This unique Mulliner-bodied Bentley 4¼-litre once belonged to legendary Bentley Boy Woolf Barnato. We hop aboard to explore its streamlined glamour

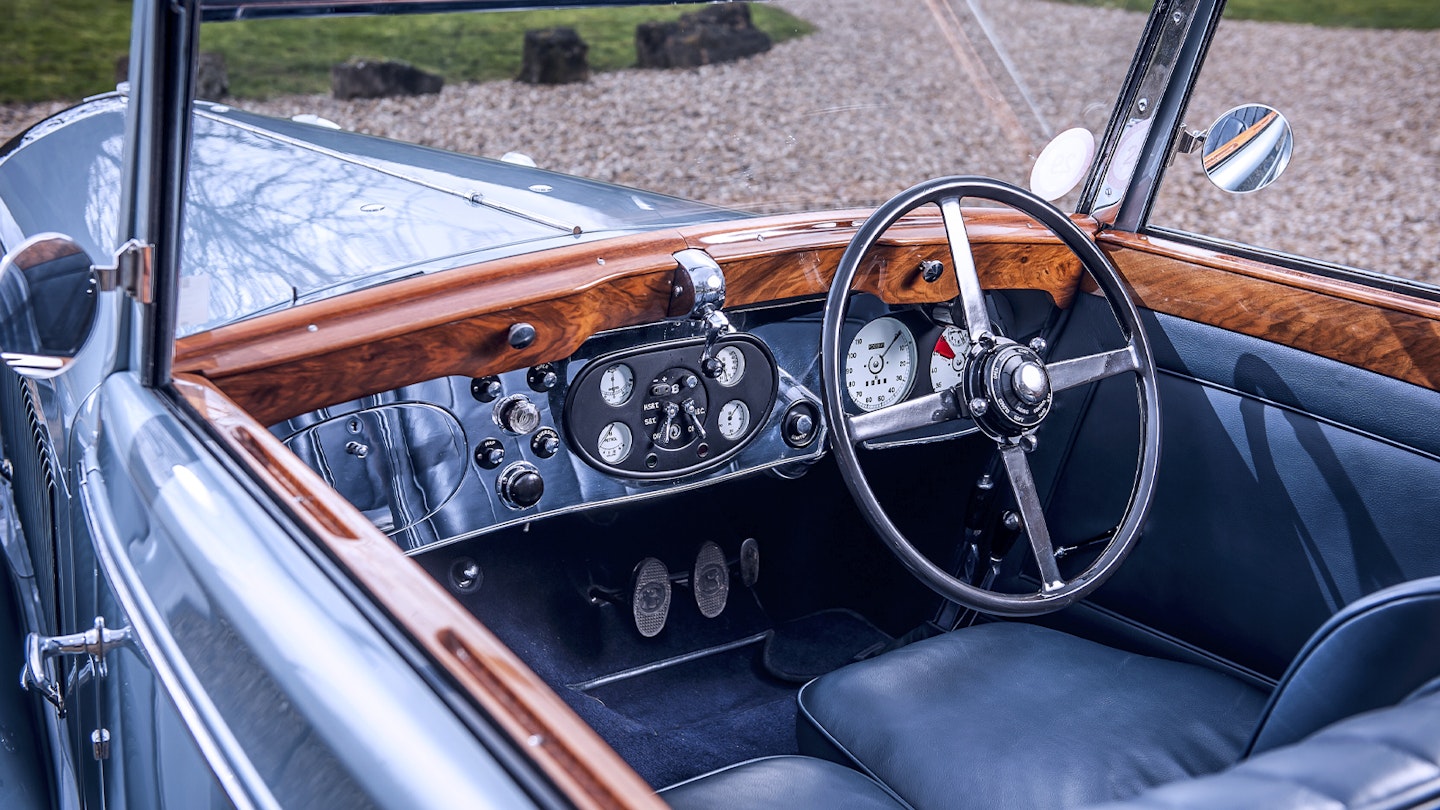

From a driver’s point of view, the early signs aren’t good. This svelte-looking car has very little space between the rim of the steering wheel and the seat squab, and the friction of wheel on thighs is adding weight to the already heavy steering. At parking speeds in this little Cotswold village, driving Woolf Barnato’s everyday car feels like arm-wrestling a surprisingly muscular old duchess.

Ah, but the road is opening up a bit. Down goes the accelerator, up comes a masculine, bassy exhaust note and off we go. And rather quickly, too, as low-down torque rapidly turns into mid-range power. Second gear goes in with a polite click, requiring only a cursory double-declutch, and then third and top gear surrender painlessly thanks to very effective synchromesh. Here’s a corner, and praise be – the steering has lightened into a tactile, well-weighted instrument that allows me to guide the big machine with a precision that isn’t common in cars of this period.

This Bentley is very highly geared thanks to a 3.64:1 rear axle ratio. This was fitted during the restoration to make the car more motorway-friendly, but also used in period if owners required more relaxation at speed than the standard 4.1:1 axle offered. Top gear is almost unnecessary on anything other than roads with the national speed limit sign, though the torque is there to drop it into top at much lower speeds if I wish. Performance is a world away from the Rolls-Royce 25/30, to which this Bentley is closely related.

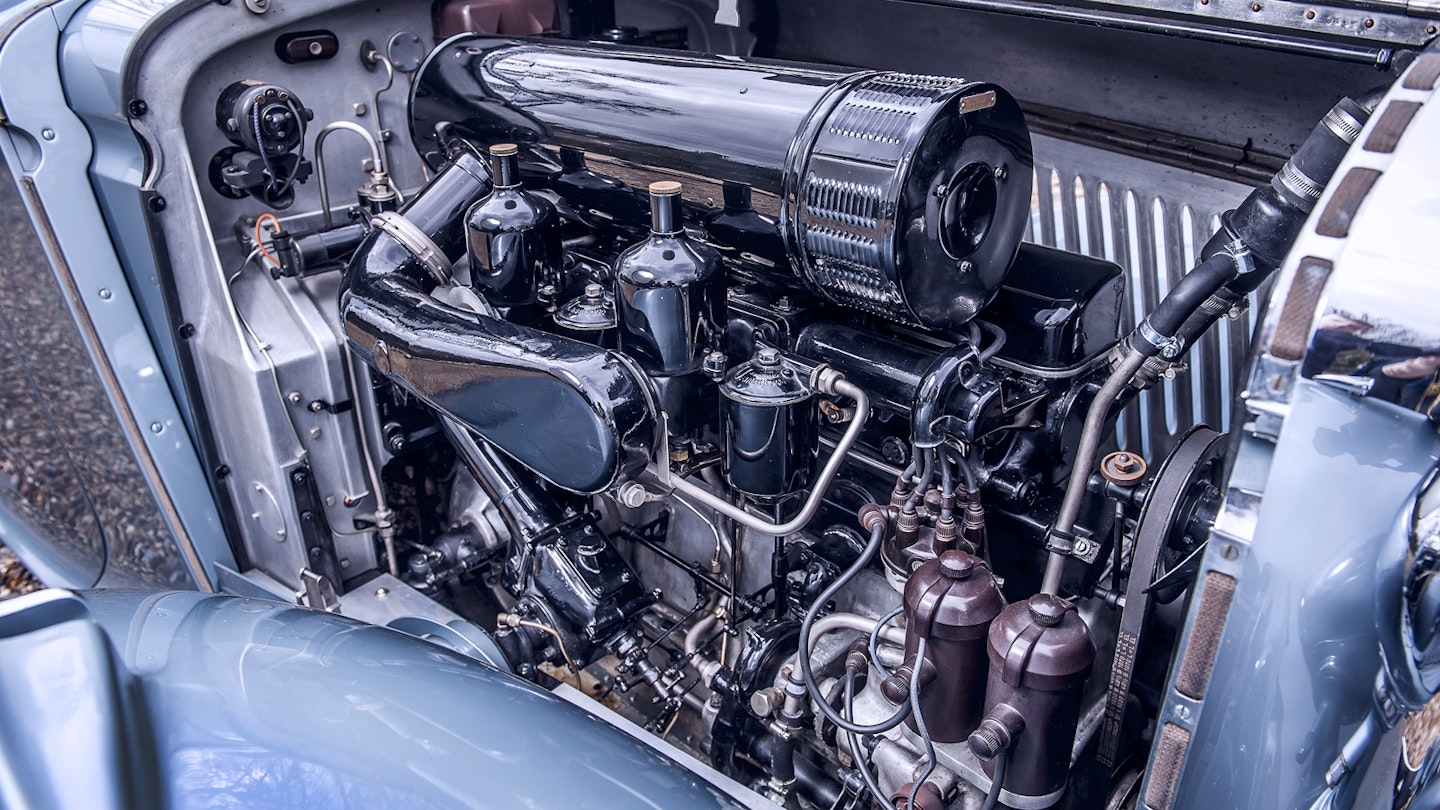

‘Derby’ Bentley owners often emphasise how different their cars are from their Rolls-Royce stablemates. The Bentley’s chassis is lower, shorter and a little lighter than the Rolls-Royce, but the running gear, braking and transmission are largely shared and feel very similar in use. It’s the engine that makes the big difference: add a crossflow cylinder head, a more sporting camshaft and twin SU carburettors and you turn the somewhat breathless Rolls-Royce into the ‘Silent Sports Car’, as Bentley’s promotional materials famously put it.

This car benefits from pistons that raise the compression ratio from 6.8:1 to a very post-war 8.5:1. Hardened valve seats in an aluminium cylinder head allow carefree use of modern fuel and that increased compression ratio seems to make the most of our modern 95-octane rating. The way this car changes character from suave cruiser to almost caddish sporting machine when I prod the accelerator suggests that rather more than the original 125bhp is available to my right foot.

The brakes are tremendous and freshly adjusted, betraying none of the low-speed delay that can often be sensed with Rolls-Royce’s mechanical servo. The car’s relatively low and dashing lines leave the driver more exposed than in a contemporary Rolls and there’s no heater, so I sit tight and think of England until I start to turn blue, and then reach for the roof. Up comes that elegant cover panel and with help from a passenger, the coupé’s handsome folding head is erected and the windows wound up. It’s undoubtedly luxurious for a drophead – wonderfully snug and windproof, so driver and passengers can start to enjoy some heat soak from the engine.

Former Bentley Motors owner Woolf Barnato could afford more or less any luxury he wished for, which makes the early history of this car – or rather its bodywork – a little puzzling. The body was first ordered by the Barnatos on chassis B2DG, a 3½-litre model, in November 1934. It was then moved on to chassis B121GP, a new 4¼-litre model, in June 1936. If they wanted a newer, faster car when the 4¼ was announced, why not have a new body to go with it?

All-steel bodies were still in the future for Bentley; Park Ward’s first steel saloon was patented and built in 1936. While it was stiff, quiet and rattle-free, the idea and the technology didn’t become widespread until post-war production. Traditional ash-framed, metal-panelled bodies could be rather weak, but if you got a good one it wasn’t at all uncommon to move it to a newer chassis when it was time to upgrade the car.

There’s an issue of time as well. Creating a new body would mean a wait of weeks or months after ordering the chassis from Jack Barclay, while swapping the old one from B2DG to B121GP would be the work of a few days for the skilled artisans at HJ Mulliner. Intriguingly, there is also the influence of Jacqueline Claridge Barnato to consider. She was an American heiress and Barnato’s second wife; they were married in 1933 when he was 38 years old and she was 25.

The order sheet for B2DG was originally in the name of Capt. Woolf Barnato, but ‘Capt’ is crossed out and replaced with ‘Mrs’. Likewise, the original coachbuilder’s name, Thrupp and Maberly, is crossed out and replaced with HJ Mulliner.

Then, when Woolf Barnato ordered B121GP, it appears that he initially did so with a Vanden Plas pillarless saloon coupé body, but again the coachbuilder’s name was crossed out and replaced with that of HJ Mulliner. We can’t conclusively be sure, but maybe Jacqueline suggested the swap.

It’s a tempting idea that follows the logic from that first change of name on the original order sheet. Perhaps Woolf Barnato started off by ordering a Thrupp and Maberly coupé, but following a rush of enthusiasm from his young wife over a glamorous HJ Mulliner drophead, he turned the order over to Jacqueline. When he was in the mood to upgrade the car to the newer, more powerful 4¼-litre specification, it’s possible that Jacqueline once again intervened, reluctant to let go of the sleek bodywork she’d enjoyed using over the previous year and a half.

Where did this enthusiasm for the streamlined, concealed-roof look come from? If you examine what was going on at that time, you find it was all around. This design by HJ Mulliner was undoubtedly advanced, but it was far from unique: indeed, one glance at a review of the 1934 Olympia show reveals it was part of a wave of similar designs. The Motor of October 10 1934 – just five weeks before the Barnatos placed their order – headlined its piece ‘The Streamline Tendency at Olympia’, calling it ‘the outstanding feature of the show’. Several cars were shown, either as photographs or illustrations, taking in a variety of approaches. The most radical streamlining was demonstrated by Chrysler’s Airflow and some remarkably similar British equivalents from the London coachbuilder Windover. The first was on a Daimler straight-eight chassis and the second on a Singer, in the form of its 11hp Airstream saloon, which entered production that year.

Also featured were some more conventionally attractive designs from Park Ward, which exhibited almost teardrop-tailed four-door saloons on the Bentley and Rolls-Royce Phantom II chassis, and Thrupp and Maberly’s even more rakish, rear-wheel spatted Bentley saloon. And below that, a very familiar HJ Mulliner drophead.

The show car was chassis B22BN, one of a total of four built with the body design the Barnatos (or Jacqueline, anyway) ended up choosing. The Motor was complimentary about all the cars it featured, observing that ‘coachwork by Park Ward, Thrupp and Maberly and HJ Mulliner on Bentleys and the Park Ward Rolls-Royce preserve the conventional radiator and bonnet, yet in every other respect are developed on lines of full aerodynamic efficiency.’

The writer was very much of the opinion that this was more than a styling craze. ‘It is useless to suggest that it is a passing phase. Without retrogressing there is no alternative.’

This reminds us just how forward-looking the mood was at the time, as the design and performance of many modes of transport moved on in significant leaps. Look at other examples that appeared in Britain in the early Thirties: the de Havilland Dragon and Dragon Rapide were genuinely streamlined short-haul airliners that helped turn air travel from a dangerous stunt to a near-normal mode of transport, at least for the rich. The year after the Dragon Rapide first flew, the LNER’s A4-class locomotive emerged, one of which, Mallard, eventually became the world’s fastest steam locomotive. The point is not only the performance, but also the look – both examples differed wildly from what had gone before.

The Motor may have considered streamlining a serious advance in automotive efficiency, but by measurable standards, these supposedly slippery car bodies with their conventional Thirties radiators and headlamps were still far from aerodynamic. Nonetheless, The Motor identified a genuine advantage. ‘…There is the absence of the following vacuum which, with the normal upright type of rear panel, tends to sweep in dust and mud, making the back of the car extremely dirty and unsightly.

‘With the modern streamlined tail, however, a car can be driven fast in bad weather for a whole day without requiring any more than a simple rub-down.’

We have occasional blasts of chilly rain with which to test this theory today, and it holds true – the car remains pretty clean, despite its relatively low-slung stance. While we’re examining the tail end of the car it’s obvious what a coherent piece of design it is. The large spats work beautifully with the concealed spare inside the bootlid and the noticeable taper in width, as well as the obvious slope down in height.

Further forward, I notice the mirror on the driver’s front wing, faired into a delightful fluted shape behind a little pod-like sidelight that rather makes a nonsense of the effort expended on streamlining the mirror. There are numerous features that contribute to the aesthetics without helping the air slither past, like the back-angled louvres in the bonnet sides, the crease in the crest of the front wings and the chrome side spear that emphasises the falling waistline.

Just here is the hidden roof. It disappears beneath a folding cover, which is locked down with neat catches that occasionally misbehave if I’m not careful enough in stowing everything, but in the ten years since this car was restored it’s seen much use, so a little slackening of the hand-made structure is natural.

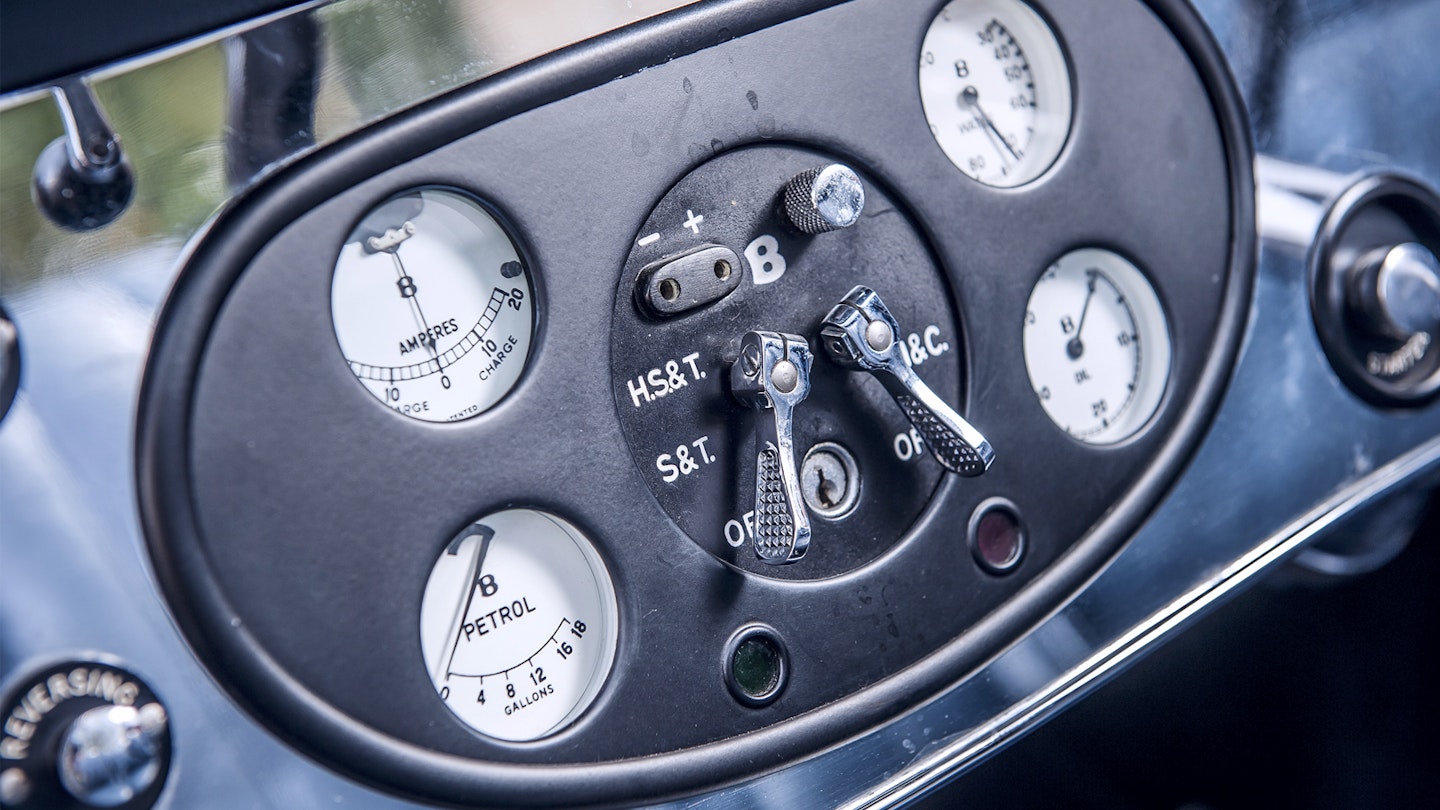

Elsewhere, it’s difficult to age the restoration at all. The paint is still deep, even and lustrous and the leather unmarked, if perhaps a little mellowed. The interior isn’t much different from any other Derby Bentley, excepting Barnato’s white-faced dials, specified on the order sheet. Climb out again and regard a subtly clever feature much lower down – there is a distinct turned-out bottom edge in the door and rear wing. This was mentioned in a contemporary account by The Automobile Engineer of November 1, 1934. ‘In this example, running boards are absent, but the lower surfaces of the side panels are outswept and tend to avoid the unfinished appearance which is often given when an orthodox turn-under is used on a body without running boards.’

For a stylist to conceive the idea is one thing, but for that to be made successfully is another. The typical flow of work in a coachbuilding company of the time ran as follows, though with variations from firm to firm.

First, the shape was created on the drawing board, and when ready it would be turned into a colour wash for approval by the client. After approval, accurate detailed drawings were made. These were then scaled up to full-sized working drawings from which the frame was constructed by the body shop. Workmen often operated in gangs and the foremen would negotiate prices for each bit of work in advance. It’s important to recognise that these craftsmen were artists too – they had to interpret a drawing and determine how it would work.

The outswept lower edge would re-appear after the war on Bentley MkVI dropheads by various different coachbuilders. It’s one of the features of this car that could be called influential, but it’s important to recognise that B2DG, as it then was, didn’t shake the automotive world to its foundations. What makes it a success in styling terms is the balance it strikes between streamlined shapes and the recognisable, conventional good looks you have a right to expect from a Derby Bentley.

It looks a generation younger than HJ Mulliner’s handsome three-position drophead coupés from the same year, and more dramatic than the firm’s next stab at a concealed drophead coupé. It would have turned heads effortlessly, yet offered nothing to shock or challenge the taste of a well-bred owner.

It seems Mrs Barnato kept using the car until either just before or just after the war, which was quite a lengthy ownership for a millionaire and his wife in such a forward-looking time. Does it still have the power to excite? Certainly, thanks both to its increased potency as a driving machine but also to the thrill that a really well-executed piece of streamlined styling still creates. It wasn’t an eccentricity to keep this bodywork and move it to another chassis, it was the only sensible thing to do with a damn fine bit of work.

Thanks to: Fiennes Restoration Ltd (fiennes.co.uk), Georg Ellbogen, William Morrison, WO Bentley Memorial Foundation (wobmf.co.uk), the Rolls-Royce Enthusiasts’ Club (rrec.org.uk).