With marque appeal on a high, more than a century of breeding and a staircase of affordability, now is the time to bag a Maserati

Photography: Charlie Magee/Rory Game

This feature was originally published in the December 2014 issue of Classic Cars_. Find out what's in the_ latest issue or check out our subscription offers

Maserati. There are perhaps two ways to define the marque. On the one hand it can be the thinking man’s Ferrari; packing the same kind of performance and style while being less, shall we say, obvious.

On the other, Maseratis are the perfect grown-up life choice for those schooled in the foibles of Alfa Romeo ownership but seeking a greater challenge. Just be aware, once you’ve been poked by the three-pointed stick, there seems to be no way back. All the owners I met and talked to are either in a long-term relationship with their Maserati, have owned a string of them, or indeed have kept acquiring more – five of them in one case.

Acquisition is less of an issue than it might be with Ferraris, because Maseratis are cheaper to buy. Don’t expect to run one on a shoestring, but where buying’s concerned, pretty much whatever your budget is, there’s a Maserati to suit.

Biturbo 228 (1982-94)

It would be easy to dismiss the Biturbo range – plenty have. Damned for their squint-from-the-right-angle resemblance to 3 Series Beemers, and blighted by early engine reliability issues and later rust problems, they have found few fans in the classic world. However, I know a few dealers who have taken advantage of this and bought them for peanuts to run until they dropped because they loved how the Biturbo drove and enjoyed the lavish cabins. There are two- and four-door versions, soft-top Spyders (which command the usual 50 per cent price premium), plus the super-sized 228 coupé launched in 1987, ten inches longer and six inches wider than earlier two-door Biturbos and targeted at the Mercedes luxury coupé market.

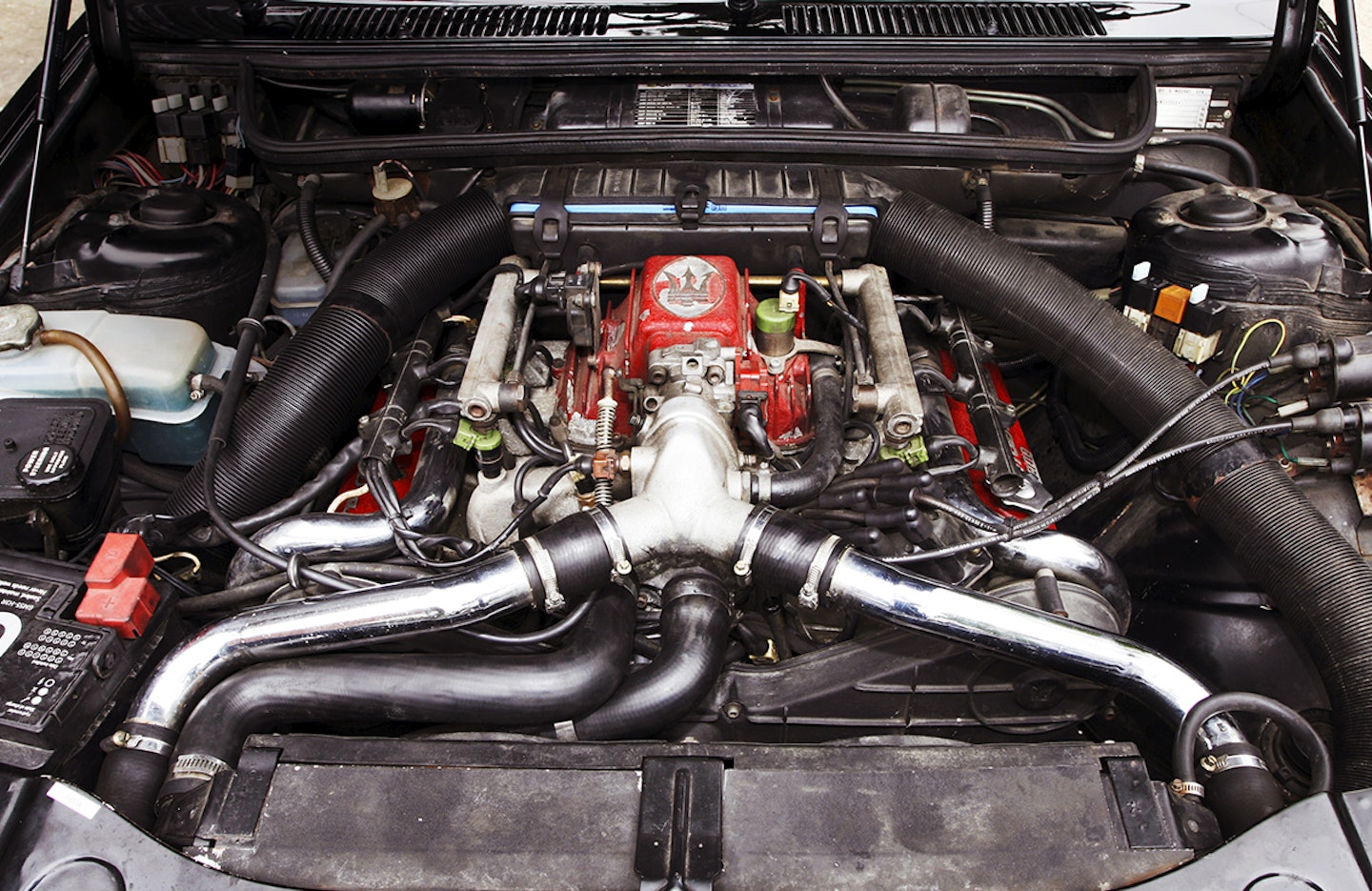

Alan Burns’ 228 here is one of just 469 built and packs a heady 255bhp from its 2.8-litre version of the twin-turbo V6 that gave the Biturbo range its name. That makes it a truly quick car, but as with many turbo installations, it’s one with a split personality. Anyone could jump in a 228 and drive it to the shops; it’s so docile, quiet and smooth that you could be in a Toyota or – dare I say it? – a BMW 318i, albeit one with every box ticked on the options list. I’m even moved to say that this car’s four-speed automatic box suits it. The engine only gets growly and raucous when you give the pedal a proper shove; then the 228 changes character and gathers speed at a rate completely at odds with its understated appearance. And the harder you push and the faster you go, the better this car feels – it’s a real street-sleeper. Yet it never seems unruly or dangerous – the tactile steering feels natural, with a good range of movement in the adjustable column. There’s more than enough grip from the tyres – which on the 228 are fatter at the back to counter criticism of earlier Biturbo tail-happiness – and the strong, progressive brakes inspire confidence. And I still don’t mind that it’s an auto.

I’m not overwhelmed by the styling; there’s a little too much rear overhang and the flanks might have been improved by tapering in a bit towards the rear, but other Biturbos are better resolved in this aspect so there’s plenty of choice. Just avoid the four-door models, which are the most prone to unfriendly Germanic comparison and will always struggle to be saleable, never mind collectable.

If you are now convinced there might be a Biturbo in your future, the greatest hurdle will be finding a good one. They are out there, but long-term low values mean that most won’t have received the care they need and many will have spent some time sat awaiting the funds or enthusiasm for repair work.

Main areas for concern are engines; tough and long-lived if cared for and only given synthetic oil, but likely to cost more than the car’s worth if they need rebuilding – £6000-plus. And check that everything electric works, particularly the cooling fans. If much is playing up, look at the fusebox – they often burn out and new ones cost £300. But find a Biturbo with the wad of bills to prove it’s been treated right and you will almost certainly be a classic bargain that provides ground floor entry to the wonderful world of Maserati.

Quattroporte III (1979-90)

From the imposing front grille and turbine-like design of the Campagnolo alloys to the hectares of leather and bird’s-eye maple inside, everything about this Quattroporte screams ‘expensive’. And these cars were – about 20 per cent more than a Merc 500 SEL back in the Eighties. Last of the hand-built Italian luxo-barges, QPIII’s were exclusive cars, built at the rate of no more than 200 a year. Styled by Giugiaro’s ItalDesign during his ‘folded paper’ period, the flat panels and sharp creases conspire to make an already big car look vast – this one’s fondly known in Maserati Club circles as the General Belgrano.

So it comes as a surprise to get behind the wheel and discover the QPIII’s willing and wieldy nature; it really doesn’t seem so big from in there and handles like a much smaller car. It even seems to enjoy being chucked about a bit and possesses a really sharp turn-in, though body roll and understeer soon join the party. Mostly, though, you’ll want to enjoy the smooth imperious feel of the car. It isn’t quite up to Rolls-Royce standards of waftiness, but only on poor road surfaces do you get noticeable levels of bump-thump. The QPIII doesn’t match Crewe build quality, though, particularly inside. Gaps are variable, stitched seams are wavy, the steering wheel could have come from a Lancia Beta. Perhaps it would be fairer to compare it to an Aston Martin ‘wedge’ Lagonda. Either way the big Maserati still has a powerful ambience and is a pleasant and spacious first class lounge of a place to travel in.

Acceleration from the big V8 is strong rather than spectacular, though it does have a lot of metal to shift. In that way, and thanks to the throbbing soundtrack too, there are echoes of Jensen Interceptor about it, reinforced by both cars sharing the same Chrysler Torqueflite autobox. The impression of invincibility comes undone when you ask it to stop. When you want and expect to feel bite from the brakes and some seat-belt massage on your shoulder, it isn’t there. Push hard and they get the job done eventually, but I found it unnerving enough to ask questions. The owner, Prag, has asked them too, but apparently Quattroporte brakes just are that way and there are no upgrades to be had either.

Finding a Quattroporte – at least in the UK – won’t be easy as they were never officially imported. You will also have to live with left-hand drive. When you do find one even the best shouldn’t cost much more than £10,000. Pay special attention to body condition as any new metal will have to be handmade, and external trim parts are unique to the Quattroporte. As with other Masers, electrics can be a weak link, and a poor interior would cost a small fortune to put right. Budget £2000 a year to look after one.

3200 GT (1998-01)

After decades in the GT second division, building cars that were fast but failed to tug on anyone’s heartstrings, it only took a glance past those distinctive boomerang LED tail lights to know that Maserati and stylist Giugiaro were back on form. The 3200 GT is one of those cars you know you want even before you hear about its supercar performance. Even better, despite those swoopy looks and 174mph potential it’s a full four-seater, adding a persuasive degree of practicality when you’re trying to justify buying one.

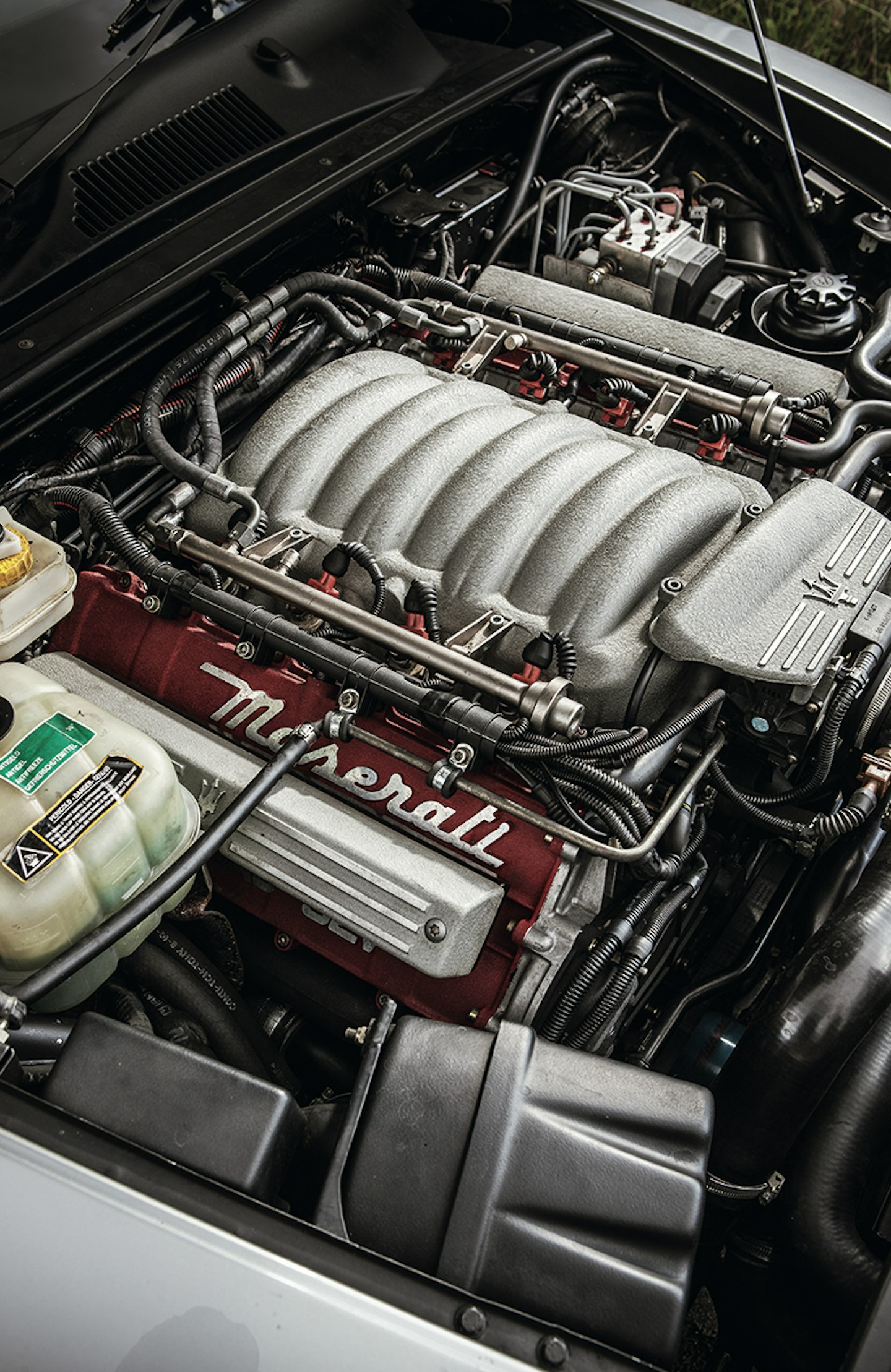

It’s hard to find fault from the driver’s seat either. The hair-trigger throttle pedal and eagerness to rev recalled memories of Peugeot 205 GTIs; the rush of vision-distorting acceleration put me more in mind of the last Star Trek movie I watched. At no point does the thrust from that twin-turbo V8 ever seem to let up, and the rest of the car’s dynamics are in full support. Steering is sharp and nicely weighted at all speeds, and those fat low profiles stick like chocolate on chinos – in the dry, at least. On wet roads it would be all too easy to unstick the back, so best to switch your right foot to tiptoe mode. The brakes are strong enough to almost pop your eyeballs out, and you can use that facility to the full knowing there’s ABS to bail you out. That’s all great fun, but if I can level any criticism it’s that the 3200 GT lacks the character of classic-era Maseratis. It’s very modern in feel, sound and looks. Which is great if that’s what you are after, but it’s hard to fully enjoy this car within the law.

So against all that background it’s sad to realise that this is currently the most flawed car here – at least in more desirable manual gearbox form. The story behind the ‘when not if’ engine failures of these is detailed in Brian Harris’s story (below), along with the fix he’s designed for it. The trouble is, that only works as part of an engine rebuild. In the words of Andy Heywood from McGrath Maserati, ‘There’s a cure, but it’s a £10,000 cure.’ And it’s not the 3200 GT’s only expensive flaw. The front lower ball-joints can wear out in as little as 20,000 miles, which is bad enough. But they are integral with the aluminium wishbones so have to be replaced as a whole unit at a cost of £1000. Each. So even if you do take Brian’s advice and buy a 3200 GT with an autobox, expect the occasional large bill – replacing the timing chain at 70,000 miles will add £900 to your service bill, and a set of the decent-quality tyres such performance demands will be £800. They’re not too bad otherwise, though: in 15 years Brian’s car – apart from the engine and wishbones – has only suffered the odd burned-out switch.

Tempting bargains are out there – a search turned up a 2001 auto with 52,000 miles and full history for £12,995. Only a Porsche 928 GTS or TVR Cerbera get close to providing similar performance for that money. Which would you rather have on your drive?

Merak (1972-83)

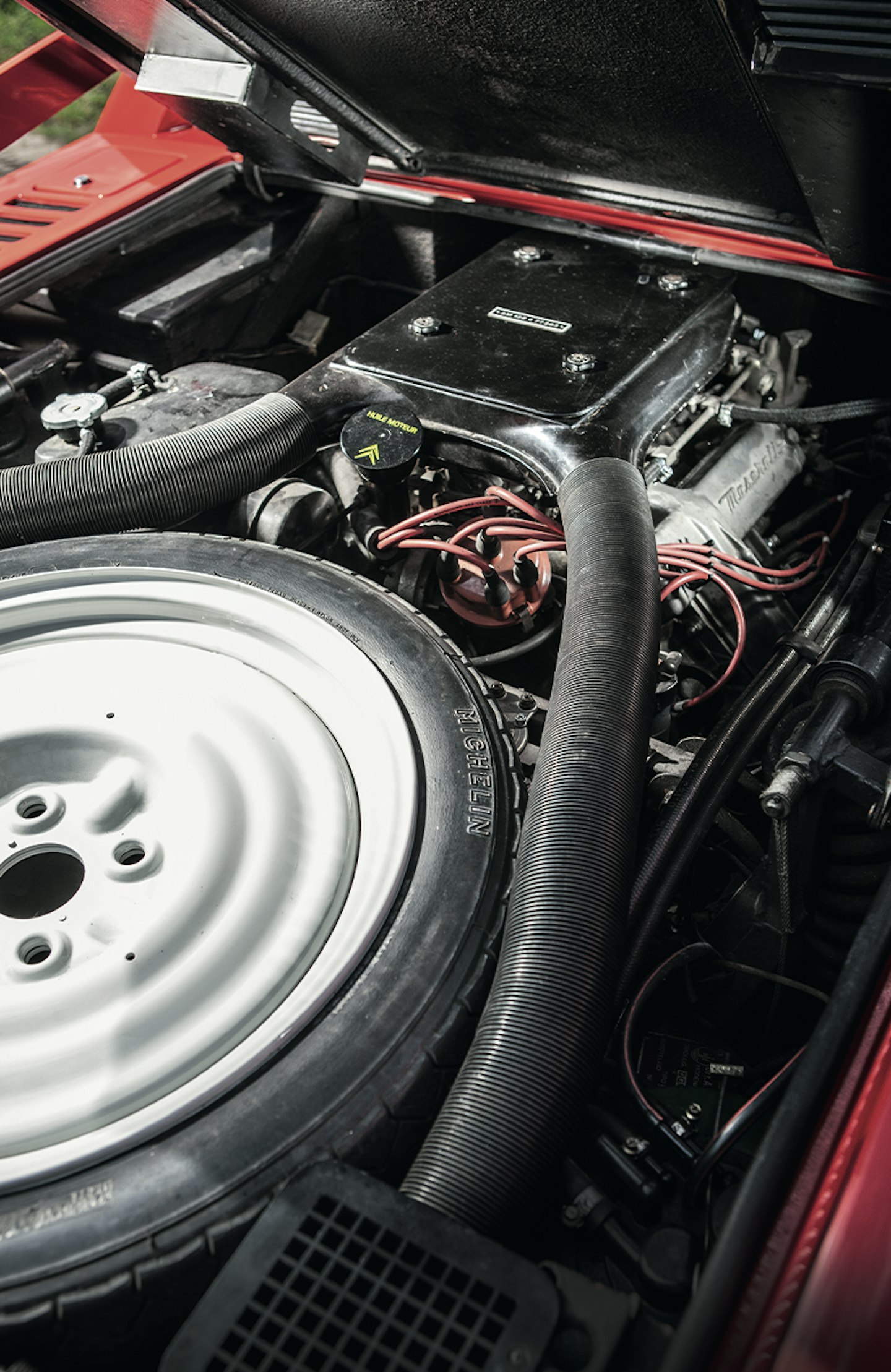

Borne out of Maserati’s seven-year fling with Citroën, the Merak was in effect a V6 version of the company’s first mid-engined car, the V8 Bora, even being largely the same bodily from the B-pillars forward. But the Merak outsold the Bora by better than three-to-one, helped by having similar performance to 70mph while using 25 per cent less fuel and costing £11,000 rather than £14,000.

The Merak’s three-litre engine was a bored-out version of the lightweight 2.7 used in the Citroën SM, providing excellent balance and 190bhp in early versions. The SM also loaned its gearbox and button-operated high-pressure braking system.

For 1976 the Merak was uprated to ‘SS’ spec, which meant an extra 30bhp, suspension tweaks, a taller final drive and less weight. Maserati claimed the slimming regime had shaved off 95kg; Motor magazine compared the weight with a previously tested Merak and made it just 15kg. Either was a step in the right direction.

Kevin Kemplen’s Merak is an SS, and a well-fettled example too, so we’re getting the full-on experience. The most brash of the cars here, it has all the subtlety of Tina Turner, and I’m not saying that’s a bad thing. If it matters, this is the only Maserati here that would look equally comfortable wearing a Ferrari badge.

I seem to be quite Italian-shaped, so wasn’t surprised that the driving position felt just right. The high centre console and angled middle portion of the dashboard help give the impression that the cockpit is wrapping itself around you, and the bank of stylishly pale-green-on-black gauges offer enough information to turn anyone in an Italian sports car neurotic.

With the advantage of a mid-engined layout, steering the Merak is a light and precise joy. But as ever there’s a payback and the distance from lever to box in a car from the infancy of mid-mounted engines has resulted in an extremely wide gate that takes a lot of getting used to. Third and fourth gears are where I expect first and second to be, but to find those I have to consciously lean to the left to slot the lever home. Yet reverse is practically in my lap. Adapt to that and you start to enjoy the Merak. It’s an aural delight, but unless I rev it out in each gear there’s always a bit more noise than go, not that it’s any slouch, and not that it minds being revved out in every gear…

Unless you’re double-chevron-trained there’s more adapting to be done for the brakes. The pedal might look normal but it operates in the way of those Citroën brake buttons and feels very wooden with short travel and not much initial bite. Push harder and suddenly Ihave way too much bite but still no feel. I’d hate to try it in the wet.

Meraks are plentiful, and now look very cheap at half the price of a Ferrari 308. But you need to check carefully for rot and the quality of past measures to deal with it. Gearboxes are tough, but feel for clutch slip. A rattly or smoky engine could land you with an £8000-£10,000 bill for a rebuild. Interiors are simple to retrim, but any broken or missing parts will have you searching the internet as little is available new. Citroën specialists can look after the brakes.

Indy (1969-75)

Unique here in being styled by Vignale rather than Giugiaro, the Indy looks almost too delicate a flower to be packing a 290bhp V8 punch, but punch it does. Autocar timed a 4.7 Indy like this (4.2 and 4.9-litre capacities were also available) at 7.3 seconds from 30-70mph in 1971. And then said the engine was still a bit tight and not giving its best. Exploring this one’s capabilities had me making noises like Homer Simpson at a doughnut stand. The Indy proved more refined, sounding like a Chevy fresh from finishing school.

Still belying it looks, everything about driving an Indy is a properly physical experience, as you’d expect and want from an old-school front-engined supercar. Every control has a similarly hefty feel to it, so you engage in driving it as a kind of whole-body workout, appreciating the solidly engineered feel of the pedals, steering and gear-change. Meaty is a word that springs to mind, but it’s all smoother, more tactile and less tiring than, say, a Daytona. This car doesn’t have the optional power steering, but that’s only of any real benefit when parking; at above 20mph the self-powered version is probably better as there’s nothing artificial to mask the excellent feedback to your fingertips. Being a pre-1973 Indy, this one also enjoys old-style and perfectly adequate brakes with plenty of bite. Later models got the Citroën system that I struggled with a little on the Merak, so you might find cognoscenti attaching some kind of premium to the purebred early Indys.

The turning circle’s appalling, but the handling is beautifully balanced and neutral. Adding more power mid-corner doesn’t unsettle the car, you just go round it quicker. It’s a similar story with mid-bend bumps, which fail to upset the equilibrium. All this in a car that’s a proper 2+2, with room in the back not just for kids but adults too, as long as they’re not tall ones. A velour dashtop both reduces reflections in the windscreen and provides a break from the acreage of black leather and vinyl that dominates the interior.

With 1136 built, roughly matching the total for Ghibli coupés, you have to class the Indy as a success, though they haven’t survived in the same numbers, almost certainly due to the usual elitist attitude to an extra pair of seats. That’s still reflected in their prices, which are only now threatening the £50k mark for the very best examples. The sad thing is that really top-notch Indys are hard to find. As is so often the case with ‘bridesmaid’ cars, they’ve never been worth enough for people to spend serious money on restoring them, unless it was out of love and with no concern for any return on their investment. So any example you look at needs to be checked over carefully and preferably by someone who knows these cars – there’s too much at stake to wing it with an Indy. For a start, if it needs an engine rebuild you’ll be looking at a £10,000 to £15,000 bill. Any metalwork for the body will need to be handmade, and many trim items – both inside and out – will require serious detective work to find or for one-off fabrication, which is never cheap. It might not put you off, but you really need advanced warning of what you are getting into.

Ghibli (1967-72)

We’ll make no bones about this: if you like Italian cars and can afford a Ghibli, you are doing yourself a disservice by not owning one. It’s that good, and in almost every respect, too – this is no one-trick pony. I did a back-to-back test with a Daytona some years ago; I’m a Ferrari fan but the Ghibli won. As a road car it matched everything the Daytona threw at it, and did so with class, style and maturity. Yet because of the badge on the nose the Ferrari cost nearly three times as much. It still does, despite Ghibli values nearly doubling since then, so they still look cheap in comparison. £100k will for now still buy you a good but not show-winning 4.7 coupé, though you’ll need another 20 per cent for a 4.9 in similar condition, and the very best examples command £150k. The Spyders are gloriously beautiful but their boat has already sailed – £100k doesn’t even buy you a project today.

Strikingly low – it’s under four feet tall – wide and sleek, the Ghibli is one of those rare cars that looks good from every angle; Giugiaro at his best, though for full appreciation it’s a shape that needs to be seen, like here, in a mid-tone metallic. People cannot help but stare at Brian Harris’s car, especially once it has announced its presence with a V8 burble that is more US than Italy; more restrained than brash. Unless you really blip the throttle, that is.

Even in its day the Ghibli was considered a bit old-tech with a leaf-sprung live axle. But with the advantage of experience, all that old technology has been honed to perfection: the chassis is lithe, supple and smooth-riding, yet extremely capable and predictable on the twisty stuff. It all adds to the suave, grown-up appeal of the Ghibli. Like the Indy, unpowered steering only calls for effort below 20mph, and is perfectly weighted above that.

Easy to place for corners, and with reassuringly strong, fade-free brakes and particularly blistering performance above 3000rpm, it’s a car you quickly find yourself bonding with and looking for excuses to drive again. Like all the controls the five-speed ZF gearbox’s shift is pleasantly physical but precise; an action matched by the long-travel clutch pedal, not heavy but with the kind of weighting that suggests strength and quality.

Buying a Ghibli is a different game to the other cars here as most have now been restored. That brings up questions like when, who by, and how well. A lot of older restoration work may not cut it in today’s market as buyers’ expectations have risen in recent years. One way to spot a good car is by its waistline crease. This should be sharply defined and flow flawlessly from front to rear.

Don’t be put off older restorations, but be realistic about their value and don’t overpay. It can take a lot of investment to bring an OK car up to modern standards, so they are often best left as-is and enjoyed. If that’s what you are looking for and can live with, then great. Otherwise pay the extra for a top example. You may also need to think in terms of left-hand drive to widen your choice as only a limited number of the 1280 Ghiblis built came to the UK and few of those were in 4.9-litre form.

Trident tested...

Six cars from the same manufacturer, yet only two of them were alike in character – the Ghibli and Indy, which raises the latter’s appeal when you compare prices. The others may be cheaper, yet none disappointed unless you count the brakes on the Quattroporte.

All had that sprinkling of magic dust that lets you know you’re driving something special and is what can lead you down the path of marque loyalty. I speak as someone who cannot imagine not owning an Alfa. Maseratis do the same thing but on a grander scale, with more cylinders, and the respective need for a deeper wallet.

That is the only catch with these cars; the entry price to ownership may be temptingly low, but it was clear from everyone we spoke to that the running costs are Prancing Horse-sized. If you can live with that knowledge, jump in and have a go. Despite the impression given by Ferrari owners and over-enthusiastic journalists, a Maserati is not some kind of second-best choice; they’re just different, and that bit more exclusive. That and an earful of V6 or V8 roar is enough to make any Maserati desirable.