Anthony Smith bought this Dino as boxes of bits, planning to assemble it in a year. Until he discovered how much was missing and wrong

‘It’s Sunday morning, 6.30am, and I get a call from a guy telling me he knows of a stripped Dino 246 GTS. He informs me it is almost complete, ready to assemble, has some new parts and is very expensive. A similar call a few years before had led to the restoration of a 365 GT 2+2. I remembered thinking that I had been mad to take on that project and that I would never do anything like that again. Yet later that day I am in what seems like a small castle, four hours from home, agreeing to buy a stripped and cut-away shell and several crates of spares.’ So began Anthony Smith’s ambitious Dino project, about which he reflects, ‘I was more stupid than brave.

‘The next three weeks were spent sorting out the crates of parts, revealing not only that vital bits were missing, but many that were present would need replacing.’ Reality had hit home, and Anthony doubled his planned timescale for the project to two years. It wasn’t all bad news, though. ‘The wheels had been refurbished, there was £4000 worth of new panels (according to a bill), the bumpers had been rechromed and all suspension parts had been stripped and powder-coated.’ Then again, that list contained some mixed blessings, which we’ll come to later.

Anthony started getting quotes for having the body done. ‘When I heard that Steve at Barkaways had already restored 17 Dinos, I went with them. They picked it up in October 2012, leaving me to get on with chasing down the missing parts. That included importing from Italy a new-old-stock rear window and surround, when it turned out the carefully wrapped one included with the car was Perspex, plus quarter-light windows and frames sourced from Luppi, who made them for Ferrari originally.’ That provoked a revealing entry in the diary Anthony was keeping of the restoration. ‘This month I will definitely have to hide my Visa statement from my loving wife Pat.’

The plan had been to assemble the Dino himself, with the aid of a friend or two. ‘But once I saw what Barkaways had done with the body I realised they had all the expertise that I haven’t, so agreed they would complete the car. The rise in Dino values helped justify the extra expenditure, especially when I realised I wasn’t just putting together a nice driver but was doing a concours build. And that adds £50,000-plus to the bill.’

Body & Chassis

‘Arch repairs had just been spot-welded and riveted on’

‘We’ve done a lot of Dinos and this was probably the worst. Not so much for rot, but because lots of previous work had to be unpicked and redone, and so much of the body was cut away and missing. It was lucky we had other Dinos in the workshop to refer to.’ Steve Williams is Barkaways’ bodywork wizard, with many years spent restoring Ferraris, and Aston Martins before that. ‘These days we’re not just restoring corrosion and old repairs, but improving on Ferrari’s work; it’s what’s expected now from customers.

‘Before starting work we had the shell stripped by a company called Soda Blaster so we knew exactly what we were dealing with. This car’s chassis was pretty good – the side rails had been replaced – but other areas were awful. Wheelarch repairs had just been spot-welded and riveted on. I redid them by butt-welding new sections in place. New door skins had been fitted, but poorly and to rusty frames. I had to unpick them, make up repair sections for the frame, then refit the skins correctly.

‘In the end pretty much all the metal below the swage line was replaced, but that’s quite usual with Dinos. New sills came with the car, but I had to make up new inner and outer rear valances, and the bowl sections of the rear wings behind the wheels. I also had to let in strips of metal where the roof joins the rear wings below the side vents – Dinos often go there.

‘Once complete, the whole body was skimmed with a layer of Plastic Padding Ultima filler then blocked by hand to perfect all the lines and flatness. It’s the only way to deal with 50-year-old panels that often weren’t that straight originally. It also helps us improve the shutlines and swages. Getting all that exactly right is where much of the time goes.

‘Before the paint stage, one of our tech guys did a dry-fit of all the trim – bumpers, badges, lights. Almost every bit had to be altered before being plated as these cars were all hand-built, so nothing fits off the shelf.’

Paintwork

‘Special “day lights” show up any imperfection in the body’

‘The pressure is in the level of quality we set ourselves, and every paint job I strive to make better than the last.

‘We’re under so much scrutiny. It’s not just to please the owner; these cars appear on the world stage.’

Sean Savage has been Barkaways’ paint man for 18 months and was recruited from a specialist high-end sports car coachworks. His challenge was to make the Dino’s paint look better than Ferrari managed to back in the day – a lot better, as that’s the expectation today. Only perfection will do.

‘The secret is in the system, which is followed for pretty much every car I paint. Starting with 120-180-grit paper to refine the shape, I worked down through 240- and 320-grit, alternating between short and long blocks, smoothing it all out. Then I blew over a guide coat and flatted that out with 1000-grit wet and dry to reveal any remaining imperfections in the filler work. Then it was on to the primer stages.

‘Two litres of acid chromate etch primer were followed by seven litres of high-build primer. This was left to settle and let all the solvents out for a month before being block-sanded back with 320-grit to iron all the body out and define the lines.

‘Then I did it all over again, finishing off with a final flat with 1000-grit. It makes our job much harder but is worth it in the final result.

‘For the Rosso Chiaro topcoat I used a solvent-based ICI two-pack – 20 litres of it once mixed, and the same amount again for the lacquer coat.

‘I wanted a lot of material on there as after the paint had been left for a week to settle, I spent two more weeks wet-flatting it with 1200-grit, then 2000-grit and finally 3000-grit, getting rid of the finest imperfections. In all our workshops we use special “day lights” (full-spectrum fluorescent daylight tubes) to show up any imperfection in the body. It’s something that takes us to the next level. And the boss, Ian, is even fussier than our customers. But then it’s his name over the door.

‘My final job was to mask it all up and add all the correct matt black paint around the engine bay, bonnet shuts and sills. That all gets matt lacquer applied over it – it gives the finish they class as original.’

Running gear

‘The engine and box were on the floor with piles of boxes’

Ian Barkaway handled the running gear himself – he’s been rebuilding Ferrari engines since 1986. ‘It was all an unknown quantity – the engine and gearbox was just sat on the floor with piles of boxes. One of those “oh crikey!” moments. All we could do was pull it to bits to see what we had. Luckily there were no horrors; it had obviously been running but had stood for years so needed re-doing.

‘I fitted forged pistons, hardened valve seats for unleaded fuel, and new solid valves in place of the sodium-filled originals – the heads fall off those. I used phosphor-bronze valve guides too: all better-quality stuff than original, right down to the gasket sealants. Then everything was finely balanced – Dinos are notoriously bad on that score.

‘With the V6’s very short stroke and wide pistons it’s critical or the engine won’t last.

‘All the sandcast casings like the cam covers were a bit cheesy – they often are – so we have to dress all the castings to true up their mating surfaces to get a good seal and keep the oil in.

‘The gearbox was similarly good, I just went though it and replaced all the bits that usually wear out: main shaft bearings, synchros etc, but kept the original gear train. For Ferrari Classiche certification you have to keep things like that original. The ZF limited-slip differential was rebuilt, and the diff bearings replaced.

The wheels weren’t great so we sent those off to be refurbished. There are reproduction wheels available, but their features are too sharp-edged and they’re not allowed to use the ‘Dino’ or ‘Cromodora’ logos on those. And again, for Classiche they need to be original, so at £150 a pop for a refurbishment it’s not really worth doing anything else.’

Then there was the wiring. ‘We left the core loom in place and started by removing all the crap we found on it – wires for old stereos, alarms, all the stuff that shouldn’t have been there. Then we ran new wires to all the extremities. One sticky problem was that there was no key for the ignition switch.’

Anthony had searched all the crates of parts. ‘In the end we had to remove the switch and send it to a locksmith. They stripped it out and made new keys to match the tumblers.’

Assembly

‘Don’t buy a car in boxes – get one that’s complete’

‘It’s been challenging; in fact everything with this car has been an uphill struggle. Boxes of stuff arrived, not all of which was to do with a Dino.’ Matt Sheppard (left) has been with Ian at Barkaways since day one, and was in charge of this car’s assembly.

‘Even some of the work that had been done needed re-doing: the heater boxes had been rebuilt, but the matrixes had been put in the wrong way round. And the wishbones had been repaired but they’d been welded in the wrong place, which had twisted them.

‘One big issue was the glassfibre floorpans and bulkheads. These had all been cut up and removed some time in the past to make it easier to do the chassis repairs. This was like getting a jigsaw with no picture on the box, with the added challenge that if the glassfibre floor is not exactly right, the console and handbrake don’t line up properly.

‘The dividing section was missing between the engine bay and boot – we had to make that. It was the same with lots of other small parts that you just can’t go out and buy. We had to make much of the handbrake assembly, pins for the front of the roof, and one of the rear plastic guides for the door window was missing so we machined the other out of nylon. It would have been even more of a nightmare if we hadn’t had another GTS in to refer to. Even then we found some answers by Googling for images. Don’t buy a car in boxes – get one that’s complete. You can’t just take a part from another Dino. They were handbuilt – so even if you do find something, it won’t fit without modification.’

Even parts that were present created work, like the fuel tanks. ‘You can’t buy new tanks and one had rusted badly enough that we had to make a new bottom for it; the other one merely leaked. And the drop windows on these are always a pain; they have weak motors and the channels don’t line up. I spent days lining up the new quarter-light frames with the A-pillars, then more getting the windows to run up and down and shut properly. A lot of it was like that – you are constantly battling design with these cars, so if you can make something function better along the way you do.’

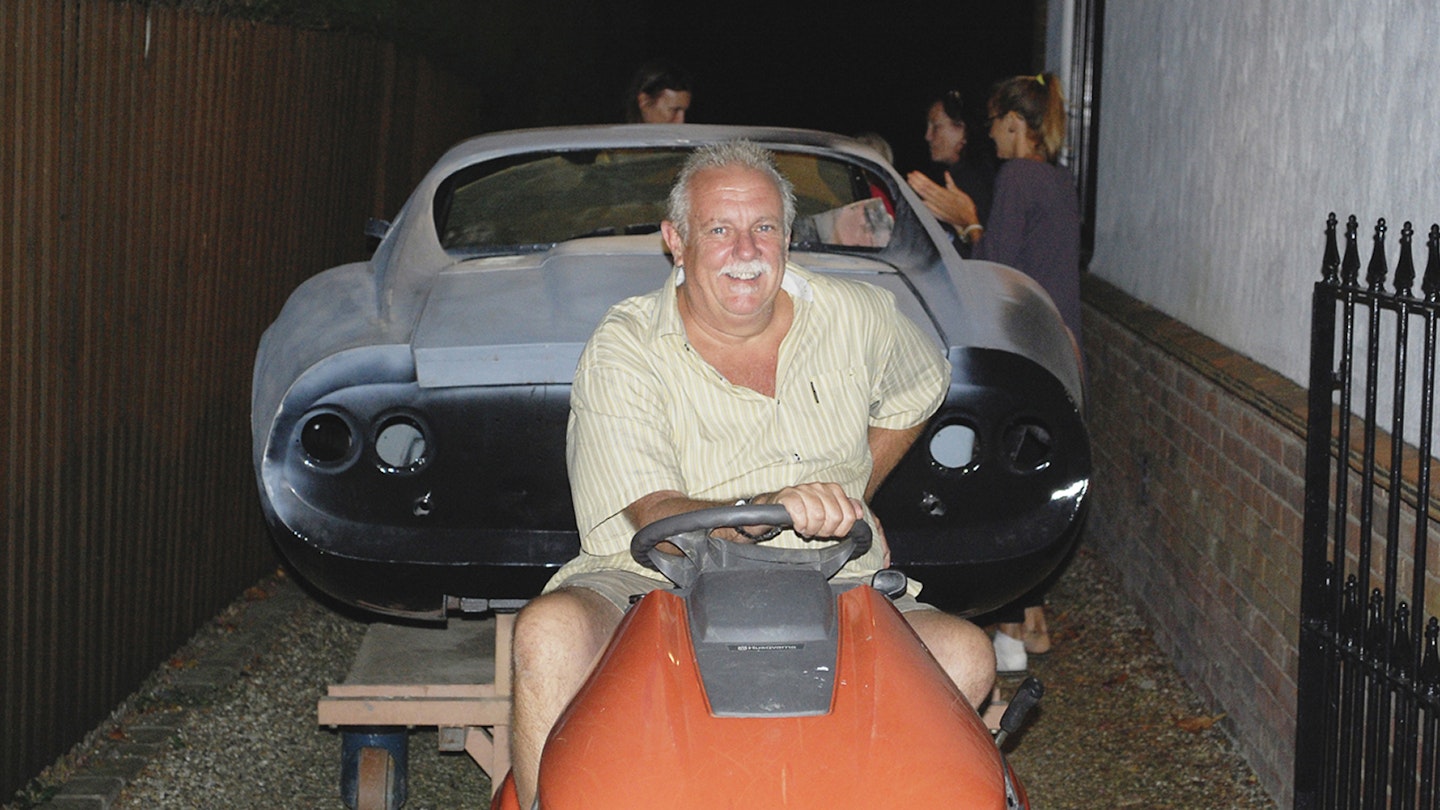

The result

Anthony Smith admits to being speechless with emotion when his Dino was unveiled at Barkaways’ open day. And that from the former boss of Wolfrace Wheels, who has four other Ferraris in his garage and has owned a Dino before. He says, ‘The car looks stunning and my only fear is that it’s maybe too good to use. Does that make any sense? I had said that when it was finished we would drive it to Maranello; now I’m not so sure. I have mixed feelings on this one: my heart says what the hell, it’s only a car and they are there to be driven; but my head says you have a lot of money invested here, be sensible. I hope I can get these thoughts out of my head and just enjoy it.

‘It has been an exciting project, at times quite emotional, and certainly with its fair share of highs and lows. The most difficult part was trying to track down missing parts. Most could be found, some had to be remanufactured. Anything is possible, but unfortunately it all comes at a price. That said, Ian Barkaway has been such a nice guy to work with – he held my hand. Would I do it again? Yes, bring on the next project Ferrari!’