Karl Marx wouldn’t have liked this group test. ‘To each according to his need’ doesn’t seem to allow for a clutch of glamorous coupés created for the express purpose of making their owners look and feel good. They’re frivolous and indulgent, of course, but there’s nothing wrong with dreams made real in the metal.

There have been plenty of buyers over the years who are willing to buy that dream. Even in austerity-hit Europe the world of ‘luxury brands’ is never far away from the glossy magazines. But what is especially good for us in the classic car orbit is that luxury items that have fallen out of today’s fashion trend aren’t so expensive any more.

Here are eight covetable coupés that show how. The oldest was made in 1967, the newest in 1982. We have engines with four, six, eight or 12 cylinders, arranged in line, as a vee or flat on their sides. It would be disingenuous to claim we planned it this way, but we have two cars each from Britain, France, Germany and Italy: four of Latin influence, therefore, and four of northern-European background.

The grandaddy here is the car with the biggest engine, the Jensen Interceptor with its 6.3-litre, 325bhp Chrysler V8. Next up, a larger-than-life car whose almost naïvely simple styling makes it look like something smaller that’s been processed in the supersizer. Fiat’s 130 Coupé is a mainstream car firm’s bid for a place at the top-car table in an age before the world became obsessed by the so-called premium brands. There’s a tuneful Italian V6 under that bonnet, just as there is in the next car down the age table, the Citroën SM, which also existed to prove that Citroën can do exotic.

Our BMW 3.0 CSi, surprisingly, is nowadays rarer than the lighter, more fragile but more glamorous CSL version that everyone thinks they want. The CSi has a slightly different appeal, as we shall see. It is often overlooked, and shouldn’t be.

The Jaguar XJ12C you see here is a bit special, being the last one to be made and the proudly owned property of the Jaguar Daimler Heritage Trust. With minimal miles under its wheels, it’s a great opportunity to discover something of what it was like when new. Then, plummeting from 12 cylinders to four, we have a Peugeot 504 Coupé, built and styled by Pininfarina.

Finally we move into the Eighties, beginning with the 450 SLC, with a fixed roof and the rear seats made possible by a longer wheelbase. We finish with the last all-Lancia Lancia, the Gamma Coupé with its concept-car looks and that hefty flat-four engine of possibly undeserved notoriety.

A fashion shoot for cars. A day of sybaritism and sensuality. The catwalk of the Sussex Downs beckons. And the winner may surprise you.

Jensen Interceptor

So far, we’ve hinted that the Interceptor is Anglo-American with its Chrysler engine, but there’s an Italian dimension here too. The preceding 541 and C-V8 models had glassfibre bodies but this Interceptor, launched in 1966 but reprising the name of a pre-541 Jensen, clothed the C-V8-like chassis with a steel body designed by Carrozzeria Touring in Milan. The very first cars also had bodies built in Italy, by Vignale, but thereafter Touring’s design was reproduced by Jensen itself.

And what a great design it is. Its clean, modern crispness is why even the Eighties resurrection of the Interceptor managed not to look dated. That vast, vast rear window is the biggest visual onslaught, framed in stainless steel and acting as a giant tailgate: it’s a true hatchback, the glass held open on hefty spring-loaded supports.

Then there’s the way the Interceptor sits so low, so heavily on those five-spoke Rostyle steel wheels, all power and poise with the short front overhang, the long bonnet and all that tail-glass aft of the rear axle line. You just know this is a mighty, muscular machine. And back in the Sixties, carmakers weren’t constantly looking over their shoulders for retro-tinged comfort. They looked only to the future, which is why the Jensen’s wide, low front grille flanked by quad headlights bore no resemblance to the face of any Jensen past.

Taken in isolation, this could be any then-new Italian or British grand tourer. But such was its impact on the automotive world that its identity as a Jensen was understood instantly. It helped that the Interceptor had an even more glamorous and exotic sibling, the FF, with a yet-longer bonnet and paired grilles aft of the front wheels. It had four-wheel drive and anti-lock brakes; futurism indeed.

There was also, later, the Jensen SP whose triple-carb, 7.0-litre engine had the habit of sometimes continuing to accelerate even when the accelerator was held steady, due to the engine load contriving to trigger, unbidden, the four secondary, vacuum-controlled carburettor band if a motorway cruise met a slight uphill gradient. Drivers could accelerate from 110mph to 130mph without a twitch from their foot, according to the road-test in Motor magazine.

Our Interceptor here doesn’t do that, fortunately. Even better is that, being a Series One, it has the best sort of Interceptor dashboard, with a pair of cowled dials ahead of a large, wood-rim steering wheel and a centre console well stacked with Lucas toggle switches. It’s a catalogue of proprietary parts, but all the more Sixties-British-specialist for that. I’ve not driven an original Interceptor before today, only one of the remakes fitted with a Corvette engine and Jaguar rear suspension, yet the interior feels reassuringly familiar to this British boy.

To my left is the selector for the three-speed Chrysler Torqueflite automatic transmission; I hope the torque doesn’t fly away before it gets to the rear wheels, or gets too dissipated in the slushy slippage of an old-school torque converter.

Sophisticated surge

Time to find out. This Interceptor has gained power steering (a period hydraulic type), and with it the ability to be parked without tearing its driver’s shoulder muscles. The steering is finger-light, contrasting with the weight and meat I can sense through the other controls and from the way the 1676kg Jensen moves on its suspension. Also, for all the engine’s 325bhp it doesn’t feel especially keen; it’s the feared slushbox effect, slipping the torque converter to help bridge the chasms between the ratios that the engine’s torque alone can’t quite span.

The solution is to press the accelerator very hard and trigger the kickdown switch, upon which the engine can break free and deliver the expected surge of thrust to the expected sputtery V8 throb. Driven thus, the Interceptor would live up to its name were there something to intercept, with vivid acceleration measured at the time at 8.3 seconds to 60mph. Alternatively, drivers can hold it in the lower gears manually, but that seems to miss the point.

This is not a car for hustling along a twisty road. I’m very aware of the live-axled rear suspension allowing the body a lateral wriggle and heave over undulations, despite a Panhard rod intended to stop exactly that. Better, then, to cruise in a flowing, decorous fashion, devouring counties and continents, on a grand tour in this grand tourer. Try not to think about the fuel thirst.

Jaguar XJ12C

It’s blue. Very blue. Squadron Blue on the outside, cosseting blue velour – not leather – on the inside. Driving an old Jaguar without cowhide beneath my trousers is an unusual experience, as unusual as seeing just more than 9000 miles on the odometer.

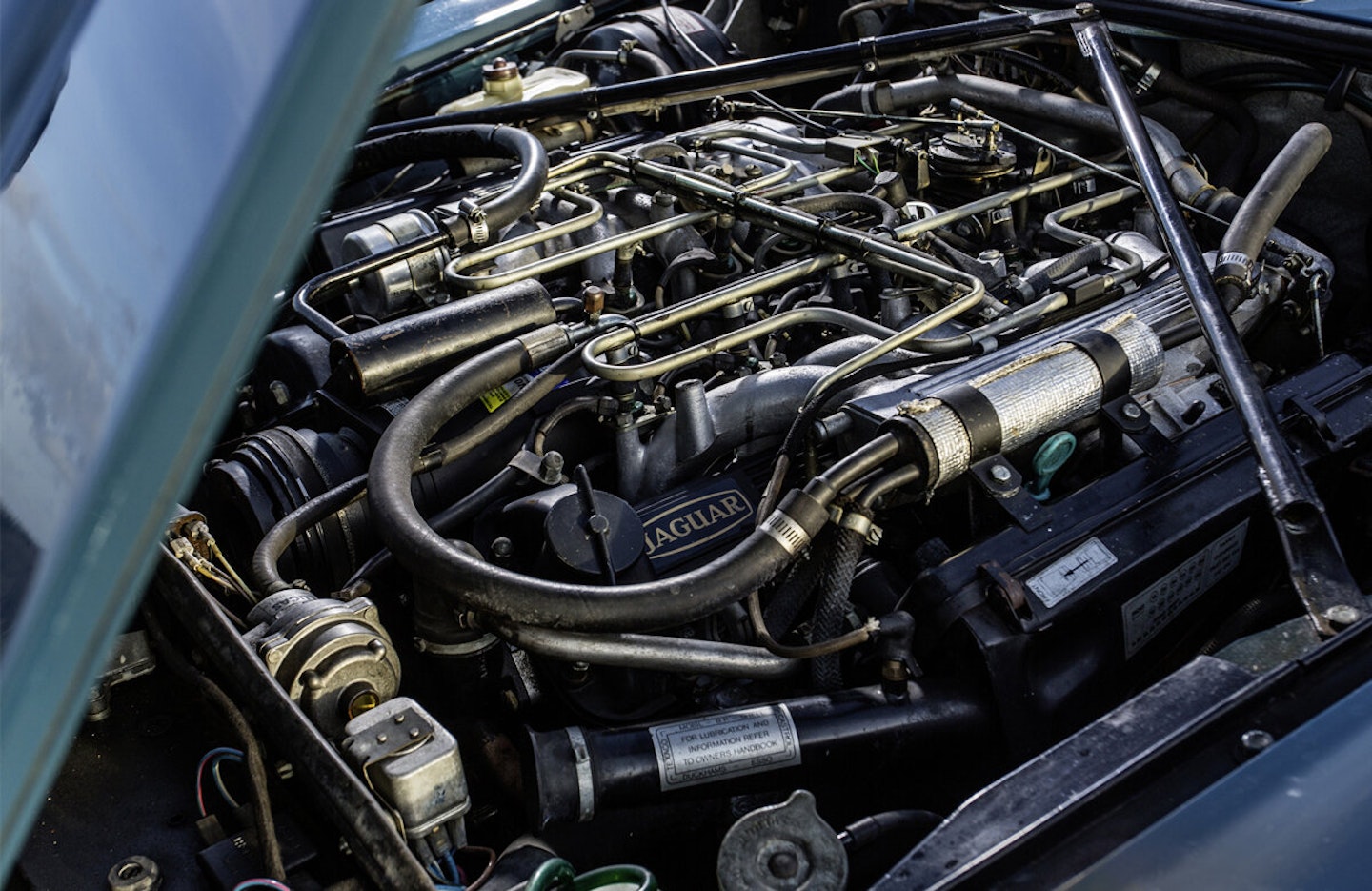

Total silkiness is the idea here. There’s 5.3 litres of V12 engine, in perfect reciprocal and rotational balance and with six firing pulses for every revolution. That obviously means six compression strokes for every revolution too, which is why the engine sounds as if it has no compression at all as I spin it on the starter. They all seem to merge into a continuous resistance.

On its 1968 launch, Jaguar’s XJ6 saloon redefined refinement in large, luxurious saloons, while achieving the clever trick of combining this with a strong and class-leading dose of dynamic flair.

Road noise was almost banished as those fat Dunlop SP Sport Formula 70s glided along the road, helped by hitherto-unseen levels of clever subframe isolation via rubber mountings, while the venerable XK engine turned more mellifluously than ever. However, nicely timed for the energy crisis, Jaguar had a new V12 engine ready for yet more serenity.

In prototype four-camshaft form it powered the never-to-race XJ13 sports racer, which famously barrel-rolled into the Motor Industry Research Association test track’s infield during promotional filming for the XJ12 saloon, powered by the production, two-camshaft V12 version. Walter Hassan, late of Coventry Climax (by then owned by Jaguar) and Harry Mundy, a former Autocar technical editor, designed the V12. Fuel efficiency was not its forté – about 16mpg is as good as it’ll get. But it made the XJ12 one of the most desirable saloons in the world.

Then the XJ got a facelift for 1973, with three body styles instead of one. There was a new, longer-wheelbase saloon, and on the original short wheelbase was now offered a two-door coupé whose vinyl roof covered up the joins in the thick rear pillars required to restore rigidity to a body now bereft of centre pillars. I can wind all the side windows down to make a completely open space above the waistline. It’s surprising how the pair of long, frameless doors, those thick rear pillars and the unexpectedly cosy rear-seat accommodation make this XJ feel smaller than it is; a proper ‘cut’ coupé, even though it isn’t. The cabin exudes a Jaguar-unique blend of luxury and mid-Seventies Leyland cost-paring, with a fine array of Smiths dials set in polished wood but a nasty upper-centre console of black vacuum-formed plastic housing a Dralon-lined tray and held on by crude screws.

By modern standards this is a simple cabin. And this 1977 car still smells quite new, which bodes well for the authenticity of the drive to come. The automatic gearbox has just three forward gears, and the overall gearing gives just 22.9mph per 1000rpm in top. That seems very short-legged by today’s standards, but there’s 135mph on offer here and a brisk 8.6-second 0-60mph time. The Jaguar doesn’t so much streak off down the road as gather pace, near-silently unless I goad the engine into revving out its smooth, seamless blare. It’s heavier than the Jensen and has, at a modest 240bhp, less power, but it feels faster mainly because the gearbox is more co-operative. Wieldier, too; helped by dampers obviously in the prime of life, the XJ12C is unexpectedly lithe and accurate in its response to my commands via precise steering which, while still light, is meatier than I remember from the last saloon XJ12 I drove.

Ride on the money

And that famed ride? Well… that damping has a light, deft touch to the way it holds the body steady over ripply roads, but when those roads are disintegrating in a way they did less in the Seventies, even this Jaguar suffers the odd clunk and thump. And I can feel that the body is less stiff than the saloon’s. However, this is still a car in which I can waft all day long on a wave of serene speed, on roads straight or sinuous. It’s delightful, handsome and rare with 1873 examples made over two years before the XJ-S rendered it redundant. Give me this over an XJ-S any day.

Citroën SM

Somewhere in a distant galaxy, human-like beings have developed a mechanised, electrified civilisation. It has taken some slightly different turns from ours. There, a car like a Citroën SM is normal.

There, it’s unremarkable to have a racy V6 engine half-buried in the bulkhead, the gearbox pushed out front beneath a long shaft extending right to the radiator to drive an alternator and an air-con pump. Four green spheres like these would float in every engine bay. Tying all these components in a web of wires and pipes, smothering the engine bay like the tendrils of a light-starved plant, would be entirely normal.

And why shouldn’t I change a wheel by oleopneumatically raising the suspension, supporting the car with a bar and then oleopneumatically retracting the wheel?

Come to that, why have a brake pedal when a large, rubber-faced mushroom does an equivalent job? Or more than one spoke on a steering wheel? And so it goes on and intriguingly on, in typical Citroën fashion. Look at that gearlever, which seems for all the world like an automatic transmission selector able to move only fore and aft, but isn’t. Next to that, the conventional handbrake is a surprise, although it’s strange to find the radio set sideways next to it.

What Citroëns of this era and earlier tended not to have, though, was an engine of equivalent exoticness. Not the case here: Citroën had taken over Maserati, and the Italian maker’s V6 – used also in the Merak – plays the exotic card very nicely indeed. It’s a 90-degree V6 (wider and lower than the 60-degree norm, but requiring split crankpins to give even firing intervals and acceptable smoothness), with three twin-choke Webers and a pair of overhead camshafts on each bank. It makes 170bhp and an identical amount of torque in lb ft, and drives the front wheels through a five-speed gearbox. Maserati muscle meets Citroën curiosity. Culture clash or marriage made in heaven?

Let’s find out. The way it looks gives a fair idea of what to expect. That smooth, glazed front, the covered rear wheels, the sills hidden away behind the bottoms of the doors and wings… all are Citroën design features made more menacing here by the angularity of the window apertures and the pair of exhaust pipes. Inside is a curved, hooded instrument panel with oval dials and a plethora of warning lights, including one very large red one that glows whenever any other is lit to denote a fault. It’s designed to grab attention, and it also does a disconcertingly good job of grabbing sunlight, causing spasms of worry while driving through a light-dappled forest.

The SM starts up with a gravelly growl. Its suspension rises on its oleopneumatic cushion, into first gear – the five-speed gate is conventional in action, if not looks – and we’re off. The SM is famous for its ultra-quick steering, full of the weighting deemed appropriate by the engineers but devoid of actual feel. A tyre could deflate and I’d hardly know. Drivers new to the SM found this unsettling back in the day, because it felt like nothing else, not even a DS.

Back to the future

Yet it’s not so alien by today’s standards of electric assistance. There are no steering electronics in the SM, of course, but the sensation is that of a modern electronically power-assisted steering car with a keen on-centre response. I get used to it quickly and enjoy the remarkable agility it bestows. It’s a similar story with the brakes, which respond more to pressure than movement but are powerful and progressive to a right foot used to modern cars.

This is one of the few classic cars that an average driver might find easier to drive now than he/she did back in the Seventies, simply because the way it drives is serendipitously aligned with the driving characteristics of today’s cars. The way the steering takes on several inches of play when the hydraulics are powered down is not mirrored in modern motors, though.

As for the ride and handling, both are very fine indeed. The SM smothers bumps with the nonchalant fluidity of a DS but without the heave and float when pressing on, and in a fast bend it just points and grips, feeling more natural the faster it goes. And fast it can go, up to 135mph thanks to those smooth aerodynamics, although 170bhp gives no more than brisk, rather than potent, acceleration. It does sound good in the process and not Citroënesque.

This is a fabulous car, and nothing like as scary as its reputation suggests. The surprise of the day? Undoubtedly.

Peugeot 504 Coupé

There’s a V6-engined one of these too, using that strange engine co-developed by Peugeot, Renault and Volvo as three-quarters of a stillborn, energy-crisis-scuppered V8, but the timewarp 504 Coupé here has the 2.0-litre, overhead-valve, slant-four fitted to most 504s after 1970. This 1978 car has the Kugelfischer fuel-injected version with a modest 106bhp driving, via a four-speed gearbox, rear wheels independently sprung by semi-trailing arms.

So far, so normal, apart from the fiendish complexity of that Kugelfischer four-piston injection pump with its own private oil supply. Now look at it. The regular 504 saloon is a bit of a frump, despite its trapezoidal headlights and curiously bevelled tail, but the Coupé and its Cabriolet sibling are gorgeous. All these body styles are the work of Pininfarina, but the pens and brushes roamed more freely with the glamour versions and the Torinese styling house also got to build them.

Look at the wide, shallow headlights. That curvy waistline, dropping between the front and rear pillars. The near-flat rear window contrasting with the sensuous flanks. It’s all very elegant, very understated, very silk purse from une oreille de cochon. True, the visual outcome is more Pininfarina than Peugeot but that doesn’t matter. People bought the Coupé in small numbers over a long production run, from 1968 right up to 1983. Later V6 examples were slightly spoiled by big, mutton-as-lamb bumpers painted in body colour, but our car here has the correct bright-metal adornment plus some quite fat alloy wheels as offered from the late Seventies. They wear fully-metric Michelin TRX tyres, of a devilishly hard-to-obtain 190/65 HR390 size. To keep the metric wheels is the mark of a true 504 Coupé enthusiast.

Inside this pale green car all is very brown, from chocolate through to autumnal leaf. Three round dials sit ahead of a brown steering wheel whose two spokes each contain a round hole intended to hint at a possible sporting spirit. This wheel seems set high, but that’s because I’m engulfed into the depths of an embracing seat trimmed in soft velour. Italian the Peugeot may seem from the outside, but its cabin is purely French. Apart, that is, from the pleated headlining, a feature found also in the Fiat and the Italian-styled Jensen. There’s usable rear seat space in here too, despite losing eight inches of wheelbase to the saloon.

Rugged relaxation

To drive, the 504 Coupé really isn’t a sports car. It’s more about being seen to cross a continent in relaxed, rakish style and being admired once at journey’s end. There’s an aristocratic bearing about this Peugeot, born of gentler, less go-getting times when people accepted and enjoyed style for what it is instead of obsessing over brands and peer-group pressure. That’s not say this 504 isn’t an enjoyable steer: it is.

The engine has the relaxed torquiness expected from its low specific output, delivered willingly if not particularly smoothly or sonorously.

It’s more propulsion device than aural feast, but the precise gearchange helps make the most of the modest but affable performance. Where this car does score, though, is in its ability to cope with bumps and dips while steering an accurate course. Peugeot has long had a reputation for an outstanding blend of ride and handling, albeit one that took a bit of a beating in the early noughties and is only now resurfacing, and this 504 Coupé is true to type as befits its role as a handsome cruiser.

Remember, too, that the 504 family won the world’s toughest rally, the East African Safari, on two occasions and did likewise on other African events: this is a strong, solid, well-built car. Those who regard Peugeots as flimsy have short memories.

You’ll be lucky to find a 504 Coupé or Cabriolet for sale in the UK – they were never made in right-hand drive nor sold here. They are also more Italian than French in their rust resistance. However, it’s worth tracking one down in mainland Europe, as happened with this example, and bringing it back. There has probably never been a more understatedly glamorous Peugeot.

BMW 3.0 CSi

Everyone loves the BMW 3.0 CSL, especially in its homologation-special ‘Batmobile’ guise. Thin, lightweight panels, fatter wheels, a general air of race-honed purpose overlaid with an exuberant straight-six howl… how could anyone resist that concoction?

In truth, though, the 80kg or so it shed relative to a regular 3.0 CSi brought its own problems. Rust was the obvious one, owing to a lack of undersealant, a floppier body structure was another, and the ease of denting the aluminium opening panels was a third. Maybe a CSi makes a better, more usable road car. That’s why this fine red example has joined our group test.

Visually, this red one isn’t far short of a CSL anyway. Its Alpina wheels are similar to the CSL style, albeit of 16in diameter rather the BMW’s original 14-inchers. And it even has the deep front valance normally fitted to a CSL only if someone had broken into the box of homologated racing bits that might have been delivered to the first owner. In standard road trim the CSL didn’t wear that front spoiler, although its wheelarches were racily extended with brightly polished aluminium lips, and the upper flanks wore go-faster stripes.

Our car looks low, mean and ready for a spirited blast on a B-road. It’s the most overtly sporty-looking car here, and the only straight-six. That’s somehow fitting, because in today’s world of new cars BMW is about the only carmaker left that still builds straight-sixes.

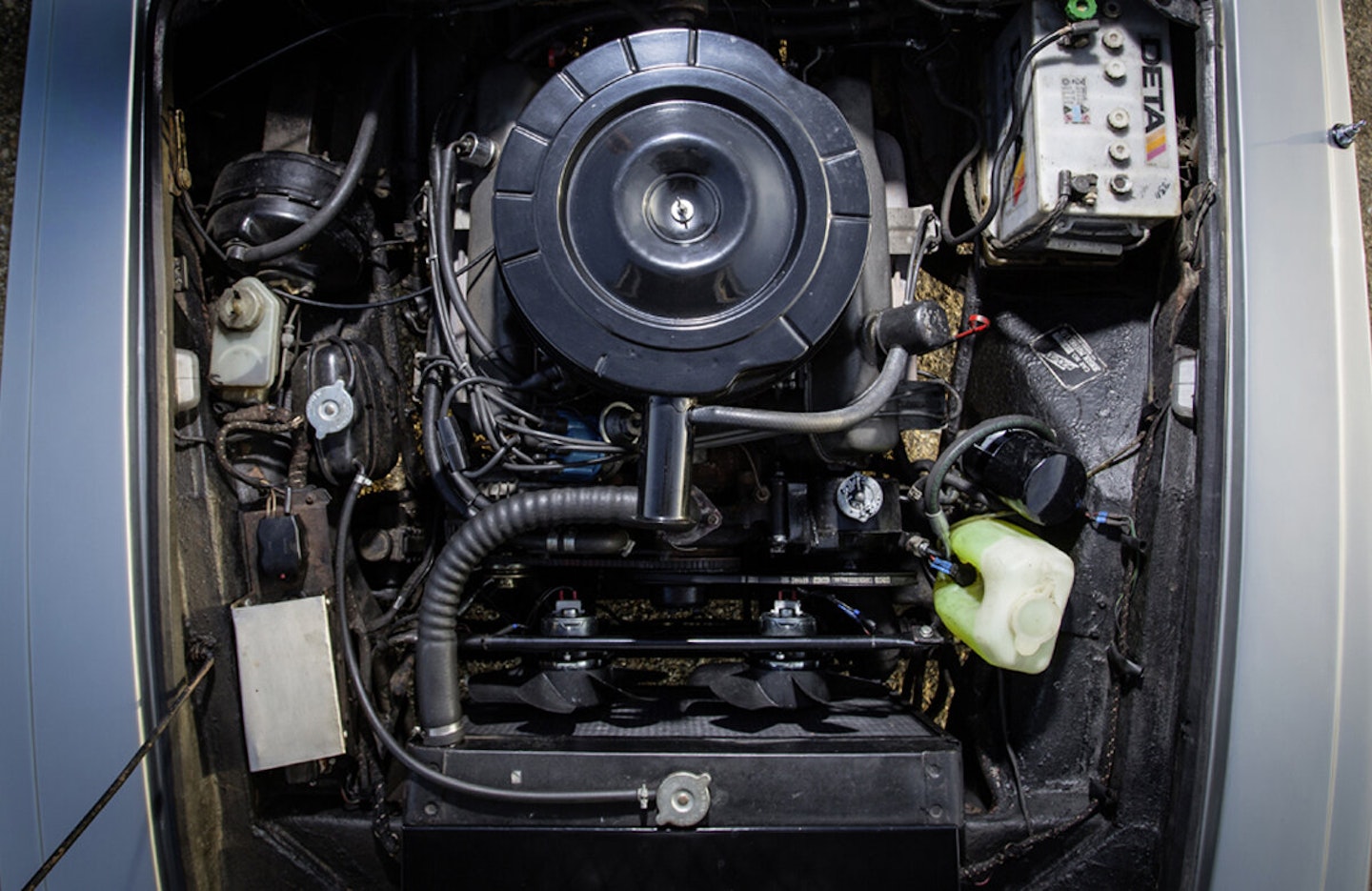

This BMW’s a delicious-looking device, all slim pillars and glinting highlights, with a tantalising air vent in each front wing and an air of slight menace missing from the first versions of BMW’s Karmann-built CS models. Under the bonnet is a 2985cc fuel-injected version of BMW’s M30 sohc engine, a family that had started at 2.5 litres and eventually reached 3.5 litres, lying inclined beneath a giant cast-aluminium plenum chamber from which six inlet tracts do a U-turn en route to the cylinder head.

I love BMW interiors of this era. They are open-plan and airy, with a delightful no-nonsense functionality. This is one of the best, with a dashboard consisting simply of a full-width shelf on which sits a four-dial instrument pod. This and the curved, vertical panel between windscreen and shelf are faced in stain-finished wood veneer, an unnecessary embellishment but a typical Germanic take on tree-use; it continues along the doors. A wide, squat console sits beneath, as does a glovebox on the passenger’s side. Rear seat space is minimal for anyone with legs.

In place of BMW’s standard three-spoke steering wheel is a Moto-Lita item, slightly smaller and thicker of rim to match the extra bite of this car’s wide, 225/50-section Pirelli P7s. This is the first car we’ve covered so far in this test to have a worm-and-roller steering box rather than a rack, although the Mercedes and the Fiat also use a similar system. It takes just a couple of quick bends to show that it doesn’t matter at all.

Palpable precision

I take aim, feeling the front wheels bite into the corner like a good hot hatchback’s, point that wide, flat bonnet with its pointed snout at the apex, feel the loads build up through hands and posterior, and power through in archetypal taut-sinewed, rear-drive fashion.

The steering’s fractional softness around the centre vanishes as soon as there’s any semblance of lateral g-force, replaced with a precision and transparency I didn’t quite expect. There’s no power assistance but nor does there need to be, despite these broad boots. Manoeuvring is the only time a driver might yearn for it.

The seats are very supportive, holding me well as I thoroughly enjoy the CSi’s energy, helping to damp further an already calm, disciplined ride.

And the engine? It feels smooth but a touch dozy at low revs, then comes to howling, joyful life as the tachometer needle passes 4000rpm and I realise that 200bhp really does live here. This BMW will touch 60mph in well under eight seconds (a CSL scores 7.2) and reach an honest 130mph, with a revability well beyond 6000rpm to make up for having a gearbox with just four forward ratios.

Of all the cars here, the BMW feels the most modern in the conventional sense, even though others are newer or more forward-looking.

It’s the most fun, while likely to prove durable and dependable. Still want that fragile, expensive CSL?

Mercedes-Benz 450 SLC

Is it an SL with a hardtop? Or is it something different? I do a double-take when I see the SLC.

It’s not just the lack of a join between waistline and roof. There’s that extra 13in of wheelbase between the rear edges of the doors and the rear wheelarches, and what looks like a partially closed, pleated curtain towards the back of the rear side windows. Never mind the bigger rear window, gracefully curving into what could be called the C-pillar if only there were a B.

Meet the Mercedes-Benz SLC, the only Benz fixed-head four-seater coupé to be based not on a saloon but a roadster. It’s an intriguing design hybrid, an idea almost without precedent apart, arguably, from Jaguar’s E-type 2+2.

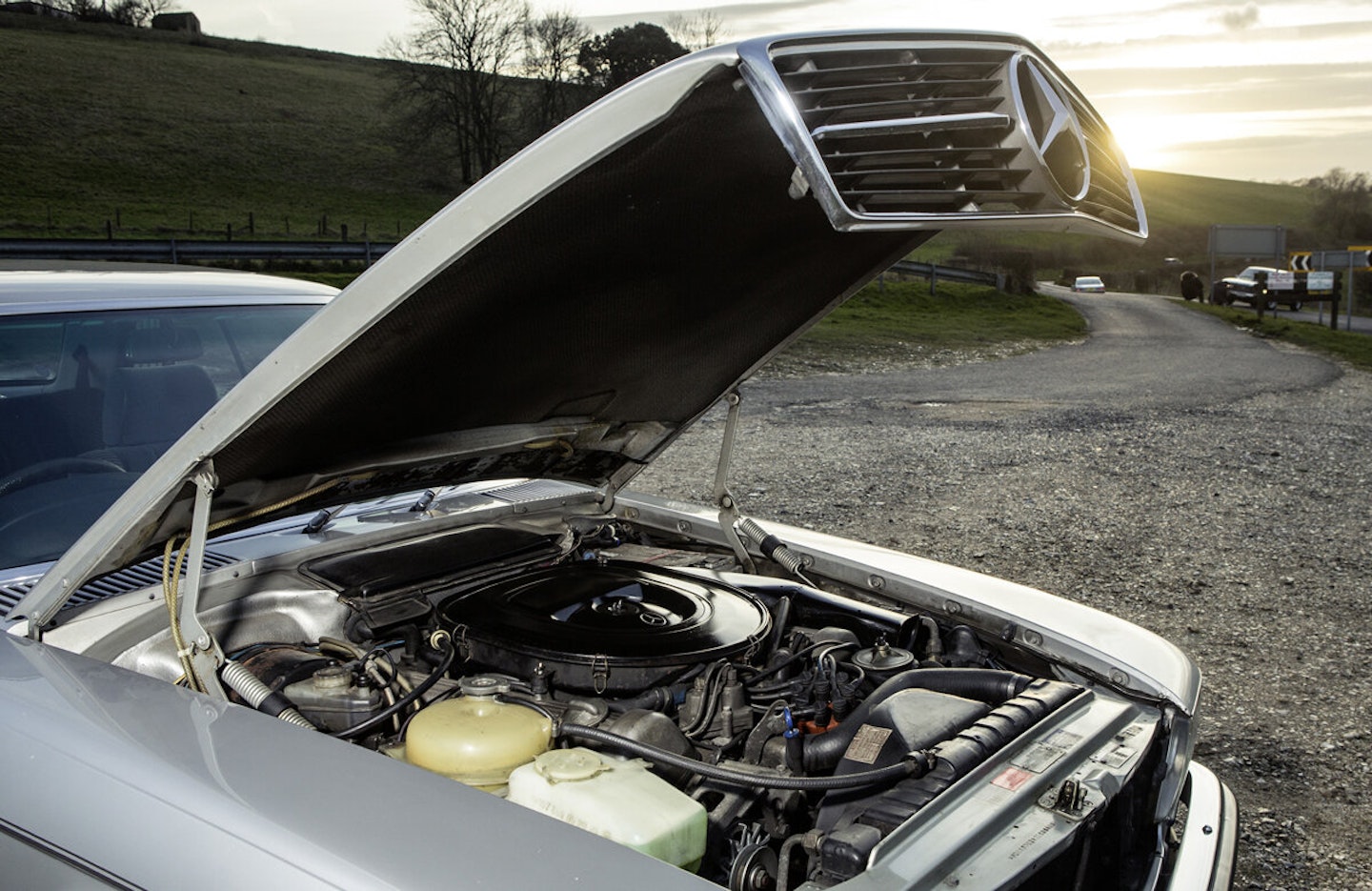

In those far-off days, Mercedes-Benz model numbers really did, with a few exceptions, reflect a car’s engine capacity. So an SLC could be had as a 280, a 350, a 380 or – as here – a full-fat 450. There was also a 450 SLC 5.0 with a different, aluminium-block V8, but that’s a rare beast indeed. So our 1980 450 has a 4520cc engine with an extraordinarily lazy 225bhp and a could-try-harder 279lb ft of torque. A highly-strung racer this is not.

Nor, really, is the Merc even a sports car. It goes further down the road of relaxed boulevardier travelled by the R107 SL, and there’s nothing wrong with that judging by the R107’s popularity over an extraordinary 17-year production run. So the transmission is a three-speed automatic, the steering wheel is vast and the broad seats with their stripy velour trim feel as though I’m sitting on a single piece of lightly padded, coil-sprung plywood. That’s how Mercs of this era are. They were also beautifully built, with luscious attention to detail and an air of indestructibility. The dashboard has shades of a Merc saloon’s, sportified only by recessing the three dials deep into separate tunnels in the binnacle beyond the padded-boss steering wheel, and setting a trio of round vents into the centre of the dash under individually shaped cowlings.

Before we waft off down the road, we’ll take in some of the SLC’s many design niceties. First off, those rear side windows. What looks at first like a pleated blind is in fact a series of angled slats able to let some light slip through. The slats are sandwiched between sheets of glass, the whole ensemble about an inch thick, a sealed unit seemingly impossible to renovate should the worst happen. They are there so the main rear side window can be shorter, and thus wind fully down into the rear wing without tangling with the wheelarch. Thus retracted, along with the frameless door windows, the SLC becomes a fully pillarless coupé.

Then there are those rear lights and front indicators, the first to use the ridged theme later universal on Mercedes-Benzes. The idea is that even when covered in road dirt, they can still emit a useful amount of light. More striations adorn the lower flanks. The wide front grille is attached to the bonnet, so I have to be careful not to bang my head on it when administering to the densely packed engine bay.

It may share its nationality with the BMW but the driving experience could hardly be more different. In place of the crisp-edged, eager revvability and high-definition dynamics comes a lazy surge of effort and an exquisitely unflustered, leave-this-to-me demeanour.

Smooth surge

The SLC is usefully fast but it’s chill rather than thrill, guiding the prow smoothly through the bends, insulated from the bumps, feeling that prow rise up when I goad the engine into vocalising its distant V8 beat. As a tourer it’s pretty grand, and it leaves my mind to think about other things as I whisk along serenely.

This is modernity and capability of a different sort, crushingly competent and very Mercedes-Benz; of all the frameless-door coupés here, it has by far the least wind noise. This car shrugs off its 24 years as though time barely matters, but it does have a more organic feel than I’d get in a modern, microprocessed SL.

It is, in short, utterly charming. And so, so cheap now for what you get.

Fiat 130

Received wisdom has it that the Fiat 130 Coupé is a beautiful car. It was designed at Pininfarina by Paolo Martin, whose attempt at a similar theme for the Rolls-Royce Camargue is the Mr Hyde to the 130’s Dr Jekyll. So, in retrospect, is the 130 Coupé an object of pure beauty with its wide, flat headlights and the subtle dihedral of its flanks? Or is it, actually, a bit naïve and heavy-handed, an outsize caricature of something more lissom?

It’s certainly larger than life, longer even than the Interceptor although not as lengthy as the SM whose tapered extremities disguise the size of its roadprint.

One welcome side-effect of this vastness is that there’s more rear-seat space in the Fiat than in any other car here. This is a family-size four-seater that just happens to have two doors.

Contemporary tests drooled over the Fiat’s plushness. Motor again, ‘Inside, it’s not just lavishly equipped but exquisitely finished and appointed. We can’t recall anything finer in style and décor, regardless of price.’ Wow. And a Fiat too. Eat your hearts out, premium brands.

It’s true that the interior is pretty special, melding the feelgood traditional warmth of wood veneer and sumptuous, pleated cloth-and-leather seats with an arresting design-house modernity.

There are lots of bold, straight lines mirroring those outside, and the sort of in-your-face diagonals much loved by Italian designers: I see them on the door trims, and most strikingly in the black slatted grilles covering the doors’ loudspeakers. Then there’s the steering wheel, here with three holes in each of the two spokes instead of the Peugeot’s demure one, a broad, switch-filled centre console and an instrument panel that would really need only a single sheet of curved Perspex covering it to make it something from a car 15 years newer in design.

For 1971, the Coupé’s first year of production despite the numberplate seen on the car here, it was quite a revolutionary dashboard. It’s all the more impressive, then, that the dash design is one of the few styled features shared with the 130 saloon, launched two years earlier.

Worthy rasp

Under the Fiat’s striking skin lurk entirely worthy mechanicals. The suspension is by struts all round, sprung at the front by torsion bars to make room for the broad, albeit 60-degree, V6. The engine, designed by that automotive maestro Aurelio Lampredi, shares its belt-driven overhead-camshaft architecture and detail design with the humble, four-cylinder Fiat 128 unit, but everything is suitably upsized to create a 3235cc capacity and a 165bhp power peak.

Air and fuel pass through a single, twin-choke Weber carburettor, and peak torque of 184lb ft arrives at a gentle 3400rpm despite the astonishingly oversquare bore and stroke dimensions (102mm and 66mm respectively).

However, there are 1610 kilograms to haul and only three automatically-shifting, Borg-Warner-machined gears to do it through. No wonder the 130 Coupé has such short gearing; at 80mph the engine is spinning at over 4000rpm, hardly fitting for a luxury tourer. So it proves to be a slightly schizophrenic car to drive, with a relaxed, supple ride, languid power steering requiring larger wheel movements than a powered system should, but an engine which feels racier than its surroundings allow it to be.

It has a typical V6 note, like that of a straight-six but with an underlying ripple, and it likes to rev beyond its refinement zone so it can be heard. Its best efforts result in a 116mph top speed and a 10.6-second 0-60mph time according to that Motor test, neither figure particularly impressive, while our test car’s spongy, long-travel brakes appear to mirror those of both test cars tried by the weekly magazine’s testing team back in 1973.

I can persuade the Fiat to fly if I make maximum use of the rather violent kickdown, but that’s when decorum deserts it and its innate Italian fizz surfaces.

Of all the cars here, the Fiat is the most curious. It looks dramatic, it oozes Italianate luxury from every surface and it has a Lampredi-designed V6 under the bonnet. However, the engineers never quite finished honing the way it drives.

This would be a fascinating car to own, not least because it’s so rare. But as a companion to take on a transcontinental trip, I’m not so sure.

Lancia Gamma

Aldo Brovarone was the main designer at Pinnfarina in the Seventies when the Lancia Gamma was under creation. What Lancia didn’t know, as it launched the Gamma Berlina in 1976, was that – while assisting with the saloon’s shape – Pininfarina had been secretly working on a coupé version built on a 4.5in-shorter wheelbase, which duly appeared at the March 1976 Geneva show. In a display of on-the-hoof product planning unthinkable nowadays, Lancia said ‘okay’. By the autumn, Pininfarina had put the Coupé into production.

It retained virtually all of the concept-car looks of the show car and it really is a handsome machine, with its scooped-out flanks and strong, straight lines including the flat-topped, lipless rear wheelarches. Then there’s the central dip in the bootlid, flanked by gently angled slopes out towards the edges of the rear wings, and the hoop formed by the rear pillars to suggest, with false promise, a targa top. The whole car is a fabulous piece of surfacing, of sheet steel given taut, metallic life with just enough curvature at the bases of the window openings to move it beyond the merely mechanical. It’s a much more sensuous-looking car than the rectilinear Fiat.

It’s also the last Lancia-engined Lancia. The engine shares its flat-four configuration with the smaller, earlier Flavia but it was an entirely new unit, now with an overhead camshaft for each bank instead of pushrods, and both cylinder block and heads cast in aluminium. Drive is to the front wheels via a five-speed gearbox, a feature that is shared only with the Citroën among our cars here.

Defeating convention

Motoring folklore piles various troubles onto the Gamma, but they don’t apply here. The body has no rust, the lubrication system is fully sorted and the power steering pump is no longer driven from the left camshaft, so there’s no danger of a jumping cambelt and consequent mashing of valves should full lock be applied when the engine is cold and the power steering fluid is thick. With that out of the way, we can learn more about the Gamma’s inner secrets.

Its engine, large for a four-pot at 2484cc, delivers 140bhp and 153lb ft of torque, and did so whether on the original Weber carburettor or, as here, on Bosch L-jetronic fuel injection. Its suspension follows that of the smaller Beta in featuring coil-sprung MacPherson struts all round. The interior doesn’t match the Lancia’s exterior for sculptural intrigue. It’s plasticky, a bit flimsy and the instrument and switch binnacle sits so high that it spoils the chance of a panoramic view forward. I like the angled door-pulls, though.

Contemporary road tests praised the Gamma Coupé’s steering, ride and handling, describing how in the right circumstances it was even possible to get it to oversteer under power. I don’t manage to persuade our metallic light blue example to emulate its predecessor, but it does handle tidily with the front end’s low centre of gravity no doubt playing a part. There’s a degree of dashboard shudder and choppiness up front over bumps that I don’t remember from the last Gamma Coupé I drove, but I suspect this car’s front struts may be past their best.

What is not in doubt is the characterful nature of the engine. Lancia’s hopes that it could compete in refinement with a V6 were unrealistic, because for all its mechanical balance a flat-four’s chance of smoothness is scuppered as soon as it’s under power. With bangs happening at four corners it could hardly be otherwise, and the beating exhaust note doesn’t help its case. But in itself it’s a great sound, and there’s a strong barrel of torque to dip into here if I’m not after realising the potential 9.4-second 0-60mph time and 120mph top speed. And, given the loose, rubbery, gritty uncertainty of the gearchange, that’s no bad thing.

But in the end the Gamma suffers that Italian-car problem again, that ability to swing unpredictably between endearing and infuriating. Like the Fiat, the Lancia was not fully developed, honed, calibrated and civilised before its engineers signed it off. The Gamma Coupé could have been one of the world’s most lusted-after cars if they’d done a proper job.

As it is we can just admire, and wonder what might have been.

Our coupé of choice?

You could own any of these cars and love the experience. It needn’t break the bank, either, with an excellent Gamma Coupé obtainable for around £6000 and a Mercedes SLC for not much more. True, you could pay up to five times that or more for the most valuable cars here, but that’s still well below the prices charged for their nearest modern counterparts.

As an affordable way of travelling in a style no longer subject to the spectre of depreciation, any of these cars fits the bill. But which is it to be? The Jaguar and the Mercedes vie with each other for maximum relaxation and waftability, with the British car a touch more engaging and the German one likely to be less demanding of attention. The Italian coupés ooze style, as expected, but are better gazed upon than driven an extended distance.

At one extreme of engine size we have the Jensen, the oldest design here although it certainly doesn’t look it. At the other end of the scale, with an engine less than a third of the size, is the Peugeot whose performance is modest but whose demeanour is as delightful as its styling. The French car is ultimately the more capable, more ‘balanced’ drive but I have to love the Jensen’s hot-rod bluster.

Our two favourites here, though, are the BMW 3.0 CSi and the Citroën SM. Initially the BMW is easier to like for being more conventionally invigorating, with an inspirational engine when given its head, very engaging handling and fabulously elegant, crisp looks. There’s also the glow of knowing you have, in usability terms, a better car than a CSL at much less cost. It’s almost irresistible.

But when I drive the Citroën, I realise what an other-worldly feat of engineering it is and how well it works. It’s quick, it sounds great, it rides beautifully and it handles in a way that’s barely believable, thanks in large part to that prescient steering. Far from being a reason to be scared off, it is one of the main reasons to have an SM. And that’s even before we discuss the looks, other-worldly like the engineering, and the sci-fi interior. Citroën SM. Think of the good times you could have in one. You know you want to. We certainly do.

Thanks to Goodwood Motor Circuit for the opening spread photograph location, Munich Legends and the Jaguar Daimler Heritage Trust for the loan of the BMW and the Jaguar respectively, all the owners and their respective clubs, and Club Peugeot’s Gary Charlton for much additional help during the day.