The Lamborghini Espada exudes exotic elegance in standard form, but not all cars were created equal...

Extravagant. When I drive an Espada, I can’t get that word out of my head. That and a load more luxuriant superlatives, as well as a buoyant feeling of rakish indulgence, a School for Scoundrels admittance that I really was born to be a cad. Was that a speed camera flash? Hope it got my good side.

I think the feeling is encouraged by sitting so low in such a wide and powerful car. There’s that sense of prowling the road, with the engine’s muted growl resonating deliciously through the cabin. It rolls around your legs and, with a kick of the side of your foot on the down-changes, flourishes into a snarl.

The air of luxury is enhanced by the fact that this very car was graced by none other than Princess Grace of Monaco, who drove parade laps around that principality’s famous Grand Prix circuit with her husband Prince Rainier in 1969. More of the Mediterranean royalty connection later, but if you were an upright English chap – maybe the Bentley Continental type – for whom this was your first foray into big exotica, the seating position might raise an eyebrow.

The car is Mercedes S-Class long (15ft) and Countach wide (6ft). But it’s only a hand’s span taller than a Ford GT40, so to climb in I find myself doing the same limbo-dancer shimmy I do to get into all the other exotics, big doors notwithstanding. It’s best not to fight it; simply abandon well-mannered rectitude and just slouch into the driver’s seat with a Latin disregard for posture.

Command centre

From this nonchalant, splayed-knees-higher-than-my-backside position, I quickly come to realise that I can control the big sled very well, sensing the big V12’s power spool up from seemingly nothing and the firm, taut accuracy of the steering.

The steering in early Espadas is unassisted, but above 3mph it’s no impediment, the big car responding immediately to its wheel – one up on most of its ilk. That wheel has a slightly more horizontal angle than most, you can even steer with a modest push or pull at the elbows to change lanes on faster roads, the car flat and steady.

Like the steering, the power flow from the big V12 is silky smooth. It takes hold surprisingly low down in the rev range, the engine’s tone a low, hollow grumble with the faint flutter of the fuel pumps. Then, as my foot goes down on the throttle, a deep, basso-profundo bark rises as the car’s thrust builds, turbine-like, giving way to a tenor growl, overlaid as the big tachometer needle climbs around its dial by a singing, metallic exhaust note. It’s earthily mechanical, yet refined. You feel an immense poise at the centre of the storm.

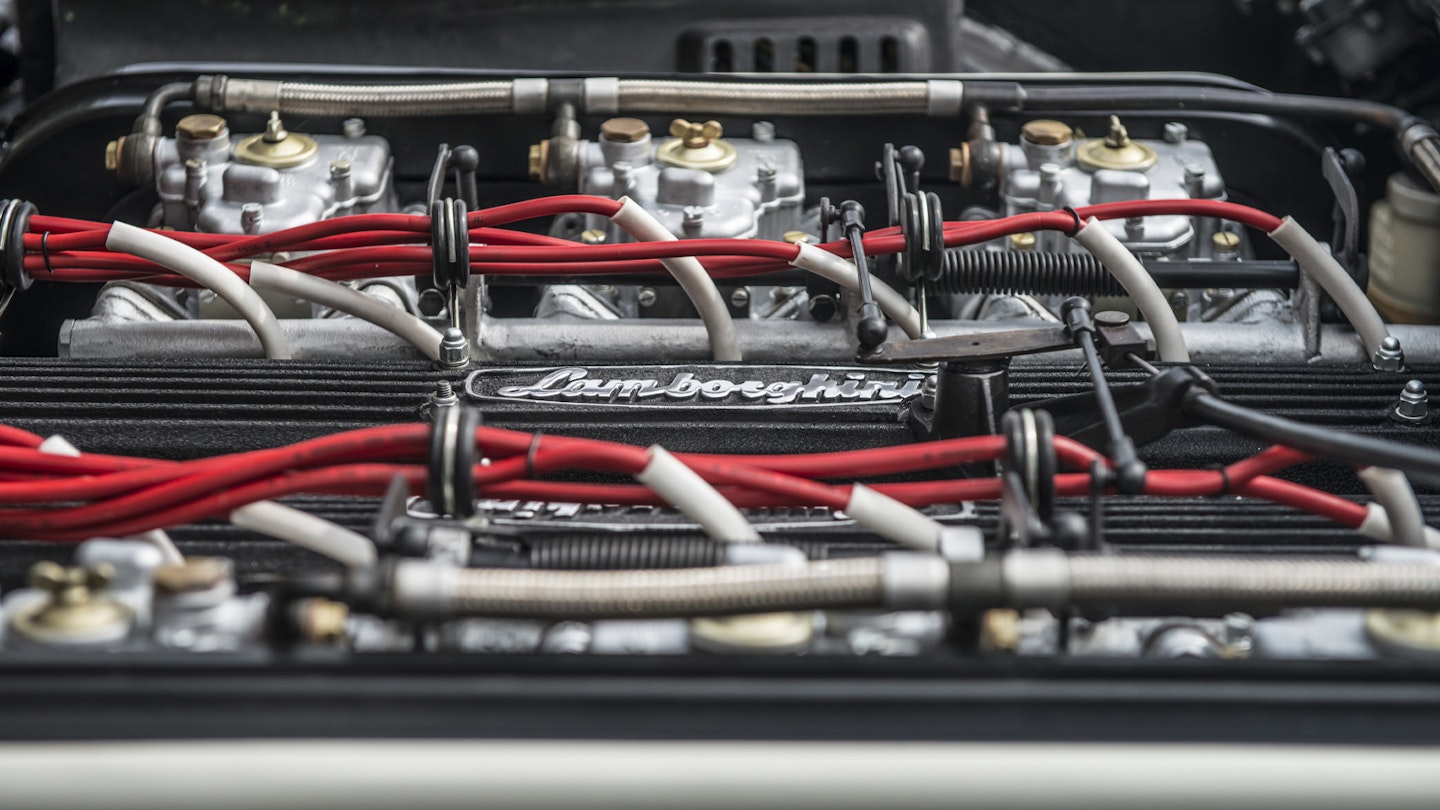

The valve-train clamour or induction roar of the similarly-engined Miura is absent, but the engine in that car is only inches from your shoulder and configured as its creator Giotto Bizzarrini had intended, with rorty downdraught Weber carburettors. In the tourer, the motor is laid out flat and wide under that huge bonnet, with side-draught carbs and gearbox behind.

A sensory experience

The Espada weaves a very rich spell on so many sensory levels. Inside, everything seems to have an overtly aesthetic function; the square-shouldered stacked-polygon instrument pods (not unlike some of the concrete architecture of its day) separated into tiers of functional importance, and the lines of the sweeping centre console tapering and funnelling the visual momentum through the car.

The Espada is, of course, a GT – just cast your eyes around that low-slung, open-plan cabin and they’ll alight upon proper rear seats. They must have used a whole extra cow’s worth of leather to trim them. And it is, to all intents and purposes, a hatchback.

This particular example, chassis 7293, has something to make it the envy of all its class – a full-length Plexiglas sunroof. It transforms the driving experience, making the car feel almost transparent as sunlight and the shadows of clouds flow over my arms and body and through the cabin. It gives me an idea of what it must have been like to drive the Espada’s not-too-distant cousin, the Marzal concept car, which had both a glass roof and glass doors.

Apart from both cars being designed by Marcello Gandini, the Espada and Marzal have something else in common. And this is where we return to the Mediterranean monarch connection, because the Marzal was driven around the Monaco Grand Prix circuit as an honorary course car in 1967 by Prince Rainier, with Princess Grace at his side.

In 1969, when he did the same in 7293, he had the 11-year-old Prince Albert and his sister Caroline in the back –

and what better way to demonstrate that it was a family tourer?

A true great

Chassis 7293 had originally been custom-ordered by Franklin Davis, owner of Wynn’s Car Care products in the US. In a bespoke blue metalflake metallic (the same as the one-off Miura Spider), it was to be used to promote the Wynn’s product range.

But before being flown out to the States on an Alitalia cargo plane, Lamborghini wanted the car to perform a little promotion of its own – for the new Espada range. And so it appeared on news reels around the world, touring Formula One’s most glamorous Grand Prix circuit, in the hands of probably Europe’s trendiest royal family.

Isn’t that the epitome of the Espada experience? It’s certainly a car that befits a monarch with a film star wife, who ruled the world’s most fashionable tax haven from a pastel-coloured palace high on a rocky crag. But if you condemn this or any other Espada to a life simply as an ephemeral appendage, the significator of a ‘lifestyle’, then you have missed the point of one of the classic car greats.

Perhaps the Espada has itself to blame; its huge physical presence, the width emphasised by headlights at the farthest edges of the grille, the length accentuated by the upward sweep of the rear windows. And all that seemingly never-ending glass. Surely it was all too close to a show car to have any substance? But that is the ultimate fabulousness of the big Lamborghini – its performance delivers on the promise of the looks.

Beating heart

At its heart is a motor that fused the racing aspirations of its designer, ex-Alfa Romeo/Ferrari engineer/test driver Bizzarrini, with the fresh inventiveness of its young development engineer Gian Paolo Dallara. The then 3.5-litre V12, as initially designed for Lamborghini’s 350GT of 1963 drew on Ferrari traditions; the forward offset of the right-hand cylinder bank, a 77mm bore size (as in the Ferrari 400 Superamerica of 1960, and in Carlo Chiti’s experimental engines of the early Sixties).

Unlike contemporary roadgoing Ferraris, it had a twin overhead-cam design, allowing for sustained higher engine speeds with greater reliability. These were driven by separate triple-roller chains powered by half-speed gears driven by the crank nose. The drive layout was also copied from Carlo Chiti – his 1961 F1 Ferrari V6.

These were meticulously-built motors. It took 23 hours to adjust and balance each block, 30 hours for each of the crankshafts and 144 hours for each cylinder head. The engine was then put through a 20-hour test – ten hours run electrically, then a fuel-driven cycle under increasing loads.

Out on the road I’m feeling the profound character of this engine (now four litres). Heretical though it may be, it feels smoother than its Ferrari rivals. And it seems to have a grip on the whole car. Maybe it’s the higher compression ratio, lending a punch even at the lowest revs, allowing it to slow and dip below 1000rpm in fifth and yet saunter back up to speed without choking. You feel the engine braking in gearchanges with the nose dipping on the overrun.

Renewed vigour

I find it easy to set the Espada up for bends, going in on a lightly trailing throttle, the weight coming slightly forward, a slight lean to the outside rear haunch, before lining the car up with the apex and feeding through the power. And for all the car’s drama, you always feel supremely confident of the balance and communication between it, the suspension, the drivetrain and you.

This is the life these big GTs should lead, sweeping through forests and mountains across Europe, not kept in shadowy collections in enforced mechanical retirement. And some have endured even more cruel fates – when the appetite for space-age style waned, many Espadas fell on hard times, gas-guzzlers made even less popular by successive fuel crises and constantly-bankrupt Lamborghini’s erratic support.

Bought by many who could afford little beyond the thrill of their purchase, badly maintained examples were viewed as a monstrous liability, their values nowhere near the cost of the remedial maintenance required to bring them back to life.

Thankfully, collectors and enthusiasts are now looking at this period with fresh eyes. The Bertone Espada and Ferrari 308 GT4 Dino as well as Pininfarina’s 365GT/4 are making their way back. And rightly so. Still, I think this immaculate and unique version of an Espada Series I (which ran to only 186 examples) is still £100k adrift of the value it would boast with a prancing horse badge and a few more curves – and that is with build documentation and unrepeatable film-documented history.

Blended family

With its intoxicating blend of avant-garde styling, multi-timbred mechanical song, responsive handling and sheer quarter-miler grunt, Lamborghini’s full four-seater amply acquits itself as a very useable, versatile and exciting classic. It’s rare to be able treat the whole family to an outing inan exotic (whether they want to or not), and seldom do you get the chance to pack a picnic hamper and still be able to enjoy a V12’s howl on the way through the countryside.

Grand Tourer is a romantic term that we love to invoke in the classic car world, declaring that this or that machine would be a fantastic car to drive down to Geneva, Rome or wherever. But in reality, after half a day in many of those cars you’d be ready to shoot either it or yourself. I’ve driven down to southern Germany to meet this car. I’ll be going back via Stuttgart, Metz, Reims, Calais and then half the length of England. Would I choose to do that trip in this Lamborghini? In a heartbeat.

This article originally appeared in the May 2015 issue of Classic Cars magazine; click here to view the contents of the latest issue.