When archivist Gerd Langer found a hand-written reference to a mysterious car forgotten in the Mercedes-Benz storage halls he triggered a huge restoration and reconstruction challenge

The archaeology

Archivist Gerd Langer (left) was trawling the Mercedes museum list number records back in 2006/7 when he came across entry 284. ‘So I went to the storage halls to see what it referred to.’ There, among the 900 vehicles, he found it. ‘It was a great moment – there was a chassis, all piled up together with a rear axle and some other parts.’

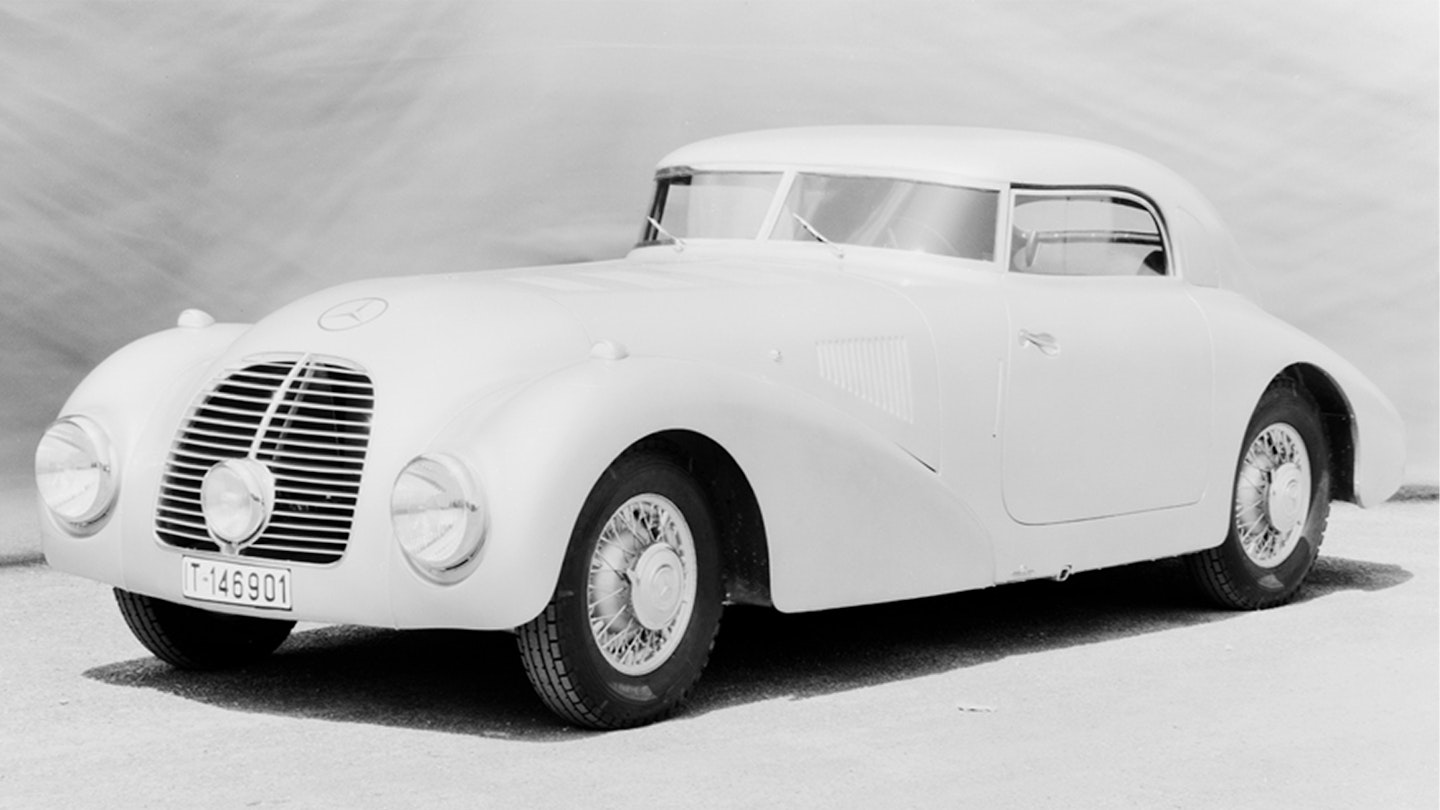

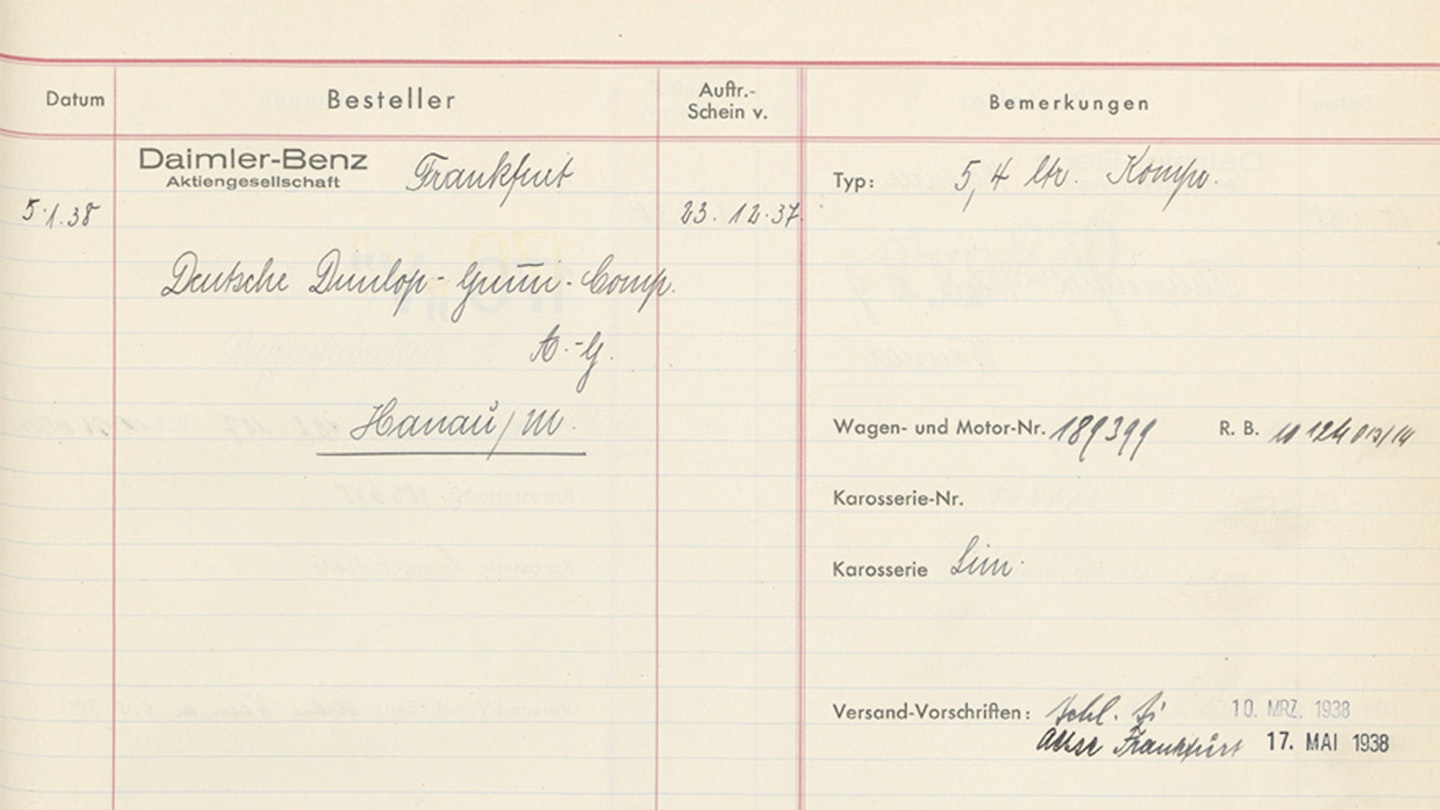

It was clearly a W29 chassis, on which the 540K sports cars were based, but Gerd had no idea how special his discovery was. Fortunately a chassis plate was still clinging to the well-used frame, and its number, 189399, was also stamped directly into the frame. The quest was on. More archive trawling yielded a hand-written entry in the original commission book – a series of vast A3 ledgers listing all the passenger cars built. ‘The number also appeared in the car book and the engine book. It became clear that this was not a normal series car.’ Gradually the archive gave up its secrets, with the official title document showing that the car, registered IT 1346901, was sold to the German arm of Dunlop on June 14, 1938. Dunlop used it for high-speed tyre testing and it was still in use in April 1940, by which time it had been converted to use LPG.

The more Gerd searched, the more exciting the story became. ‘I also found the original design drawing – pen on parchment, the Linienrisszeichnung – a microfiche printout of the original drawings, details of the silver paint and grey leather interior, and six original photographs of the car in a scrapbook of special design projects belonging to in-house stylist Hermann Ahrens.’

What they revealed was a striking streamlined coupé, originally conceived for the stillborn Berlin-Rome race, then repurposed to use its speed and weight to push the limits of Dunlop’s tyres on the autobahnen around Hanau. ‘A number stamped into the rear axle casing revealed a unique ratio of 2.9:1.’ With the supercharged straight-eight running at 3600rpm that would have given a top speed of 185kph (115mph).

After surviving the war in the Dunlop factory the streamliner was used by a US serviceman before it was returned to Mercedes some time during the Fifties. ‘The information was the perfect mix as base for the project.’

Chassis and axle

Ralph Hettich led the project, co-ordinating the work at Mercedes and with specialists all over Europe, but before the technical work could begin every possible detail of the car’s remains and the information in the archives had to be scoured. ‘The biggest challenge was to make it in exactly the right way, not just to look the same. Originality and authenticity are everything, so we had to ensure that the historical traces like the patina weren’t destroyed, while making sure that the functionality was faultless.’

At some point after the car returned to Mercedes in the Fifties the bodywork and most of the mechanical components were removed. ‘Possibly the intention was to rebody the car, but for whatever reason that didn’t happen and it remained here, fortunately.

‘The chassis told us so much about the car. For example, it had special brackets to fit the streamlined body and there were traces of the original silver-bronze paint that was only used on the racing cars. It still had the original fuel pipes, wiring, two of the rear coil springs, bolts for the axle, the brake fluid reservoir and the jack bracket. One of the wheels survived also.

‘The chassis had been heavily used and showed various stains of time, including corrosion and cracks, such as where the steering is mounted. We only used modern welding techniques sensitive enough to repair the cracks without destroying the surrounding material and painted areas. We cleaned the chassis and covered it with a thin layer of wax to so the patina could be seen.’

The rear axle had also survived, complete with its finned drum brakes and the differential unit. ‘We could make out a stamping on the axle casing that showed it had a longer transmission ratio of 2.90:1 rather than the 3.08:1 of the standard 540K.’

An original wheel and pair of coil springs attached to the passenger side provided additional reference for matching the original paint. ‘We didn’t want to re-use them for safety reasons. The wheel now sits in the trunk, unrestored for everyone to see.’

Body reconstruction

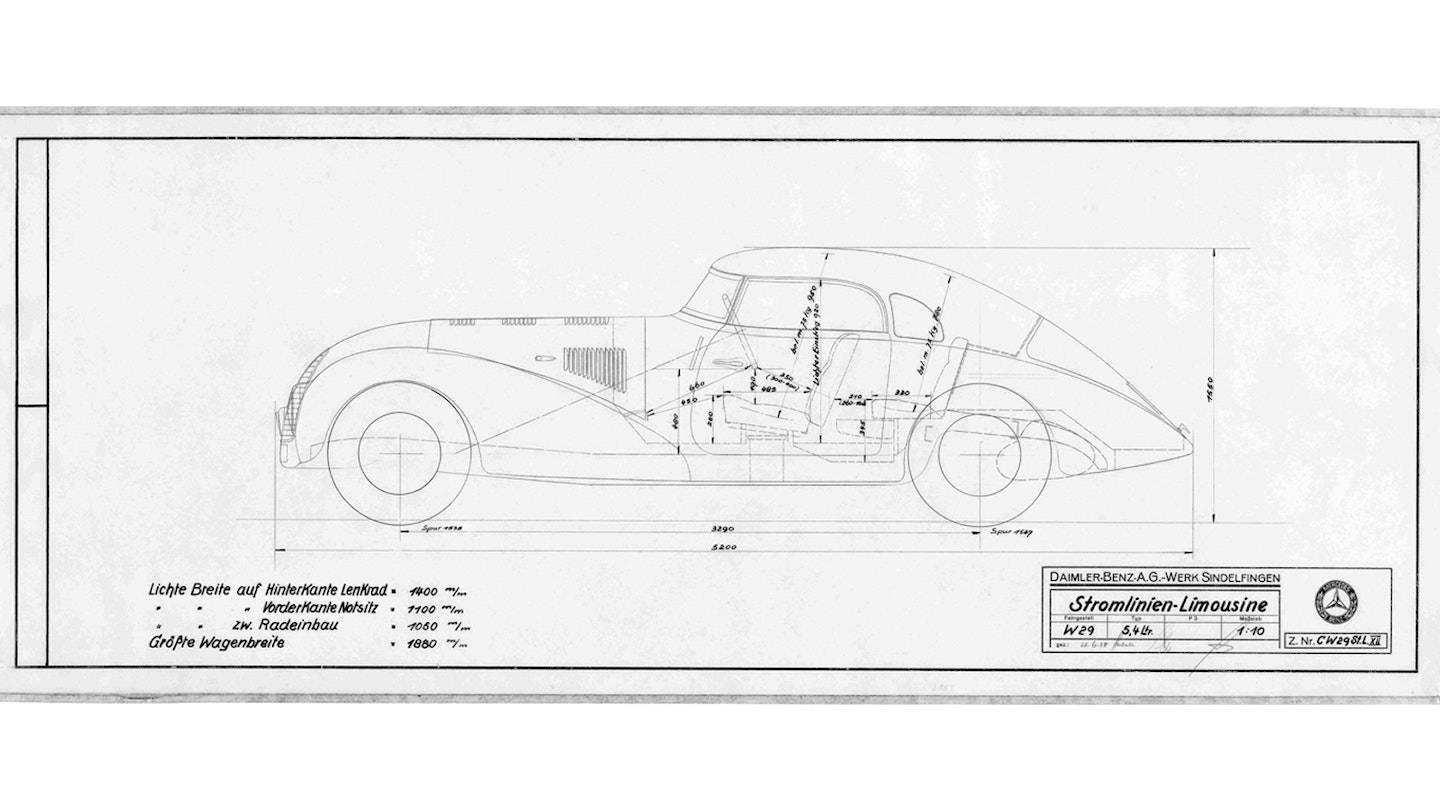

‘The hardest part of recreating the body was using the Linienrisszeichnung – a very complex technical drawing,’ Ralph says. ‘A craftsman of the Thirties would have had no problem reading it, but that knowledge is not very common any more.

‘So we had to translate the language of the Linienrisszeichnung into today’s technical terms. It gives all the necessary details to convert two-dimensional metal sheets into the three-dimensional form. Our experts studied it and converted it into a modern CAD data set to produce the 3D body.’

The team used the data to laser-cut a series of profile templates that could be built into a framework to create a buck over which each panel could be formed.

Typical of the period, the cabin structure is formed by a wooden frame. ‘Our main sources were the drawings. Here the wooden frame was very well-described. We also had some photographs from the rear, where we were able to see the open trunk. But we sometimes had to extrapolate from the existing information. For example, some detail of the design of the lower interior was missing. We used the craft methods of the Thirties to produce the frame. It is made of ash – the classic material for a body frame structure.’

The outer body reconstruction started with an exciting discovery. ‘I found a piece of aluminium screwed under the side of the frame. It looked like the remnants of a body that had been cut off. In the archives one of the references mentioned bodywork in light metal. The piece was 1mm-thick duraluminium, as used on aircraft and some racing cars.’

Another revelation soon followed. ‘In the photographs I’d seen small ribs where the bodywork appeared to tuck under the chassis to form a belly pan, but I couldn’t work out how it was attached. Then, in the workshop one night, I had a beautiful moment – I discovered the fillets for the screws in the frame sides.’

The split windscreen and side screens brought their own challenges. ‘We had to recreate the perfectly bowed shape to follow the natural ideal of an aerodynamic water drop.’ The screens were first made in metal to get the shapes right and ensure they would drop down properly with the winder mechanism, before being translated into glass.

‘We had a very emotional moment when all the parts of the Stromlinienwagen body were laid out as a whole in the workshop – not assembled and without chassis. That was the first time we saw the complete shape of the car, and it stunned us by its design and the sheer size. The second emotional moment involved hard work: eight of us lifted up the body and set it on the chassis – it fitted, with all the mount drillings lining up.’

Engine and interior

‘With a project like this – a mixture of restoration and recreation – you have to take care of all the original parts found. But with the parts that aren’t there, working out what to do based on careful archive study is the only way,’ Ralph says.

For the mechanical parts, replacing missing items was relatively straightforward because the drawings and other references showed that the streamliner was standard 540K beneath all of that swoopy aluminium.

‘We’re lucky to get a lot of these parts from our storage halls, but we also had to search on the free market just like everybody else. For example, the engine is an original 540K unit that we had in our collection.

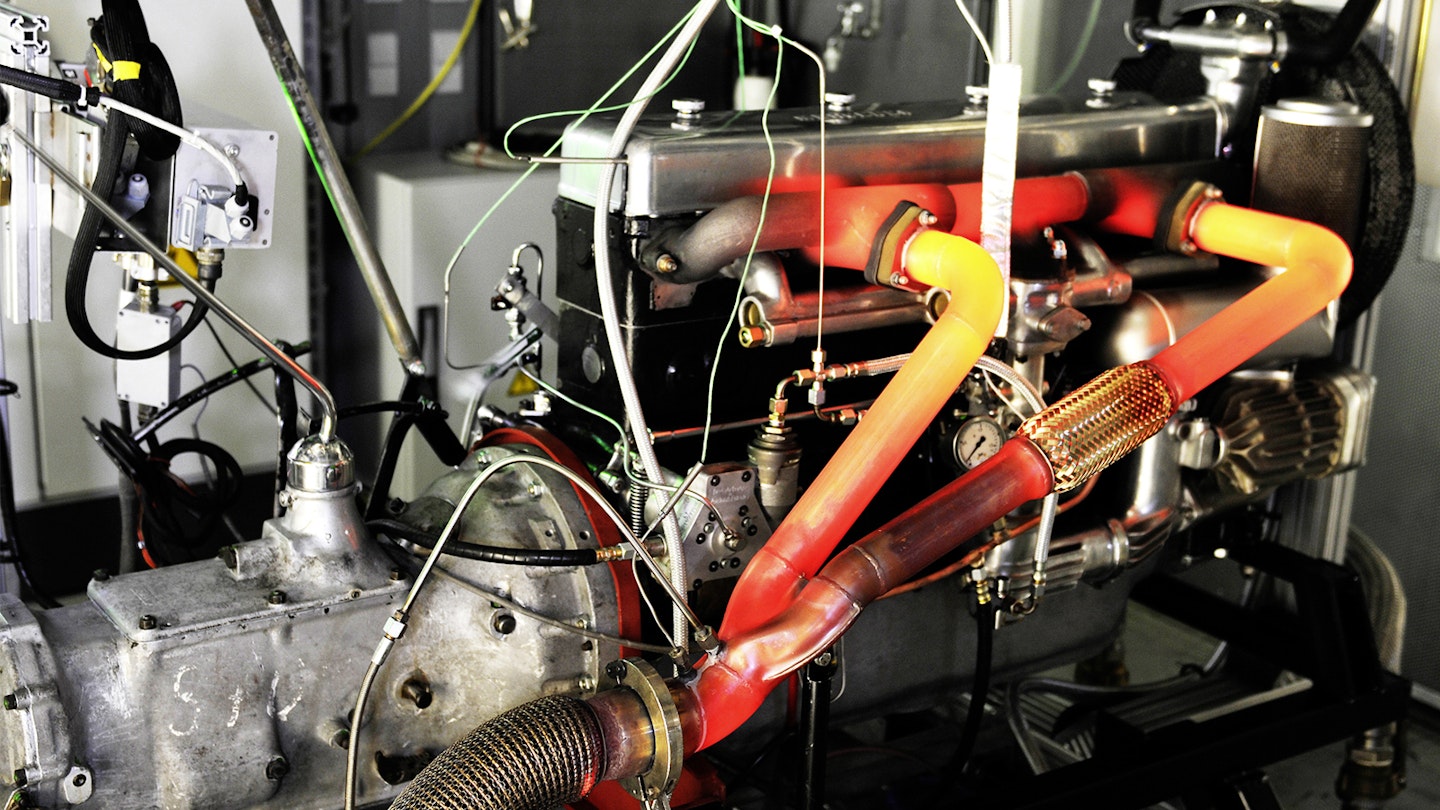

‘To make sure it was exactly right in terms of technical performance and historical accuracy, the engine got a complete overhaul in a our technical service centre. Finally, we tested it on a modern test bench in our plant in Untertürkheim.’

The 5401cc M24 straight-eight is good for 115bhp at 3400rpm, with 180bhp available in shorts bursts with the wailing Roots supercharger engaged.

Recreating the interior was more difficult, calling on a mixture of scrutiny of limited reference material, and knowledge of how similar Mercedes would be finished.

‘We had very few – but good – pictures, which were very useful for the dashboard. We only had pictures from outside the car, but by enlarging the areas around the glass we could make out some details.’ From one angle it appears that the dashboard is curved to follow the shape of that wind-cheating front screen, unlike the flat arrangement of a regular 540K.

Items deeper in the cabin called for a little more extrapolation. ‘Based on other cars of the time, we had to interpretatively add these details, putting our minds back into the time of the original stylists and designers.’ Given the original purpose of this car, it’s a fair assumption that much of the interior would have used familiar parts and materials.

‘We did have the original records of this car, which said the headliner cloth and leather upholstery were grey. We chose the colours to be as exact as possible. Same for the wooden dash – we made it from nutwood, which was available for the 540K in 1938.’

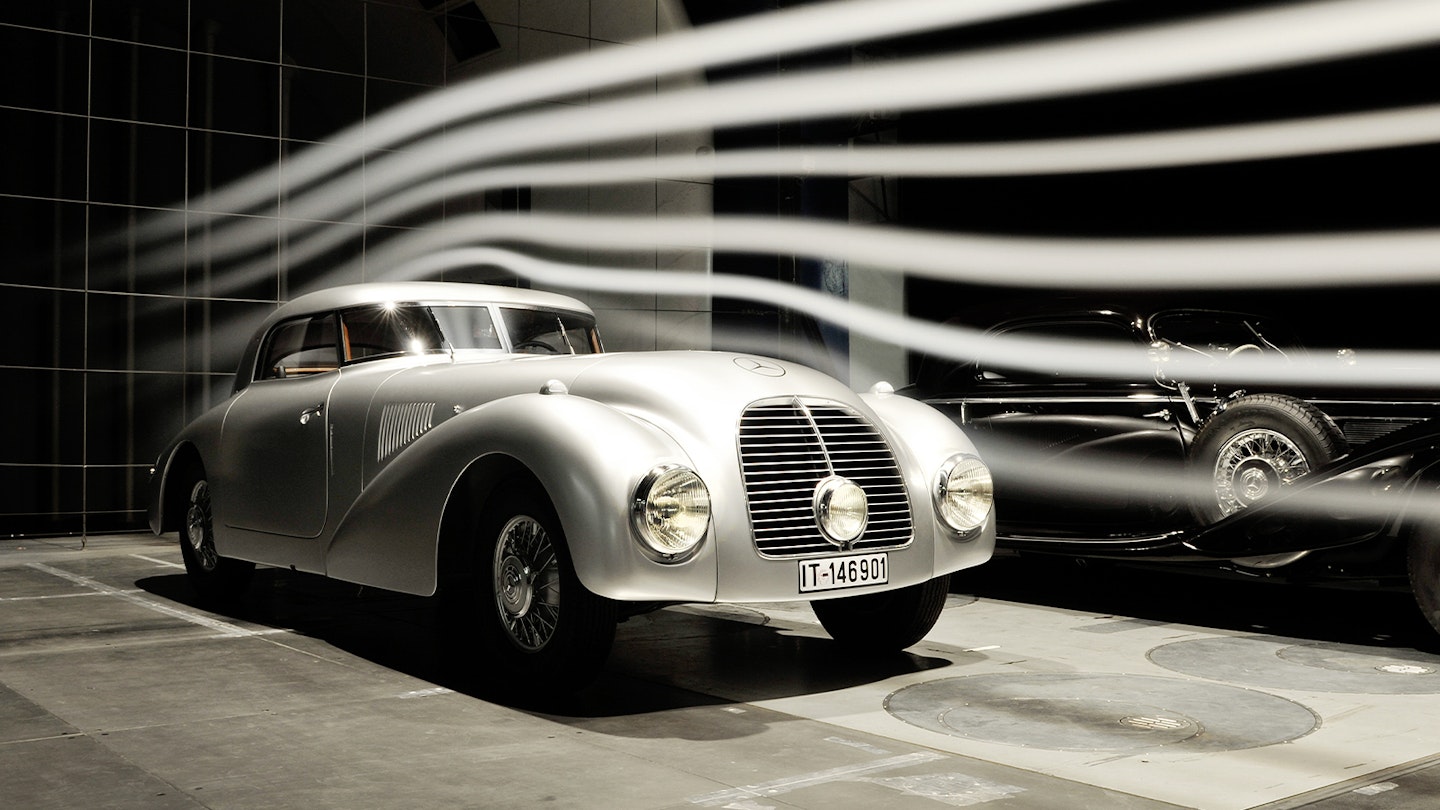

In the wind tunnel

Having restored the Stromlinienwagen the team couldn’t wait to find out how aerodynamic it really was. Martin Konermann (left), whose day job focuses on modern S Class aerodynamic development, did it as an after-hours project. ‘I was very excited because I love the streamlined shapes of the Thirties. We tested it in Mercedes’ full-size wind tunnel in Stuttgart Untertürkheim, the oldest functioning car wind tunnel in Germany. It was a step back in time to see how my former colleagues in the Sindelfingen Sonderwagenbau had realised, in detail, a streamlined aesthetic body on this luxury car and how good the aerodynamic performance really was.’

Martin takes me on a tour of the tunnel, once part of the university. It’s a Göttinger Windkanal closed-tube design built in 1939-43, essentially a four-sided loop with baffles to make the air turn the corners, a vast 5000kW fan, a stator to prevent the flow from spiralling and changes in ducting to channel the air from 80km/h up to 250km/h over the car.

As I nervously step between the vast blades Martin describes his tests, completed just two days previously. ‘The airstream followed the rounded front with the integrated head lights perfectly. There are no bumpers to disturb the flow. The airstream followed the shape of the streamlined front fenders without causing any vortices in the wheelhouses.’

He explains that one of the biggest factors to get right with a design is optimising the flow of cooling air into and out of the engine bay with the flow around the car. ‘Most of the cooling flow left through the louvres in the bonnet without generating much drag. That’s much better than it exiting beneath the car.

‘The greenhouse is boat-tailed well and the smoke tufts followed the body down to the rear numberplate before separating. The wheel houses of the rear wheels caused little wake flow. Today, perhaps, you would add some spats.

‘Apart for some sections of the engine bay and cooling flow outlets the underbody is totally covered by the undertray for undisturbed underbody flow.’

The Stromlinienwagen was tested against a 540 Coupé for reference and Martin was surprised by the results. ‘The regular car gave a Cd of 0.57, and the streamlined car 0.36. That’s amazing for the time – such figures didn’t become normal for passenger cars until the end of the Sixties.’

The need to base the car around a regular 540K, complete with the towering Mercedes radiator hidden behind that slippery nose, meant the streamliner ended up with a large frontal area: 2.489m2. But that still beats the Coupé’s 2.598m2.

I wonder what could be done differently with the benefit of modern aerodynamic thinking.

‘There’s really not much to improve,’ he says.

Behind the wheel

The first time Ralph Hettich drove the 540K it was a white-knuckle ride without any of the bodywork. ‘It was on the Einfahrbahn in Stuttgart-Untertürkheim in March 2014. It was quite a challenge, driving at 130km/h (80mph) without the bodywork while checking that everything was functioning correctly. The next time I drove it it was complete, just before the wind tunnel test. It was like driving back to the future – it’s amazing how far ahead of its time the car was.’