This Citroën DS took a return trip to Poland in the course of its extensive restoration – and tested owner John Collenette’s passion for the model to the limit

‘I’ve had a long-term love affair with these cars,’ reflects John Collenette – and there’s no doubt that comes straight from the heart. Look at the photograph above of JPP 171K sitting forlornly on a trailer in its as-discovered state, then flip forward a few pages to see it in its full post-restoration glory – that kind of transformation can only be driven by passion.

Having bought his first DS from a baker near Paris in 1982 John bought another about 10 years ago, after a long-term hiatus from the model. That second DS, a left-hand-drive DS21, is currently being restored; his third, latterly acquired, is an early frogeye ID19 that he currently uses as daily transport. The DS you see here is his fourth. It’s plainly more than just an infatuation.

Most cars in this state would have been scrapped. There’s something about the DS that means people can’t bring themselves to do it

But why restore a car that even Paul Harris and Rad Wojcik at DS specialists Pallas Auto describe as ‘almost beyond saving’? The answer lies in John’s desire to, as he puts it, ‘bring something back to life – like having a new car with exactly what I want on it. I know them Paul and Rad well, and I know they wanted to do something like this. I was more than willing to allow them to demonstrate what they could do.’

Paul takes up the story. ‘The car was found by a friend of ours – it had been in a garage in Sussex for 27 years. Most cars in this state would just have been scrapped, but there’s something about the DS that means people can’t bring themselves to do it.’

With the DS extricated from its long slumber, it was trailered back to Pallas Auto and discussions took place with John. The car is a 1970-build DS21 EFi semi-automatic in Confort specification, but for some reason it hadn’t been registered until 1972. It was also unusual in combining a high mechanical specification with a relatively ordinary level of interior appointment. Little is known about the life it led before being laid up, although the reason for its hibernation would soon become horribly clear once the project started...

Getting it going

We look for a precision in the way the car responds

Pallas Auto starts every major restoration by getting the subject car running again, however rotten or dishevelled it may be on arrival. Rad cajoles them all into a drive around the yard, to see if they have the requisite ‘DS-ness’. ‘We aren’t exactly sure what gives a DS this feeling,’ he explains. ‘But you can find it even in cars that need a lot of restoration, whereas other cars that have perhaps been poorly maintained over the years, or restored by people who don’t really understand the cars, don’t have this feeling. It’s a precision, a lightness of touch in the way the car responds; once we know we’ve got that feeling in a car, we know it’s worth proceeding with the project.’

There was no way JPP was going to turn a wheel with the original engine in situ, though. The water pump had been removed and left off the car, and in the intervening years the engine had seized solid.

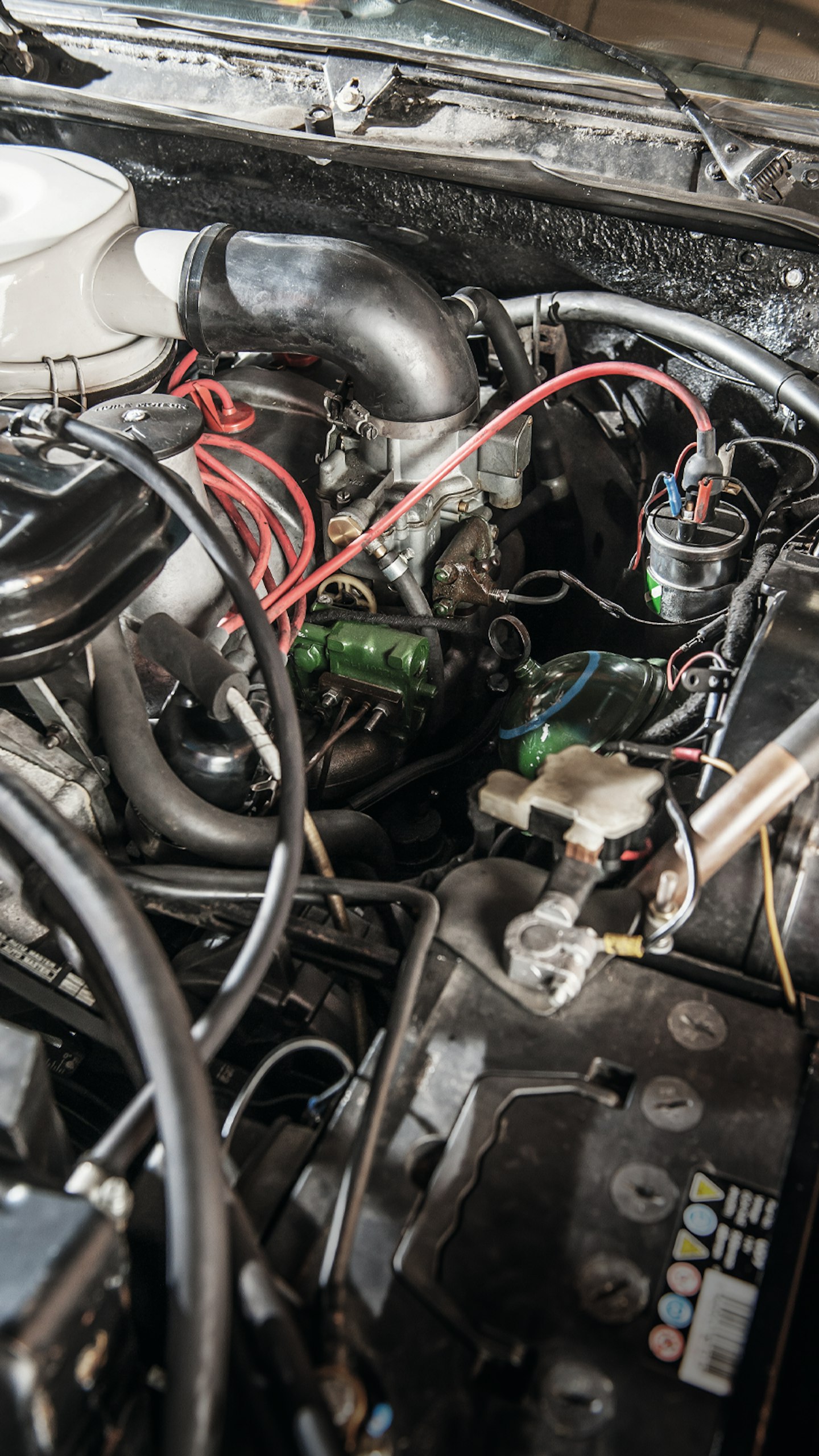

So Rad took another DS21 engine from Pallas Auto’s stock of exchange units and set to work installing it. Many of the rare and expensive fuel injection components were broken or required serious attention, so it was decided to opt for carburettor fuelling. As Paul says, ‘The block and cylinder head have variations, so we used a carburettor block and head from our stock.’

Rad rebuilds the engines for stock during quieter moments, so they’re ready to go when a project arises. ‘Most engines we find are high mileage and in a bad state,’ he notes. ‘The main wear starts from the top: we check the condition of the rockers, cam followers and camshafts, then work down. We then regrind the crank and build the engine up with all new gaskets, seals and ancillaries such as oil and water pumps.’

The same approach is adopted with gearboxes; Paul and Rad prefer to use one from their stock rather than get a particular unit rebuilt. ‘We take a calculated risk with a box we have and put it in the car to try it out,’ says Paul. ‘You can send them away to be worked on, but you’ll often spend a good deal of money and still get it back with a problem. We cleaned and serviced this box, then put it in the car and got lucky with it.’

Finally, there’s the DS’s innovative suspension system. Powered off the engine, it has to be treated in the same way as the rest of the mechanical package. ‘The only real way to test it is to drive the car,’ says Rad. ‘The rear cylinders were replaced, and all lines and hydraulic components were renewed – including the pipes that run in the sills, front to rear. You usually get a few leaks afterwards, but they can be sorted out later on.’

Now JPP was ready to emerge into the daylight to be driven again under its own power. There were clearly adjustments to be made, but the car ran – and, crucially, the DS-ness was definitely there. The car that should have been scrapped was up and running once more.

The next step? Pull it all to pieces again...

Beautifying the body

Do the panels look usable? In this case, no, definitely not!

This restoration is truly a pan-European project. Rad is the principal mechanical brains behind Pallas Auto, and hails originally from Poland. He emigrated to the UK, while brothers Przem and Rys remain in Poland running the family garage.

The metal and paintwork were sub-contracted back to Poland for two reasons – Rad was confident in the standard of his brothers’ work and lower labour costs would make a full restoration more financially viable.

‘The car was sent to Poland on a trailer,’ says Rad, ‘with the mechanical components and interior removed from the car, but the glass left in. This way we use the space inside like a van to transport other components required in Poland for a car that’s already being worked on out there. It works as a kind of conveyer belt.’

Przem takes up the Polish side of the story. ‘Do the panels look usable, we asked ourselves. In this case, no, they definitely weren’t! It was obvious we would need new ones – they were corroded and badly misshapen. The aluminium bonnet was corroded and the glassfibre roof had been damaged. It was in a very bad state.’

With the panels removed, it was obvious that JPP had serious rot in the sills and in the complex rear floor area. The vertical box sections in the latter are hidden from view by a flat panel, which the unscrupulous can replace while leaving the corroded sections behind. JPP was literally falling apart in this area. ‘We cut out the rot in the box sections, just as we did wherever else rust had got at the car,’ says Przem. ‘It needed a new boot floor as well, and attention to the bulkhead at the back of the boot area. This part of the project is pure labour, basically – it just comes down to putting in the hours.’

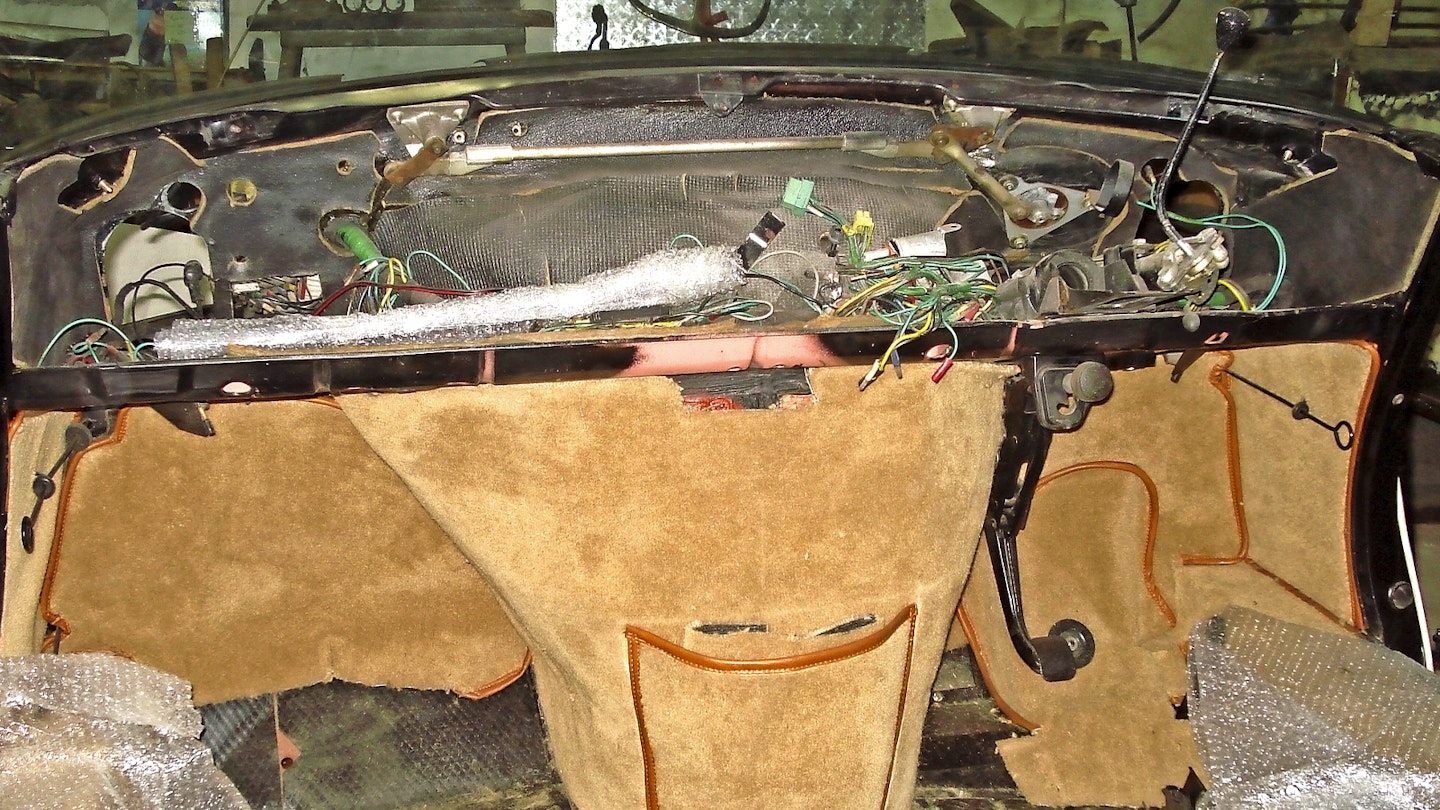

The team decided to use secondhand panels. Even though new ones are now available, Paul and Rad prefer to work with what best fits the car, as well as what’s the most economical option. ‘All the panels were stripped back into their individual inner and outer sections, sandblasted and then repaired where necessary – everything below the swage line in this case,’ says Rys. JPP needed metal repairs to the channels that hold the seals, the cant rail and even the dashboard – it was heavily corroded and had to be stripped right back.

The next step was to roll the DS into the paintshop next door to the brothers’ workshop, where the painter was left to the laborious task of priming, sanding and slowly building a surface suitable for the colour coats. ‘We never hurry the painter,’ adds Przem with a mixture of exasperation and good humour. ‘A lot of DSs have been painted many times, you know... it’s something that just takes time to get right.’

JPP was originally Bordeaux, but John and Paul finally agreed to go for Bleu Platine, which is a correct colour for the year. ‘There was a lot of debate over the colour,’ says John. ‘I wanted a striking colour but not in a gaudy way; it needed to have some subtlety.’

Coming back together

It’s the fun part. Everything is clean and easy to work on

Once finished, JPP’s freshly painted body was transported back to England, where the process of reassembly could get under way in earnest. ‘This is the fun part,’ says Rad. ‘Everything is clean and easy to work on.’ The stainless steel brightwork was refitted, having been restored in Kent, although the Pallas wheels had already been renovated in Poland and a new tinted windscreen put in place.

With the decision to upgrade JPP from Confort to Pallas specification, and with John unconcerned about preserving absolute originality, Paul had a free hand to specify a new luxury interior.

The resultant tobacco brown leather combined with the lighter tan carpets provides a fine complement to the exterior – but it’s crucial that the seats feel right when compressed by your posterior. Continuing the continental nature of this restoration, the seats – which were virtually destroyed during the car’s previous life – were sent to a fellow Citroën restorer in Hungary. ‘We send them there because our contact can restore them with just the right “give” in the cushion and the correct stitching in the leather,’ says Rad. It’s important when you sit in a DS that you are embraced by the seat; some people restore these cars and refurbish the seats so that the filling is much too firm, rather like a German car.’ Rad is absolutely right – you sink into these seats, not perch on top of them.

Having sandblasted the corrosion off the dashboard, replicating the factory metal crackle finish was achieved only by experimentation with differing paints and techniques. Having satisfied themselves the look and feel was right, Paul and Rad then fitted out the rest of the dashboard, replaced the steering wheel with a good, cleaned item from their stock (although they’ve developed ways of rescuing originals too) and then turned their attention to the in-car entertainment.

They opted for a modern system with a retro-look front panel to maintain the period feel, the advantages being not only greatly improved sound quality, but USB and AUX connectivity, along with charging for smartphones and music devices.

From this point it was a matter of working on the details, including the upgrade of exterior trim parts to Pallas spec – although without the rear lamp surrounds that Paul considers too flash – then refitting the tested mechanical parts, with every underbonnet item either repainted or replated, right down to individual bolts.

The result

Projects are harder than building the car originally

‘I’m absolutely delighted with the result,’ says John. ‘I have to say, it does give me a cheap thrill when people notice the car; I’ve lost count of the number of times people have come up to regale me with a story about a DS. A smile comes across people’s faces when they see it, then they do the gesture of the suspension rising up. Even if I’m just going to Tesco, I hop in and the world feels a better place.

‘What have I learned? That these projects are more complicated than you think – they’re harder than building it originally! But there are adventures to be had along the way. Also, it’s better to do it slowly and well – don’t embark on something like this unless you’ve got the patience.’ That approach extends to money, presumably; John puts the bill at approximately £30,000 from start to finish, with at least 50 per cent of that being spent on body renovation. ‘I didn’t do this as a way of getting a great car cheaply,’ he says.

In the year since the restoration was completed, the car has led a busy life. John uses it as often as possible for all sorts of journeys on a daily basis, and has an eye on the future. ‘I’m trying to persuade at least one of my kids that they want one of these to drive around in, and they are coming around to my way of thinking. My daughter’s friends actually think the car is cool...’