Words NIGEL BOOTHMAN Photography RICHARD PARDON

Peeeling off the roundabout, I enter an arrow-straight avenue of trees. I’ve timed it about right – nothing in front as far as a distant vanishing point, nothing behind that might be tempted to chase me. Or try to. The gearing is high so we’ve got quite a bit of second gear to unwind before the up-change, and the car surges forward as the noise builds.

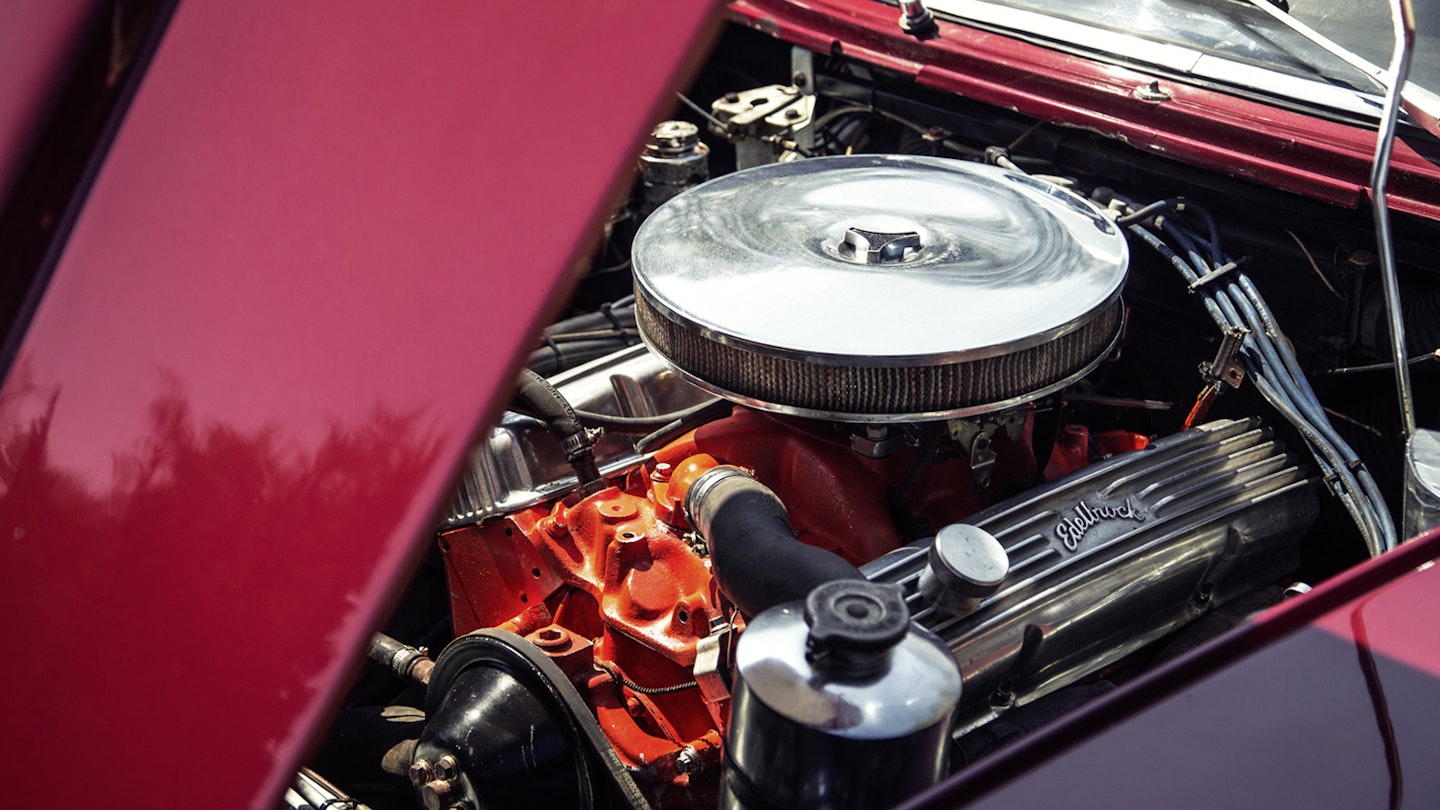

From inside the cabin, it’s a mixture of intake roar, mechanical thrashing and a bass-heavy exhaust growl. Satisfying, but not a colossal hit of adrenaline. From outside, as I’ll discover much later, it’s one of the most intoxicating, thunderous rackets you’ll ever hear from a road car. Grab the next gear at something over 4500rpm – not quite the redline, but then it’s a 50-year-old American pushrod V8, so bending the rev counter’s needle on its end stop isn’t the way to go. The lever is a short aftermarket Hurst shifter; precise but very short in throw, which accentuates the heft of Borg-Warner’s moving parts beneath your left hand. The clutch is a good workout, too.

On it goes. Like all cars with a bellyful of torque, it shoves you forward with a relentless disrespect for mass or wind resistance, at least until you’re well past the speed limit.

Getting to the upper end of third gear is asking for trouble on public roads. Doing the same in top would attract a lengthy ban and probably a shock-horror news report, if the papers got a whiff of it. Classic car nutters in 140mph A-road terror.

Yet this car has actually done that speed along this very road, at least if an oft-repeated tale about the Gordon-Keeble is true. Jim Keeble, the chassis designer and engineering brain behind the marque, is said to have taken every G-K fresh from the factory on a test route through rural Hampshire. He would start at Eastleigh, head up the A3 towards Winchester, drive through the town and then out north-east along the A272, which is where we are now. If it couldn’t pull 140mph along this road or the old Roman stretch of the A30 to Stockbridge, it went back to the factory for improvements.

Sadly, Jim Keeble is no longer around to ask, having passed away in 2003. But his apprentice and great friend Derek Baker (see interview, page 78), believes the story. Keeble was a talented and experienced competition driver, and 140mph in a large, stable car on straight roads wouldn’t have scared him.

The idea of it scares me, though. This is partly due to modern traffic, which is undoubtedly heavier than that of those days in the early Sixties when the cars were being assembled at Eastleigh, now the site of Southampton Airport. Yet even back then, the consequences of a myopic maiden aunt creeping out of a turning in her Ford Pop would have been frightening. At 140mph, Jim Keeble was covering 200 yards every three seconds.

He had at least one factor on his side: the brakes really are tremendous. Even our abbreviated attempt at repeating history has brought up a speed far faster than the horsebox I’ve caught up with, so it’s a pleasant surprise to feel a ton and a half of Gordon-Keeble hauled up so straight and true by its four-wheel disc brakes. The more you drive one, the more you come to expect good manners and sensible behaviour.

A highly-strung exotic this is not – it doesn’t overheat, it starts first time and it never misfires, spits back or otherwise attempts to bite its master.

The theme continues in its layout. There is an abundance of interior space, with legroom, headroom and shoulder room all far in excess of anything enjoyed by E-type owners, or indeed those who bought a contemporary Corvette – the donor of the G-K’s Chevrolet engine. The back seats are narrower than the fronts, thanks to intrusions from the rear wheel wells, but our (admittedly skinny) photographer remarks on their comfort.

There’s no doubt that the Gordon-Keeble is a very well-realised grand tourer. Big boot, lots of light and space in the cabin, a potent engine and relaxed gearing. A decent ride, too. It seems to come from a slightly different place to that of half its rivals; think of an E-type FHC (or later, 2+2), an Aston-Martin DB5, a Maserati Sebring or Mistral, even a Ferrari 330GT, and you have cars with their roots in low-slung sporting machinery – a little suffering is expected and forgiven. Rear seats (if there are any) are for overnight bags, not ferrying friends back from dinner.

The Gordon-Keeble doesn’t offer E-type, Maserati or Ferrari drama on first acquaintance because it feels more like a large saloon than an overgrown sports car. It follows a different objective: civilisation. Think of the V8 Bristols, the Jensen C-V8, the Iso Rivolta. This last comparison is particularly relevant, given the Iso’s tick-list of similarities with the Keeble – Corvette engine, Giugiaro styling, tubular spaceframe chassis, de Dion rear axle, disc brakes.

The Iso’s steel body contributed an extra 150kg of weight over the G-K, leaving it trailing slightly in top speed and acceleration figures. Bit of a shame for Renzo Rivolta, as it was widely believed at the time that he got his engineers to crib the chassis details of the Gordon GT prototype he borrowed in 1960, purportedly with a view to backing the English project. Yet even the obscure Iso Rivolta is probably more widely known than the Gordon-Keeble, at least internationally. That unfamiliarity soon makes itself obvious.

As I wind down from cross-country cruising altitude, I join the clog of traffic into Stockbridge. The pavements are packed with day trippers and shoppers, among them clearly a few car lovers. They’re the ones whose heads turn when the Keeble rumbles past. They don’t smile, point or wave…they frown. It’s not the resentful look an eco-warrior might give to a giant 4x4, it’s a look of intrigued bafflement. It says, ‘Wow, that’s nice. What the hell is it? Did I once see one in a magazine?’

After I’ve been driving the car for an hour or two, I’ve seen this expression so often I feel it needs a name: the Gordon-Keeble Stare of Puzzled Approval. How did a car with so much going for it wind up receiving the GKSPA? Look at what the Gordon-Keeble offered and you feel it could hardly have failed.

Its Italian styling was universally praised and still looks good today, especially when compared to the somewhat challenging Jensen C-V8 and the more upright, restrained-looking Bristols. It wasn’t expensive either: at £2798 in 1964 it cost a lot less than the Jensen (£3861) the Iso Rivolta (£3999) the Aston Martin DB5 (£4249) and the Bristol 408 (£4459).

It was undercut only by the E-type at around £2050, but then E-types were always extraordinarily low-priced for what they offered and it seems somewhat doubtful that Jaguar made any money on them at all.

So what went wrong with Gordon-Keeble? We’re able to hear the full story of Gordon-Keeble’s creation, production and premature demise from an eyewitness on the following pages, but the short answer is that the company suffered a combination that did for several other sporting marques in the Sixties and Seventies: small size and bad luck.

Gordon-Keeble didn’t have much in the bank by February 1965. Sales had been respectable but they were employing just more than 100 people and the cars were not quick or cheap to build. However, the signs were that the marque was sustainable – it had delivered around 80 cars and had a decent order book for something approaching 50 more. Could it outgrow the nervous early stages?

Just at the wrong moment, industrial relations at a component supplier, Adwest, went sour and the company could no longer supply Gordon-Keeble with steering boxes. Suddenly there were 16 cars awaiting delivery – and final payment – but undriveable. Cash flow dried up, half the workforce was laid off and only two months later the receivers were called in. Production restarted after a rescue package got the firm going again in another factory, but only seven cars were built before it folded for good in the summer of 1966.

Those first Gordon-Keebles emerged from production half a century ago, and to celebrate this 50th birthday the Gordon-Keeble Owners’ Club is attempting to get 50 examples together for a series of events over the last weekend in June.

Almost all of the 99 survive, plus one completed later from leftover parts, but not all are on the road or indeed in this country. To assemble exactly half the marque’s production in one place will be a memorable achievement.

Back in the present, we’ve escaped Stockbridge to head back towards Winchester along the B3049. It’s a twistier road than the high-speed sections of the route and gives us a chance to see how the Keeble corners. Before I pitch it into the first right-hander I find myself wishing the steering wheel were closer – there’s some adjustment thanks to a collar behind the wheel, but all it does is move the wheel from hard up against the dash to a couple of inches away from it. Fine for long, lazy cruises, but if you’re heaving a heavy automobile left and right with straight arms, the turning force has to come from moving your shoulders up and down, and stiff trapezoid muscles are guaranteed.

At least you get a nice view of the dash by sitting this far back. It’s easy to imagine a deliberately aeronautical intent in its design, what with production at Southampton Airport, but it seems the ordered rows of dials and switches with that massive, dominant centre console simply look the way they do because of the tubular structure underneath. Jim Keeble was keen on mounting the heavy V8 a long way back for optimum weight distribution and this meant some inevitable intrusion of the bellhousing into the cabin. But thanks to Bertone’s tasteful wrapping of Keeble’s superstructure, it’s very well disguised.

This car has its original steering box – many have been converted to rack and pinion – and it does wriggle a bit over poor surfaces, but it’s by no means vague or sloppy. Allied with an extremely planted rear end you can throw the Keeble round tight-ish bends with no worries about either the front or rear trying to exit the corner before it’s over. You just have to put up with some body roll, keep the power down, and howl through to the next straight.

The factories at Eastleigh and Sholing are long gone, buried under new development, and the rest of the test loop from Winchester back to the edge of Southampton is now the M3, with a bit of tedious urban sprawl to endure near the airport.

There is one unexpected moment of delight still to come, though. When the car’s owner, Michael Culhane, takes the wheel for a cross-country charge back to his house on the edge of Winchester

I get into a modern car to follow.

With the windows down – it’s still a beautiful day – I’m only a few feet behind Culhane when he buries the throttle and the big coupé charges off like an angry bull. The explosion of sound is incredible; from directly behind, all the muffled thrashing from the engine bay is obliterated by a deep-chested exhaust bellow that spits and crackles as the revs rise, turning into something you’d expect to hear departing from Maison Blanche at this year’s Le Mans Classic. Yes, it’s only a Chevy small-block, but some happy combination of exhaust and engine tune combine to create one of the greatest sounds I’ve ever heard a car make.

It’s done something else, too. There’s a man walking his dog along the pavement as Culhane tears off into the distance, and he’s staring at the Keeble. But he’s not wearing the GKSPA. He’s got a totally different look on his face: the biggest, most incredulous, open-mouthed grin you can imagine.

The Gordon-Keeble story may be one of bad luck and a near miss at greatness; but 50 years since the cars entered production, the thrill they can offer is utterly undiminished.

1964 Gordon-Keeble GK1

Engine 5354cc V8, OHV, one four-barrel Carter downdraught carburettor Power and torque 300bhp @ 5100rpm, torque 360lb ft @ 3000rpm Transmission Four-speed manual, rear-wheel drive Suspension Front: independent by double wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers. Rear: independent by de Dion rear axle, Watts linkage, coil springs, telescopic dampers. Brakes Discs front and rear, hydraulic, servo-assisted Weight 1436kg (3160lb) Performance Top speed: 140mph; 0-60mph: 7.5sec Fuel consumption 16mpg Cost new £2798 Value now £32,500-£60,000 Length 4813mm Width 1900mm (est)