I still find a Countach a strange animal to be around. Even after all that has come after it, including newer creations from the Sant’Agata factory, Lamborghini’s first truly raging bull still has an otherworldly quality. It’s like stepping into a sort of psychic nimbus, wherein all of its symbols and associations clamour around – everything from Bob Wallace’s Italy-to-Monaco prototype dash, through a thousand posters and car magazine features to the favourite choice of bad guys in Miami Vice.

Pulling up the heavy scissor door of this black 1984 car, ducking down and doing a limbo into the leather curve that forms the seat reminds me that everything to do with this machine is a little different; either slightly more mannered or a little harder. Or simply excessive to the point of absurdity. Even in 1984 I remember thinking the extended skirts, wheelarch flares and rear wing were a bit over the top. But this car goes even further. As I sit back and heave the big door down – where is that handle again? – I glance up at the huge, flat windscreen and see another word, equally as potent as the name of this car, emblazoned in bold, square-shouldered script – TURBO.

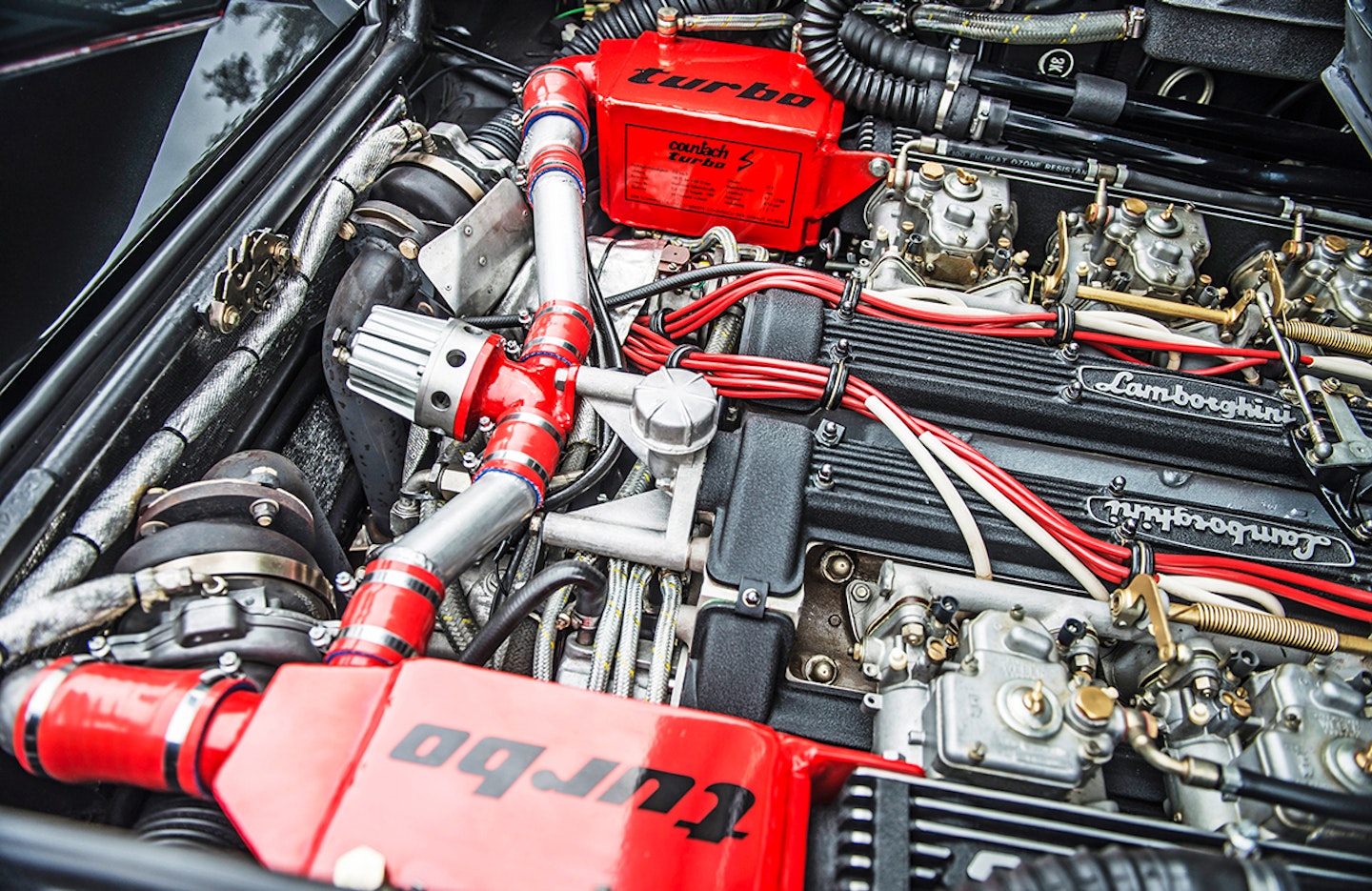

Rising to prominence largely on (or in) the back of Porsche’s 911, the term had, by the Eighties, evolved into a synonym for the fastest, most effective version of just about anything from a graphics card to a food blender. But here, in this Lamborghini, the word retains all of its true potency and meaning. Fitting very snugly behind each cylinder bank of the V12 is a small red box. Each boldly declares itself to be a turbo – both on top and side – and each says, in a kind of boilerplate script, what this car is, when it was built (chassis ELS 12712, 1984 in this case), and that it is indeed the ‘fastest and most powerful Countach built’.

Back in the cockpit, I’m staring at a 425kph speedometer. Below is a boost gauge and, far more worryingly, a stout, knurled, black plastic knob with the word ‘turbo’ on it and two double-ended arrows. I’m not going near that for a while, though the Britax four-point harness, red and yellow against the black leather, suggests I’m going to need to be strapped in tight when I do.

By now I’ve turned the ignition key halfway and the fuel and oil pumps are moaning and ticking, preparing to wake up the big quad-cam V12. By the time this car was produced, the LP400’s 3929cc motor had been bored and stroked out to 4754cc. It still produced 375bhp, but now peak power came at 7000rpm – 1000rpm lower than its predecessor. Torque was higher – 302lb ft, up from 268lb ft at a very accessible 4500rpm. Ironically, Giulio Alfieri, Lamborghini’s technical director since 1978, had dismissed turbocharging as a power option, saying it was ‘only really useful at the top end, while sacrificing the bottom end’.

A quick twist of the key and the engine fires, a starter motor’s whinny followed by a hacking guttural cough and spitting explosions. Cranking up, the Countach V12 sounds like an old Chevy V8 kicked into life after a year slumbering in a barn. A hollow metallic moan rises and falls, although jabbing a Countach’s accelerator isn’t something that can be done delicately. The pedal has more weight behind it than many a hatchback’s clutch. But its resistance and travel are smooth and even. The clutch, too, is quite heavy, though nowhere near as recalcitrant as many have claimed.

First is a dogleg change; the short, stubby gearlever must be pulled in its heavy-duty-looking, open-claw gate left and back, opposite the manually locked-out reverse. It feels easier in a left-hand-drive car, as I pull it in towards my hip. Then that tensed thigh-muscle clutch dip again and click-clack across to second.

As the revs rise, the engine’s metallic soundtrack grows to a hollow yowl that sharpens and intensifies if I maintain the descent of my right foot. Clutch down, off the gas. And then a sound I never thought I’d hear in a Countach – the metallic whiplash whistle of a turbo wastegate clearing.

For a moment, I’d almost forgotten – the sensations so far are all standard Countach – but the hiss normally associated with Nissan Skylines or a Lotus Esprit reminds me of this car’s aspiration. Glancing down at the black knurled knob again, I think it’s safe to say the boost is turned down pretty low. I’m thinking a Countach is a fearsome thing without any power add-ons. So why do it?

It was probably inevitable. Forced induction had allowed the 911 and Esprit to punch way above their weight. Ferrari and Lamborghini were always glancing over their shoulders, trying to second-guess what the other would do next in the quest for more speed and power. The development came at a time when Lamborghini was at its most vulnerable and financially unstable. Although the project was endorsed by the factory, support and facilitation came largely from Max Bobmar, the Swiss distributor, while the engineering was carried out by Austrian tuner and ex-Porsche racer Franz Albert from Wörgl. Albert also worked on Koenig’s equally outlandish bespoke Ferrari specials.

“The mechanical sensuousness of the big Lambo surrounds me; induction roar from six carburettors, exhaust blast... and that punctuating hiss”

His opting for two smaller turbochargers allowed for a greater breadth of power throughout the rev range. However, at full boost the force-fed motor would produce some 748bhp at 5000rpm and a cooling-tower-uprooting 646lb ft at 4000rpm. Dialled back, the car would feel little different from the standard model.

At mundane speeds, like any other Countach it can paradoxically seem to lack feel in the way it engages with the road. Turn the relatively small steering wheel and it simply tracks where you point it, cornering flat. Bumps and potholes are dealt with, without the need to alter my line. The big tyres may follow undulations, but light correction brings the car back. A little more power and it will go round the bend quicker... and flat. I’m using a little more force than in a normal car, but no big deal. It feels like a big endurance racing GT chugging along a pit lane. And like those racers, the Countach’s abilities lie well beyond the everyday. It simply moves through the humdrum world without having to engage even a tenth of its ability. Only when I push more seriously on that stiff right-hand pedal will the Lamborghini’s character and capability begin to manifest itself.

It’s as well the throttle is firm; the car picks up pace in direct relation to its travel without apparently encountering any resistance from any other forces. Early Countaches concentrated more of their thrust at the screechy end of the rev range, but this car pushes smoothly from low down. Moving swiftly through B-road bends, there’s that same indifference – flat, locked down, neutral. Forces have to build up a lot before it shifts its weight and line in any way. The mechanical sensuousness of the big Lambo surrounds me constantly. The clack and snap of the metal-on-metal gearshift, geartrain whine on downchanges, induction roar from six carburettors, camchains reeling through their guides, exhaust blast. All just behind my shoulder blades. And that punctuating hiss.

Within the first few miles I realise the best way to guide it is to maintain a gentle but unyielding firmness, while never snatching at the controls. Everything about it has a resistant, tactile quality and is totally under my command from what at first seems an absurdly reclined driving position. The attitude and profile seem to suggest ‘this is how drivers will drive in the future’. That sense, combined with all the mechanical chatter and the car going quicker and quicker, conjures up a collision of the Countach’s many disparate personas – track car, futuristic concept and glamour wagon.

Once the heady rush is over, replaced by sober reflection, I conclude that I prefer the less fussy and cluttered interior of the old LP400. And as with settling into any Countach, I have to endure the ritual of banging my head, knee or elbow on something or other. In fact, with the style of driving the Countach demands, I don’t want most of the stuff that’s in here. What idiot wants a hi-fi in a car with a twin-turbocharged Italian V12 engine? Or aircon? Or leather? Give me the Countach Turbo Club Sport. Give me more boost.

“The rapidity with which the Turbo digs down and finds the thrust is exhilarating. Suddenly I’m very glad of the skirts and tacky-looking wing keeping it on the floor”

The curves begin to straighten and the tarmac unwinds into a long, level straight. I resist the temptation to floor it, just pushing down smoothly. The engine tone morphs through its whole spectrum in a flash before ending in a chainsaw flourish and that whiplash hiss. Clack, clack, downchange.

The huge back wheels flow the power into the tarmac and the car launches itself forward. I seem to be simultaneously pushed from behind and pulled forward by the steering wheel. Road markings melt into the blacktop and the fields become a watercolour wash. This is what being strapped to the front of the bullet train must be like – it’s the rapidity with which the Turbo digs down and finds the thrust that is simultaneously exhilarating and alarming. Suddenly I’m very glad of all those appendages that are keeping this car on the floor – the skirts and big wing. The car still tracks straight and true, and the firmness of those controls is suddenly very reassuring. At these speeds the Countach becomes alive and almost incandescent with noise as I move the car with small and very considered movements. This kind of acceleration is more standard fare for early 21st century supercars, but back in the mid-Eighties the only machine to pull these kind of stunts was Doc Brown’s DeLorean in Back To The Future.

So, as a hard-driving Gumball type, would I want a Countach Turbo? I’m not sure. Putting a turbo on Porsche’s 911 added a new register to its dynamic range, balance and handling. I’m not convinced we see an added facet to the Countach character by adding the blowers – apart from sheer, hugely impressive acceleration. I also get the feeling that one day I would turn that boost dial too far for too long and the thing would disembowel itself, spitting liquid pistons out of the exhaust pipes.

As a collector? That’s probably a yes. Someone, somewhere had to put all the madness of that era into one car – or a few – and this is a very credible example of those few.