Seeking a new path between bubblecars and ponderous saloons in the late Fifties and early Sixties, BMW built the 507 and 3200CS in a bid to break into the US market. A heady Italian road trip reveals what they created

Just five minutes have passed since I fired up this BMW 3200CS, yet I already feel compelled to drop all four of its pillarless windows. That’s partly because of the relentless midday heat pressing down over Lake Como intensifying through the massive glasshouse, but mainly so I can catch a better earful of the wonderful noise emerging from the exhaust.

A deep, distinctive marine-engine throb kicks gently across the cobblestones of the narrow single-lane roads out of Tavernola, rising in volume as stone walls built long before the invention of the internal combustion engine close in around it to create a bassy echo chamber. It’s a low note not unlike an American small-block, but with a metronomically regular, thumping tickover that speaks of multiple European carburettors rather than a gobbling four-barrel.

An oncoming truck driver catches sight of the sun glinting off the rounded ivory coachwork and respectfully pulls over to let us through – the 3200CS may carry the Bavarian propeller on its nose and the Hoffmeister Kink at the base of its slim-pillared rear three-quarter windows, but it looks more Italian than German.

There’s a good reason for this aural and visual culture clash. The engineering is Teutonic, but the bodywork is resolutely Torinese. Yet like so many flamboyant, musically loud Europeans, its intention was to sell in volume in America – where only a V8 would do.

So the story begins...

The 3200CS story began in 1960, when BMW marketing manager Helmut Werner Bonsch mooted the idea of persuading Pininfarina to rework its recently discontinued Lancia Flaminia Coupé body around a BMW 503 chassis and 3.2-litre V8 engine, creating an exclusive – and powerful – new flagship to replace the loss-leading 507 roadster that had been discontinued the previous year. BMW needed a car that could be produced more cost-effectively and use fewer bespoke parts, while at the same time retain the 507’s distinctively hand-built European aura.

The BMW board liked Bonsch’s idea, but employed Nuccio Bertone instead and designed a new chassis. Although Bertone’s design is fresh, there’s something about the proportions of the front end, with the plinth supporting the BMW ‘kidneys’ fouling the edges of the grille, suggesting a hasty afterthought at the clay model stage. It would look more comfortable playing host to a Lancia badge. The 3200CS looks much more elegant from the rear three-quarter view, with a subtle barrel-curve linking headlights to taillights.

It doesn’t feel particularly wieldy at low speeds. The driving position is typically Fifties, with the big squashy driver’s seat squab almost brushing the bottom of the steering wheel when no one’s sitting on it, and the big wheel itself compensating for heaviness. My legs are cranked at awkward, splayed angles, inadvertently adding to the car’s Italian flavour and making braking an awkward under-wheel shuffle that has the effect of lengthening braking distances.

Once on to the E35 autostrada for a three-hour jaunt, the 3200CS reveals itself as a sophisticated, refined highway cruiser.

Once the annoying high-speed buffeting has outweighed the threat of Italian summer heat, I wind the windows up again, and that heady, pulsating engine note dulls into the background. With the exception of some typical period irritations – a slight whiff of petrol and woefully bad cold-air ventilation – it feels modern and civilised at 70mph, solidly planted, square to the road and unflustered. Not unlike an Aston Martin DB5, in fact.

Braking is a cause for concern, however. At 1500kg it’s a heavy car, and although the long-travel dampers and soft springs make for excellent ride quality they struggle to keep the 3200CS’s mass in check, the body lurching forward under hard deceleration, front disc brakes eager to lock, tyres squealing. I adapt a cadence-braking technique, and I’m forced to use the outside of my right foot because of the steering wheel position. It’s uncomfortable, but essential to avoid losing control.

Too American for Europe, too European for America

The coupé’s composure completely falls apart on mountain roads. Any corner tighter than a moderate sweeper reveals the limitations of its American-style perimeter-frame chassis and live rear axle. The body leans so hard and severely that it feels as though the outside sill will scrape along the tarmac.

This tendency to sway about makes it difficult to work out where its centre of gravity is, and as the wildly yawing car hurls me across the flat leather seats there’s no scope for any mid-corner steering adjustment on the hefty wheel.

You just have to get all your braking sorted before pitching the car through the bend, choose your cornering line, stick to it and hang on. The weight blunts acceleration out of corners too, most markedly uphill.

Beautifully made though it is, I reluctantly conclude that the 3200CS is a bit of a dud. Initially you’re taken in by its dazzlingly handsome lines and thundering engine, and seduced by its high build quality, but its handling is too American for Europe. It’s also too European for America in that it’s just too much hard work. Perhaps it could be forgiven if it were a Ford Thunderbird competitor, but at $7875 in 1962 it was Cadillac Eldorado money, and those buyers wanted power-assisted, electrically adjusted effortlessness. So it comes as no surprise to discover that BMW sold only 603 of them in three years.

Rare delicacy

As evening falls in the hills above picturesque Castelnuovo Berardenga, in the Chianti wine-producing region east of Siena, I switch to the 507. It too failed in America, and even more spectacularly with a mere 252 being built in four years. Yet something in the way it surges up these mountain roads tells me I’ll enjoy the next stint on the legendary Futa Pass, part of the Mille Miglia route, a great deal more.

First impressions are good. Although it donated its massive steering wheel to the 3200CS, I’m sitting lower in better shaped sports seats, legs thrust straight out towards the pedals. The same snick-snicking, knitting needle-like gearlever that incessantly pinched my right knee in the coupé is a positive and unobtrusive reach forward in the 507. Odd to think that something so mechanically similar with so many identical parts feels so different. It’s a proper driver’s interior.

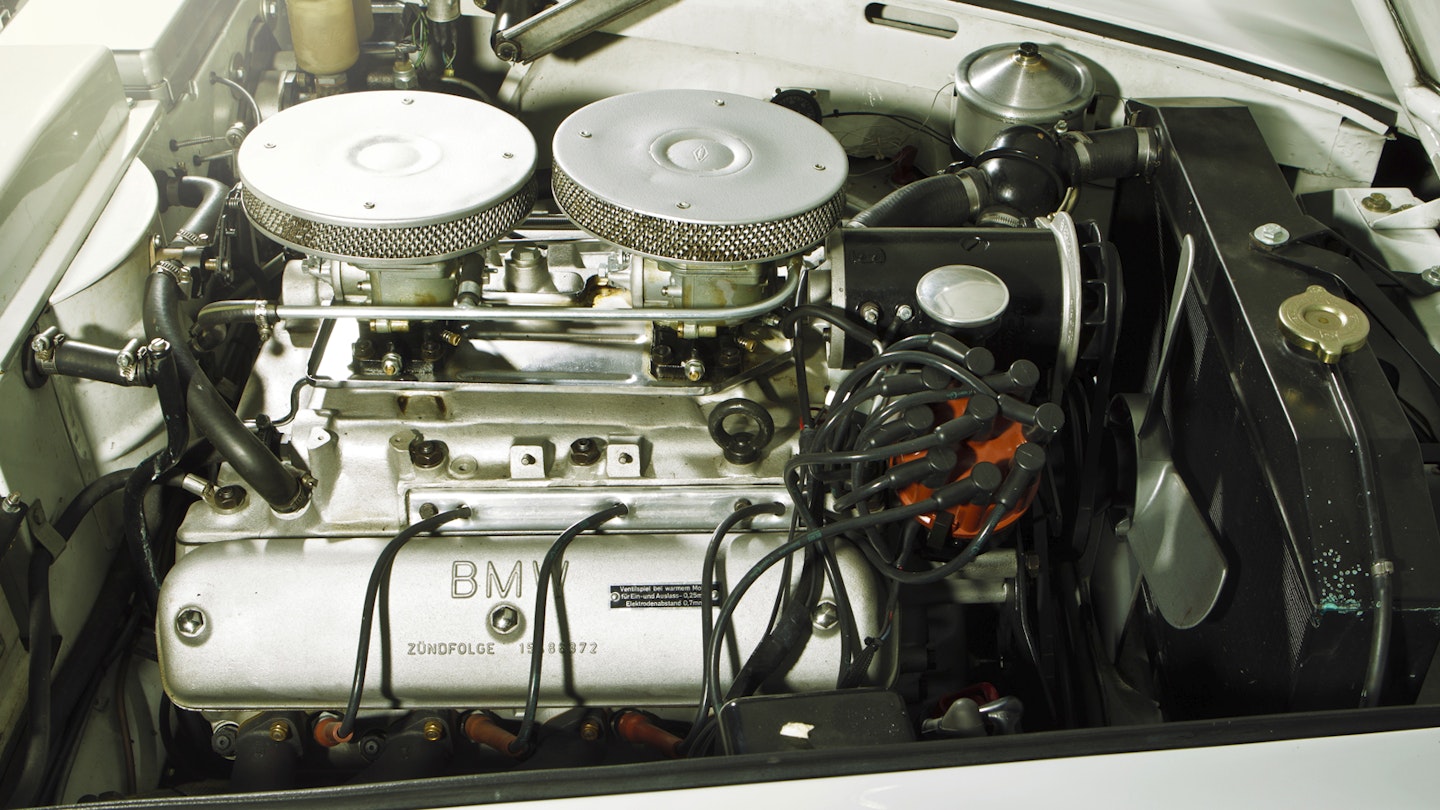

But the real treat comes when I press the tiny starter button mounted on the steering column. Freed from layers of saloon-style soundproofing, and channelled through sports exhausts, the 3168cc overhead-valve V8 explodes into life with loud, menacing fury. It’s like listening to a pair of millimetrically co-ordinated piledrivers taking turns to smash concrete slabs to smithereens – savage and visceral, yet with the precision of a true thoroughbred.

North of Florence on the SP8, the 507 reveals a character that’s more akin to a British roadster than anything German. Its aluminium body is light, but feels exposed with the low door sills hinting at MGA-style cutaways. Yet there’s no avoiding that rampaging V8, pushing the MG experience towards raucous Allard or even AC Cobra territory with every jab of the throttle.

I join the Futa Pass at Barberino di Mugello, and the 507 reveals ever-greater abilities. It may have a live rear axle, but it’s well-located with a Panhard rod, and the driving position puts the base of my spine just a few inches ahead of the rear wheels.

Quite the chariot

The effect feels like chariot racing as I sit well back and guide 150 charging horses ahead of me through each corner. Unlike so many front-V8-engined cars, where the centre of gravity feels as if it’s somewhere ahead of the gearlever, the 507 appears to pivot around the base of its seats, more like a Seventies monocoque with a transaxle gearbox than a separate-chassis Fifties roadster.

That’s thanks to thorough development – early prototypes based on cut-down 503 saloon chassis flexed far too much, so the reworked frame was reproduced in thicker-gauge steel, up to 2.5mm from 1.75mm.

With less weight to rein in, and double wishbones plus an anti-roll bar up front, the rack-and-pinion steering is precise, the wheel rim communicating potholes and ruts rather than the dull eddies detected through the top-heavy 3200CS.

Braking is also a much more positive experience. It’s the same front disc/rear drum set-up the 3200CS inherited, yet because it’s got less heft to cope with the car pulls up much more precisely, its poise unruffled into corners.

As I discovered last night, if you’re in the right gear at the apex when you hit the throttle, a kick of torque fires the car into the next straight with ease.

And that wonderful engine note, a meeting of American V8 aggression and European mid-capacity timbre, is ever-present and utterly intoxicating.

As well as being superior to its own successor, the 507 is also much better to drive than its arch-nemesis, the Mercedes-Benz 300 SL. The Mercedes appears more advanced, with its high-sided motorsport-derived chassis and fuel-injected engine, but on the road its swing-arm rear suspension and recirculating-ball steering make it feel alarmingly unstable compared to the 507 when you’re trying to make swift progress. The 507 is a much more precise car, even if its bigger, pushrod V8 is more than 60bhp down on the Mercedes’ silken straight-six.

Broken dreams

Sadly, such thorough engineering couldn’t save BMW’s dream (spurred on by charismatic US importer Max Hoffman) of bespoke hand-built BMWs rivalling British and Italian exotica in America. The car’s protracted birth – which saw it repeatedly re-engineered and expensively restyled – resulted in a masterpiece, but it nearly bankrupted the company.

With no money left to prove the 507 in motor sports despite Hans Stuck’s efforts in hill-climbing and Mauro Enriques in an unreliability-blighted 1957 Mille Miglia, it was too expensive and too obscure to make the impact BMW wanted, even though Elvis Presley bought one.

An emergency shareholders’ meeting on December 9, 1959 both brought the life of the 507 to a premature end and effectively sealed the fate of the 3200CS. Despite its expensively hand-finished Italian bodywork and convoluted production process, BMW just couldn’t afford to spend the money needed to develop and hone the low-volume coupé properly, and it was effectively rushed into production. No wonder it’s so disappointing to drive.

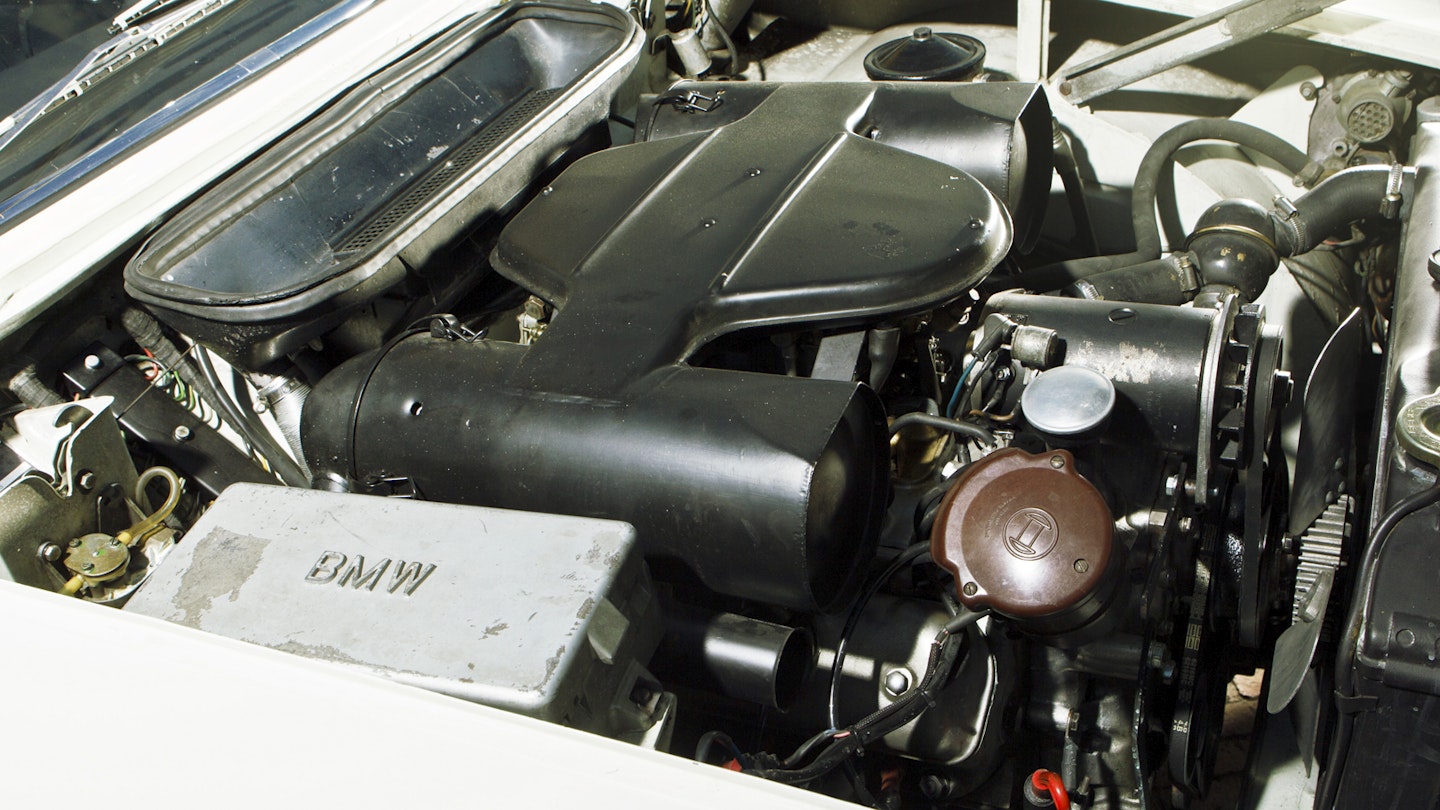

It’s ironic that BMW ultimately found salvation in the mass market. Although the Neue Klasse saloons and the coupés they spawned were products of post-war economic necessity, it would be thorough engineering that returned BMW to a position comparable to its pre-war greatness, ultimately resulting in the E9 coupés of 1969-75. With its coachwork hand-built by Karmann and underpinnings developed through touring-car racing, the E9 can perhaps be seen as the car the 3200CS wished it was. It wasn’t a long wait either – the 2800CS arrived just three years after its predecessor’s demise.

But despite the try-hard pastiche Z8 of 1999, the 507 has no true equal in BMW’s post-war era. Nor has the company managed to produce such an exquisite combination of design-house elegance, hand-crafted exclusivity and genuinely satisfying sporting poise.

So it’s hardly surprising that, 55 years after the 507’s demise, its price tag ensures it shares collection space with the kinds of car Max Hoffman wanted BMW to rival. The 507 may have had a hard life – but it also had the last laugh.

Thanks to: BMW Group Classic

This feature was originally published in the July 2015 issue of Classic Cars magazine. Discover more compelling features like it in our latest issue – buy a single copy, take out a print subscriptionortry the new Classic Cars Membership for just 99p!