Restoring an Eighties supercar icon is a tough task for anyone. But doing it in the name of Porsche itself – in just six months – complicated everything

‘This all began when one of my neighbours came round for tea,’ said owner David Graves. ‘She knew I was into classic Porsches – I used to work in the sales department of Porsche Centre Leeds from 1997-2005 – and said she knew of an old Porsche stuck in a garage in Ilkley. Its owner had moved to Jersey 15 years earlier and hardly went back to the house.

‘It took me six months of negotiating with the owner before I could even get access to the garage,’ Graves says, ‘and all I knew about the car was that it was red but when I pulled open the garage door and saw the wide bodywork and the boot badge, I nearly wet myself. I was born in 1970 and bought a poster of a red Turbo in 1980, so it’s my dream car.

‘It was looking sorry for itself, but it was all there. When I opened the door there was a mouse sitting on the back seat looking at me, but most of the interior was strangely good for a car that’d been sitting for 15 years. I had a 1969 911T but I couldn’t afford two Porsches so I sold it. The money raised would cover the buying and restoration of the Turbo. I haggled the owner down below £30k, and spent £3k at Strata in Leeds getting it running, but I ended up driving it only as far as the restoration centre. I’d planned to do the restoration myself until I took the wings off and realised how rotten it was, but then Porsche Centre Leeds said it needed a Turbo for Porsche’s annual Restoration Competition, and the team would do it in six months.’

Bodywork and paint

‘We got there in the end with everyone working Saturdays’

‘I didn’t realise how bad the car was until I chemically stripped the paint and beadblasted the body with tiny black plastic balls. It came back looking like a teabag,’ said Andrew Harrison, general manager of the Leeds-based JCT600 Body Clinic. ‘The inner wings, door panels, doors and spring hangers were the worst areas.’

As far as Harrison was concerned, getting the restoration right meant returning the car to its as-new state of 1980. ‘We put it on a body alignment jig to hang all the new panels, but they weren’t as critical of panel gaps in the Eighties. We could’ve done it ten times better but we didn’t want to detract from originality. The panel beaters were under a lot of pressure – it’s frustrating for a professional to have to do what seems like a sub-standard job, but spend time getting it perfectly imperfect too. We got there in the end.

‘A flat finish would be out of character,’ he said. ‘We had to create an orange peel effect on the insides of wings, sill bottoms and so on. We used solid 68-line [levels of paint thickener] Guards Red – normal paint is 23-line. It’s hard to replicate the orange-peel look exactly while protecting the car properly, so we sprayed test panels at different room temperatures until we achieved the right balance.’

Engine and mechanics

‘We wanted to keep the engine looking as original as possible’

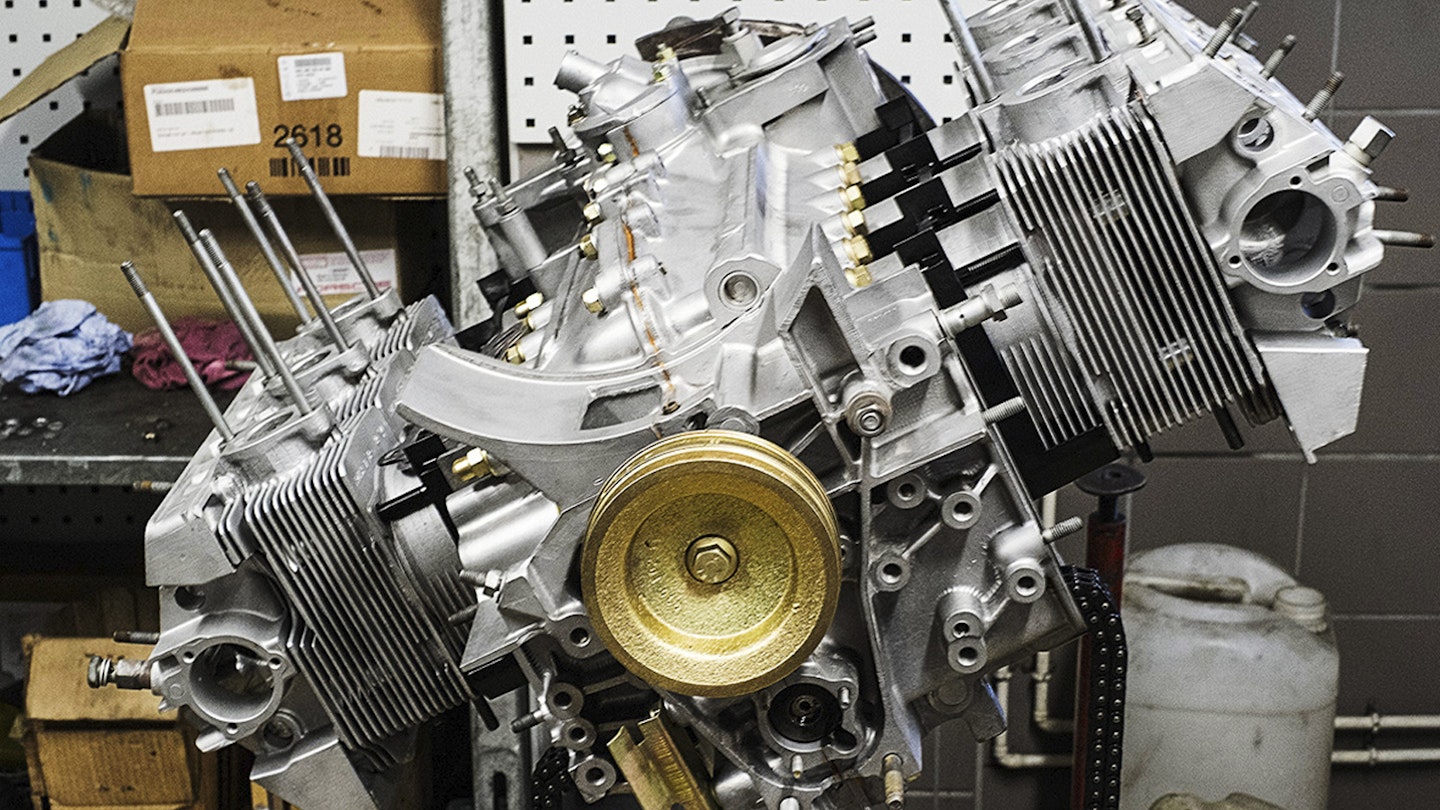

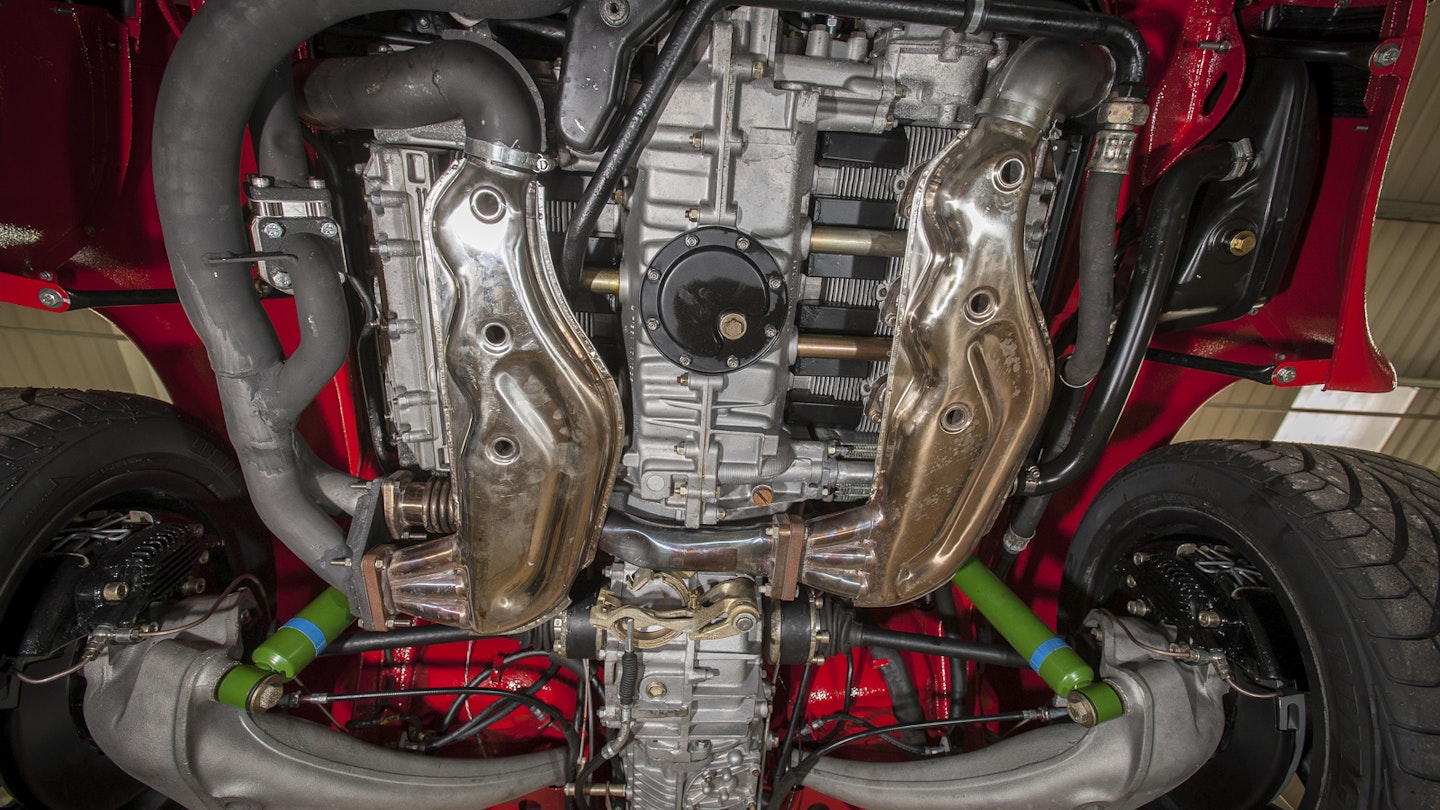

‘When I first saw the engine, all the tinware on it was rusty,’ said Porsche Centre Leeds’ flat-six expert Andrew Wexham. ‘Those fins and baffle plates were all badly affected, which would’ve inhibited cooling and engine efficiency. I don’t know whether the car was driven with the engine in that state before it was stored, but all the aluminium parts, nut fittings and oil pipes were corroded and there was more oil on the outside of the engine than inside. Amazingly, it did start and run when we first got hold of it, but I didn’t want to take it down the road to see how healthy it was in case it made it worse.

‘As with the bodywork, we wanted to keep the engine looking as original as possible. This meant retaining as much as we could, so we shotblasted and powdercoated the oil cooler pipes rather than replacing them. We had to get new internal oil tubes for the engine block, though – they rot anyway, especially at 30-plus years old.

‘Then we set to work on the corroded aluminium crankcasing and rocker covers. Again, we didn’t want

to replace the originals, so we used a technique called vapourblasting – it’s like sandblasting, but it uses a much smaller, almost aerosol-like jet and the finest grain of sand possible. It feels like dust in your hands, but it’s great for blasting intricate surfaces, especially those covered in cooling fins, without risking the pockmarks you get with coarser sand grains.’

The turbocharger complicated matters, though. ‘We had to get a new wastegate. The bolts holding it in place were completely seized, and when we finally managed to loosen them, the entire assembly crumbled apart as it came off. New 930 wastegates are very expensive from Porsche – £1500 for an exchange part – but I found this one via the internet in America for less than £1000. Reconditioning the turbocharger would have been too expensive. It needed new bearings and seals, so we sent it to a specialist who had it sitting on a bench for three months, unsure of how to proceed, which made us anxious because time was running out.

‘Parts availability is a real problem. Porsche is starting to remanufacture parts, but it’s an ongoing process based on feedback from restoration centres like ours making recommendations. But of course some bits, such as the wastegate, are just too expensive to justify remanufacturing. In the end we had to buy a new turbocharger from AET Turbos in Normanton.

‘It needed new rocker cover gaskets too. The originals were split and leaking badly because the rubber had hardened. The gearbox and clutch needed little work. Other than oil leaks through its paper gaskets, rusty through-bolts and surface corrosion on the casing, the ’box was pretty good – it didn’t need new synchromesh rings and we could use the original clutch cable.’

Running gear and brakes

‘I knew I was in for some late nights to get it all done in time’

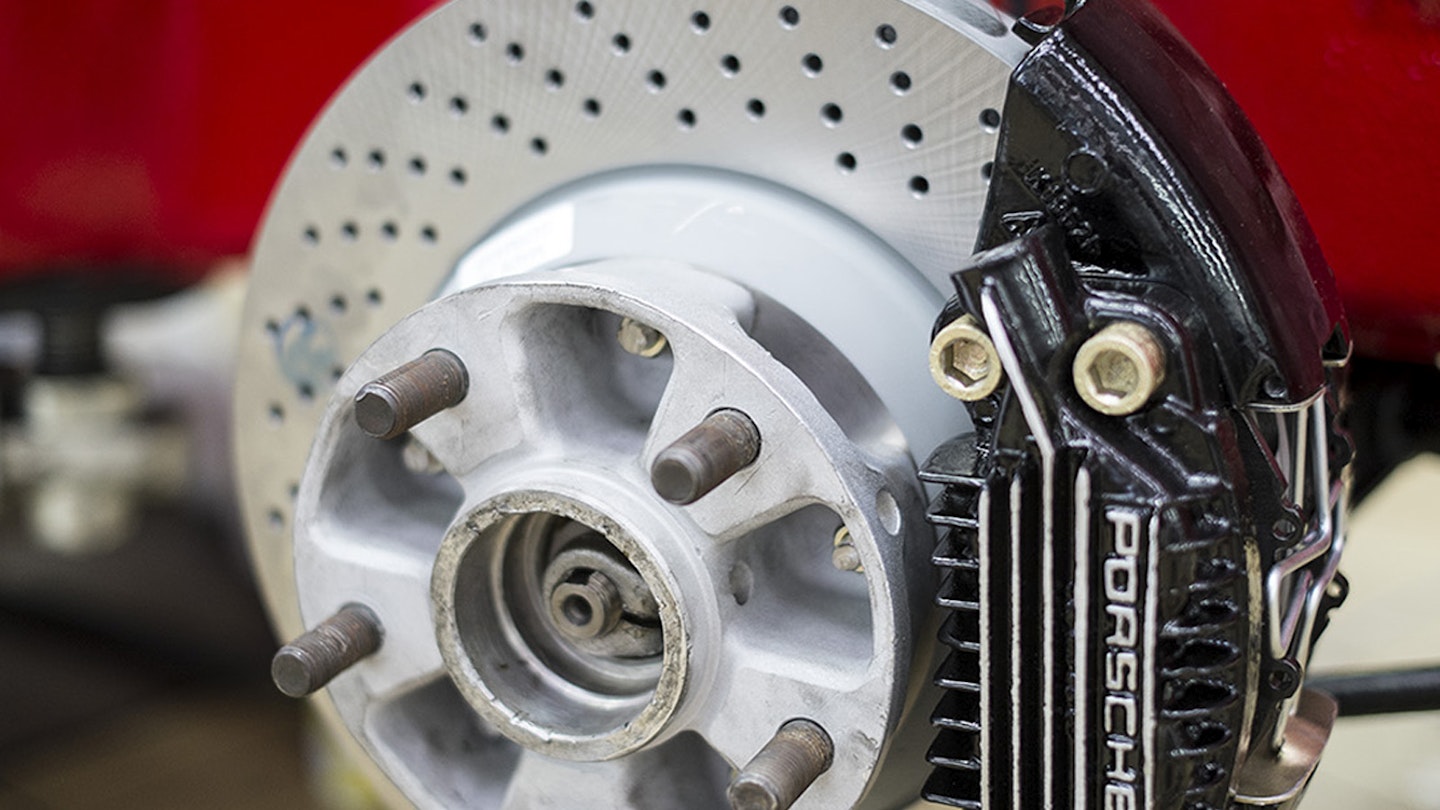

‘The calipers were seized, the pistons jammed, the handbrake cable stuck and the wheels were scraping on the inside of the wheelarches,’ said suspension man Jack Clarke of the mess that confronted him when the car first rolled – with some difficulty – into the workshop. ‘And then came the brief that we had to keep as many original parts as possible – sandblasting and zinc plating, rather than replacement – and have it all finished in a matter of months. I knew I was in for some late nights to get it all done in time.

‘The calipers split into four different sections when they came off – the screws were scrap and needed drilling to extract them. We ended up having to cut the old handbrake cable out – it was seized on, and perished seals had let the brake fluid out and condensation in. In isolation, just removing and stripping the brakes took an entire day.

‘Much of the running gear was corroded, including the driveshafts and steering rack. The shafts were stripped down, shotblasted and zinc-coated, so they shouldn’t rot again, but the steering rack needed replacing, along with the steering arms. The only bits that were worth saving were the rack caps, which we zinc-plated. Surprisingly, the constant velocity joints just needed new rubber boots.

‘We sent the wheels away for refinishing – they had been painted in gloss, but David Graves wanted a matt finish as per the originals.’

‘Obviously it would’ve been dangerous to try and use the old tyres – the tread wasn’t worn through but they’d been sitting so long they’d perished and the sidewalls had split. It was the same story with all the rubber components in this car.’

Interior and electrics

‘New carpets were impossible to find, certainly from Porsche’

‘The leather was in fairly good condition given the circumstances and just needed re-Connollising, but the carpets had been nibbled by rodents and the headlining was awful, full of mildew and rot,’ said interior and electrics guru Andrew Smith.

‘New carpets were impossible to find, certainly from Porsche. In the end we had to get a set made, so we went to Lee Peacock, who doesn’t advertise and runs his business from a farm making trim parts – he just does Porsche carpets. The headlining is very hard to find in this colour – we had to track down new-old-stock items from Lee because they’re no longer available from Porsche, and it was very challenging to fit, especially around the sunroof. The dashboard had to come out too, to get it to fit the A-pillars properly.

‘Sourcing these things was very time-consuming and threatened the deadline date because they’re things you don’t tend to tackle early on in the restoration.

‘Porsche is really going to have to think about remanufacturing some of these parts if it is serious about getting into the restoration business.’

The electrics needed a great deal of work, due to behind-the-scenes damage courtesy of the car’s air-conditioning unit. ‘The fusebox is next to the passenger-side front wing, which had been badly rotted by the aircon pipe because it’s nearly always covered in condensation and had caused some of the worst of the body rust in the wing and adjacent headlamp bowl,’ said Smith. ‘Every wire had to come out before the connections could be shotblasted. The removal is a very involved process because there are no block connectors – not even for the column stalks – just wires and spade connectors, and everything’s separately screwed in.

‘I’d stripped another Eighties 911 wiring loom recently, so I knew how they go together, but everything needed to be meticulously labelled. The washer pump wires had to be replaced because they were badly corroded, but everything else could be saved.’

The results

‘Commitment to originality worked in our favour’

In the finals of the Porsche Centre Restoration Competition, held at Brands Hatch in October 2014, the Turbo won Best Mechanical Restoration. ‘We were only a few points off the overall winner, a 911 3.2 Targa SSE from Porsche Centre Leicester,’ notes Pedley. ‘That car hadn’t been in as bad a state as ours.

‘There were two judges from Porsche and the guest judge, 1970 Le Mans 24 Hours winner Richard Attwood. In his opinion the car was outstanding. It was our commitment to originality that worked in our favour, our decision to recondition rather than replace as much as possible. It may sound minor, but it was things like these airbox clips,’ says Pedley. ‘They’re all original, but they were removed, shotblasted and re-anodised so they look new.’

With the annual competition firmly established and Porsche seeking to push itself as a force in the in-house restoration market, Pedley is keen to see the Leeds centre as a major player. ‘I’m trying to guess the theme for the next restoration competition before it’s announced, so we can prepare ourselves,’ he says.’

Says owner David Graves, ‘It’ll be amazing when I get it on the road. While it was in the workshop I’d forgotten how beautiful it was, then I saw it on the NEC stand and my kids said, “wow, is that our car?!” The Porsche is too nice to take out every day, but it will get used. I can’t wait to take the family out in it.’