the funds to sort. The kickback through the wheel rim is pronounced enough to go way beyond simply relaying the surface of the road: at times it’s more like a wrestling match. It’s a great pity, because a disproportionate amount of time is spent trying to guide the Griff into something approaching a desired trajectory, rather than actually driving where you want the car to go. This frantic barrage of sensations is further amplified by the very short wheelbase, which makes it an alert, twitchy sort of car to drive, and rather unforgiving near the limit.

Meanwhile, the Griff’s cabin has gone from warm, through uncomfortably hot, to roasting. I am experiencing first hand another of the car’s infamous faults when new – that of heat soak from the rumbustious V8 up front. Despite the vain efforts of the fan, the Griffith runs very hot in traffic: at one point we’re caught at some traffic lights and both the photographer and I watch the needles creep ‘round with increasing concern.

As it does so the interior turns into a sauna accompanied by a heady aroma that we decide may be hot glue, but which in any case makes a formidable combination with the heat, the wafting aroma of hot oil and the clearly visible fumes from the exhaust, all rendering us rather light-headed.

Jack Griffith was a Ford dealer on Long Island, New York excited by the performance boom of the early Sixties. As part of his concession he became a Ford Performance retailer and also took on a Shelby Cobra franchise, the latter including the task of collecting the AC Ace bodies from the docks, storing them, and then sending them on to Carroll Shelby in California for conversion.

Hoping to capitalise on the prevailing lust for horsepower, Griffith set about creating a ‘Griffith Sprint’ in his dealership workshops, based on a tuned Ford Falcon saloon, into which had been transplanted the new HiPo version of the Ford 289ci Windsor V8 engine. It was a busy period for Griffith, what with his Cobra racing in club events at the weekends, in time piloted by a young Mark Donohue who would go on to become a racing legend, winning the Indy 500, the Can-Am series and more.

Various accounts surround what happened next, but it’s said that one day in late 1963 Dick Monnich, a local promoter, salesman and SCCA racer, drove a small British sports car into the Griffith workshop. Monnich was the official importer for TVR sports cars in America, and as he and Griffith stared at the diminutive Grantura MkIII the idea of shoehorning in a 289 seemed natural enough.

By November both the Sprint and the new V8 sports coupé prototypes were completed, and Griffith set off for Dearborn, Michigan, for a meeting with Ford top brass to seek official approval. Unbeknown to him, the Mustang was imminent so senior management rejected the Sprint, but the sports car was well received and by March 1964 permission was granted. Over in north-west England, the TVR factory was trying to come to terms with the prospect of building six cars a week instead of the hitherto one or so, but by April the first build of the new ‘TVR Griffith’ was underway in a new factory in Nassau County. In time an eight-man production line would be converting 20 cars a week into Griffiths.

“It has a pugnacious air, no great beauty perhaps, but undeniably attractive and with a real thuggish sense of purpose”

They created a small car with a very big reputation. It could almost be called cute were it not for the functional air vents – always fighting a losing battle – and the wider track over the Grantura. As such it has a pugnacious air, no great beauty perhaps, but undeniably attractive and with a real thuggish sense of purpose. If the contemporary Jaguar E-type was the charismatic kid in the class who dazzled the girls and could do no wrong, the Griffith is a sort of short, stocky Sixties version of Just William, forever waiting outside the headmaster’s door with muddy knees and inky palms, and always victorious in a playground punch-up. No one messes with that Griffith boy.

Although the first three Griffiths built were modified Granturas, the production Griffith featured specific body modifications, including the brazen bonnet hump necessary to clear the V8 engine, the aforementioned additional vents and the tapering downwards of the swage line that slices the top of the rear wheelarch. The chassis frame was strengthened and widened, with the front crossrails moved forwards and the engine mounting rearwards.

Development was very much an ongoing affair once production had already started: for example, early Griffith ownership meant scrupulous metering of electrical power on the owner’s part to avoid a drained battery, as well as all manner of mechanical issues, such as leaking fuel tanks. What the engineering team wanted, and what Monnich was prepared to pay for, weren’t always the same thing. And with Monnich controlling the supply of TVR bodies, Griffith’s hands were tied.

So serious mechanical sympathy, patience and $3995 was what was required for a standard 195bhp Griffith at launch, with the full-house 271bhp HiPo engine option costing an additional $495. In return you got just about the fastest accelerating car on the road, with 0-60mph in around 5.2 seconds. It’s not hard to see why for many enthusiast buyers the attraction was hypnotic.

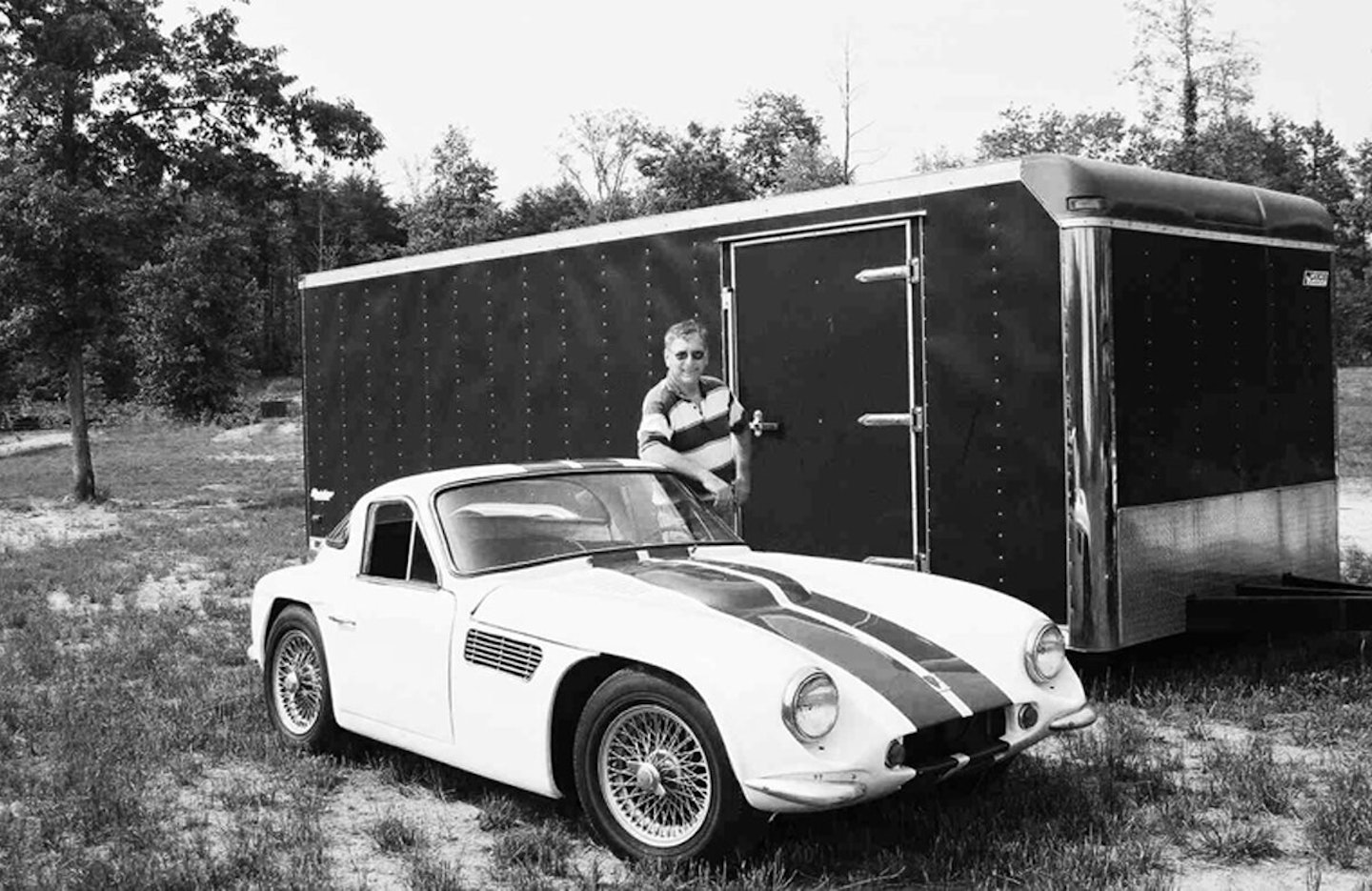

A Mr Stan McDonald in the Chicago area bought this chassis new, the 119th of 190 200 Series models built before the 400 Series arrived. It eventually ended up battered and broken in the Texas sun before moving to Ohio and eventually getting shipped to the UK in 16 boxes. From there it was restored at great cost into racing specification, but the owner felt he’d spent enough and, via a spell on sale at JD Classics, it wound it’s way to Albion Motors in Belgium before being purchased by its present owner, Chris Lowe. He brought it back to the UK and had it turned back into a road car by Neil Garner Engineering. Its condition today is very close to perfection, and it’s believed to be one of only 15 or so early cars presently in the UK.

The Griffith is in so many ways a deeply flawed car. The sadness retrospectively is that most of those flaws could have been rectified quite easily, had Griffith had the time and money to do so. But he didn’t, and moreover there were far greater problems imminent that caused the company’s subsequent collapse. The dream seemed over, but over the successive decades, it became the clear that the V8-powered halcyon for TVR had only just begun.

A test driver’s tale

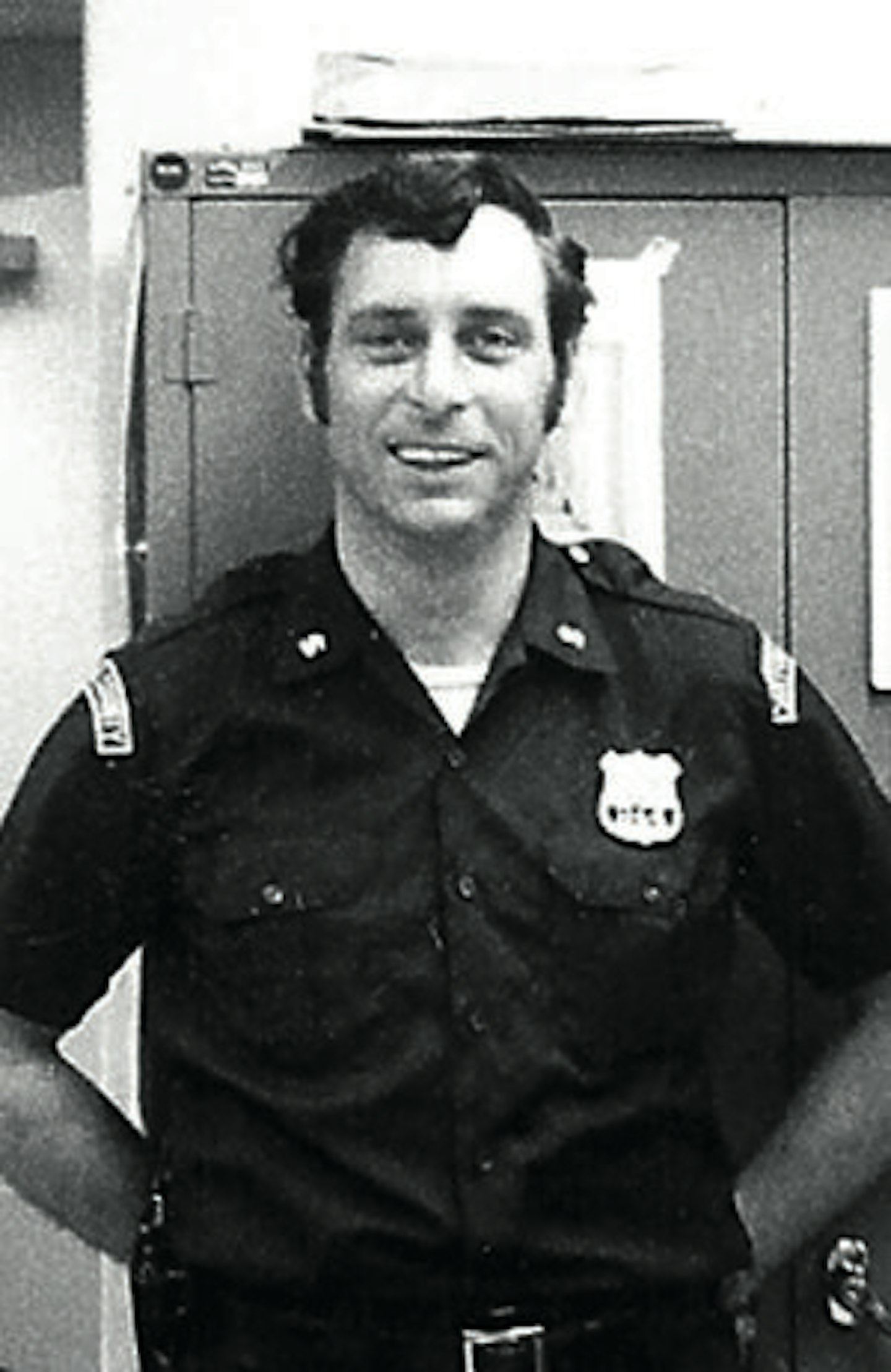

Mike Mooney’s involvement with the TVR Griffith came about through fate. He was a car-mad police officer patrolling the six-lane Long Island Expressway in 1964, when he spotted a small sports car broken down by the side of the road. He recognised it as the same little coupé he’d seen in the workshops of Griffith Ford, the dealer where he’d ordered his own 289 Hi-Po Mustang. As Mooney pulled alongside the driver sheepishly looked across and said, ‘I’ve run out of gas.’ It was Mark Donohue (right).

The young American would-be racing legend was Griffith Motor Company’s chief engineer and test driver. ‘On the drive back we talked cars and I told him I’d been a test driver in the past,’ says Mike (left). ‘He said, “I need someone to give me a good evaluation of these cars but come back with no tickets on the butt”. So for the next year and a half when I wasn’t on duty I’d pick up a couple of keys from Mark and go out on a 14-mile test route.’

Mike is under no illusion that build quality at Griffith could be variable, ‘There were some cars I wouldn’t take over 45mph, but once I did 148mph.’

Mike now owns the Griffith Motor Co name, and is to launch his second self-published book on the cars. ‘It’s funny, if it wasn’t for those leaky fuel tanks I wouldn’t be speaking to you.’