Maserati’s Khamsin was a concept car for the road. But decades on, how does this futuristic supercar – in unrestored form – feel on modern roads?

The driver’s door shuts with a solid thunk that refutes the lazy stereotype regarding Italian build quality.

Sat in the Maserati Khamsin’s vibrant blue interior, ahead lie green-on-black Veglia Borletti dials with more on the centre console, set amid an ergonomic riot of switches, slide controls, vents and knobs.

The dashboard’s stilted, blocky structure, edged in blue leather and trimmed with grey alcantara, is archetypal sportivo Seventies Italian and contrasts with the bold, swooping coherence of the exterior. The front seats are creased in places and their unusual colour worn away – providing proof of age and mileage – while behind are a pair of vestigial seats and a generous boot. The seat is comfortable, the adjustable driving position is spot-on and the footwell, thanks to this automatic’s two pedals and a footrest, is spacious enough to accommodate chunky brogues.

Mention the Citroën-era Merak, Bora or Khamsin and aficionado opinions are often mired in the notion of diluted pedigree; how Maserati’s Parisian owners had apparently imposed their eccentric engineering theories and practices on one of Italy’s great sporting marques between 1968 and 1975.

‘Slipping between ratios only seems to add to the sense of effortless ease and its optimistic modernity’

Yet, on our Italianate location – in reality, Denbies Wine Estate in Surrey – personal indifference toward the Khamsin has undergone a Damascene conversion. Gleaming in Argento Auteuil Metallico this beautiful first-rate, low-mileage Tipo AM120 Khamsin has finally made my eyes see what Maserati always intended. It has of course had bits ’n’ bobs fettled, it has not been stripped and totally restored. The preservation of its original ‘Made In Modena’ assembly elevates further the desirability of what is already an extraordinary machine.

Silver is certainly the Khamsin’s colour. Sat on understated 7.5J Campagnolo alloys and sporting a delicate blue coachline – echoing the leather interior’s colour – this Maserati looks infinitely better in the tin than in gloomy period photos. Move in closer and the Khamsin’s wedge is subtly augmented by striking details – gentle curves in the profile of the bonnet, the kicked-up tail and its detail line; the daring, asymmetric bonnet vent; that razor-sharp shoulderline; a neat rear bumper assembly mounted above a quartet of proud exhausts; and those rear lamps magically floating in the nothingness of its transparent rear panel. It’s all presented without tarnish, clouding, fading, flaking, lifting or perishing.

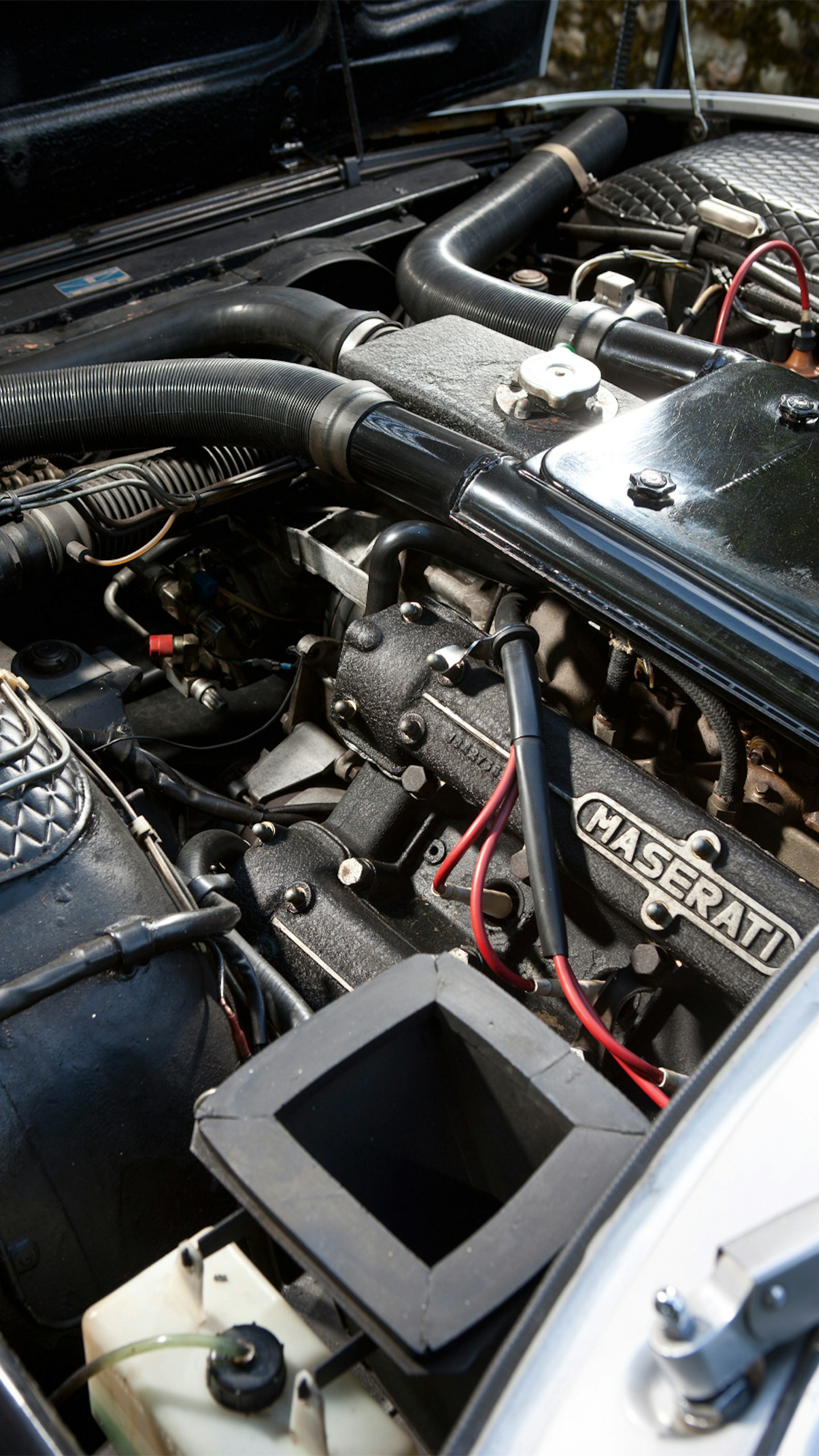

The Khamsin is the only production Maserati to have been completely engineered under Citroën. Unveiled at the 1972 Salone di Torino as a Bertone prototype, the Tipo AM120 was the first front-engined Maserati to abandon

de Dion rear suspension in favour of an all-independent design. Accompanying its Salone debut was a press release from Carrozzeria Bertone SpA that broadly translates as, ‘Based on a rational mechanical layout, Bertone could work absolutely naturally, creating a clean body surface, even if featuring highly distinctive and refined elements.’

Contrary to popular thought, this range-topping Maserati’s adoption of Citroën technology was not at the insistence of Maserati’s new French owners, but because engineering chief Giulio Alfieri was something of a Citroëniste. During an interview with Adolfo Orsi Junior, in Marc Sonnery’s opus Maserati: The Citroën Years 1968-1975, he revealed that Alfieri was decidedly pro-Citroën when it came to the French company’s takeover. Elsewhere Sonnery also explains that Citroën was relatively hands-off in the management of its Italian acquisition. This blessed Maserati with a degree of engineering autonomy seldom experienced today, and Alfieri with a better budget than under previous Orsi ownership.

The Khamsin entered full production in 1974 replacing the 2+2 Indy and, indirectly, the two-seater Ghibli. Sadly, the Khamsin’s production run would be hampered by the fate of Maserati following Citroën’s financial collapse – thanks to model development expenditure and the 1973 oil crisis – and its subsequent acquisition by Peugeot. Even when it lived again under De Tomaso ownership, the Khamsin failed to realise its true potential before being superseded in 1982 by the Biturbo.

What makes this Khamsin, owned by David Jarvis since 2002 and today accompanied by his son Richard, arguably even ‘more Citroën’ is its three-speed automatic gearbox – one of an estimated 20 Khamsins to be so equipped. Richard feels the three-speed automatic suits the Khamsin’s GT credos and I have to agree. Slipping between ratios only seems to add to the Maserati’s sense of effortless ease and its optimistic modernity. I can’t help but recall the words of esteemed Car columnist LJK Setright when he wrote, ‘[People] still revere the hand-operated stepped-ratio gearbox, despite the fact that it is even more ancient than the screenwiper and very nearly as primitive. And still people choose to trample a clutch pedal, to heave a lever around, to waste time with every shift and waste energy through being too often in the wrong gear.’

And a pragmatist would possibly trade the involvement of a manual gearbox for the peace-of-mind associated with a three-speed automatic – in particular, the probability that this engine would not have been sadistically over-revved.

‘It would be natural to expect the marriage of three-speed auto to a V8 with motor sport DNA to be the embodiment of mismatched frustration – but no’

During the first few miles the high-geared steering (with just two turns lock to lock) feels too sharp and sensitive, rendering ‘normal’ inputs ham-fisted and so generating equally ham-fisted corrections. Until, that is, the penny drops and on fast-flowing roads, my inputs diminish – along with steering assistance – to the point that they are so subtle as to be barely visible. Goodbye lane wandering and hello easy, rapid progress. Again the sense of integrity – only ever savoured in original classics – adds to the composed serenity of driving this machine.

The same is true of the power brakes. After I’ve tested the seatbelt’s competence a few times, they become a matter of thinking about touching the pedal rather than consciously applying it. The pedal is so sensitive, with little discernible travel, it’s as if it senses my right foot’s approach and pops up to greet it. While the experience of using Citroën’s hydraulic braking system is unique, its performance is familiar to drivers of cars 20 years the Khamsin’s junior – it’s that impressive. It’s easy to see why Alfieri adopted this braking system, for it combines mighty deceleration with an unerring resistance to fade.

Remember, this car dates from the early supercar era where high speeds were achieved via improved engine output and low-drag, low downforce aerodynamics – which tested both the short- and long-term efficacy of conventional brake technology. Arguably perhaps, Alfieri’s enthusiasm for the hydraulic system did get a little carried away – for in addition to the brakes and steering it operated the clutch on manual Khamsins, pop-up headlamps and even the rapid driver’s seat height adjustment.

‘On anything broader than a B-road, the wide Khamsin shines through weaving asphalt non c’è problema’

The further I drive the Khamsin, the more at ease I feel, but there is a subtle juxtaposition. Compared to a Citroën this Franco-Italian hybrid (good though its ride quality is for a conventionally sprung GT) cannot match that of its pedigree Parisian cousins. Thus a confusing conflict arises between rump – which receives fine steel-sprung rather than sublimely cosseting oleopneumatic ride quality – and limbs that enjoy the usual high-assistance, sharp-response and slightly numb Citroën control surfaces.

It would be natural to expect the marriage of three-speed auto to 4930cc quad-cam, dry-sumped V8 with motor sport DNA to be the embodiment of mismatched frustration – but no. The V8 may have been a bit grey-templed come the Seventies, but this 320bhp unit is relaxed and linear with a good spread of torque. Producing a useful 354lb ft at 4000rpm, this translates to an asy 60mph cruise at 2500rpm. The auto’s performance may be down compared to the manual but it is still swift and the driver is by no means denied a mellow rendition of its rich, sonorous voice under acceleration.

The optimised weight distribution of the front-mid-engined layout and double-wishbone suspension contribute to its fine dynamic ability. Its quick-witted turn-in, crisply controlled body roll, neutral handling, surefooted stability and ride can be experienced without being sullied by tired clunky mechanicals. On anything broader than a generous B-road, though, the wide Khamsin shines through weaving asphalt non c’è problema.

In terms of width, it feels similar to a Jaguar XJ-S; in terms of entertainment it’s closer to a Jensen Interceptor – but as an enthusiast-targeting compromise the Khamsin takes some beating. Push an Interceptor too hard and you’ll wish for those fade-resisting Citroën brakes. Drive the XJ-S over racy cross-country roads and its casual manner is almost too disengaged, denying you the emotional interaction you get with the Maserati.

In fact, the only really lamentable thing about the Khamsin was the unfortunate timing of its birth amid unruly global events. Having the privilege to drive such a wonderful example of the breed, garnished with just a whisper of patina, really makes me appreciate Giulio Alfieri’s ultimate expression of what a front-engined Maserati GT should be.

Thanks to Denbies Wine Estate (denbies.co.uk) in the heart of Surrey, overlooking Box Hill. Denbies has more than 300 parking spaces on site and is the perfect assembly point for car owners. For group visits please contact events@denbievineyard.co.uk